“A House Is Not A Home If There’s No One There” Bed Stuy’s Demolished Dangler Mansion

Historic preservation is important in all communities. Here's why.

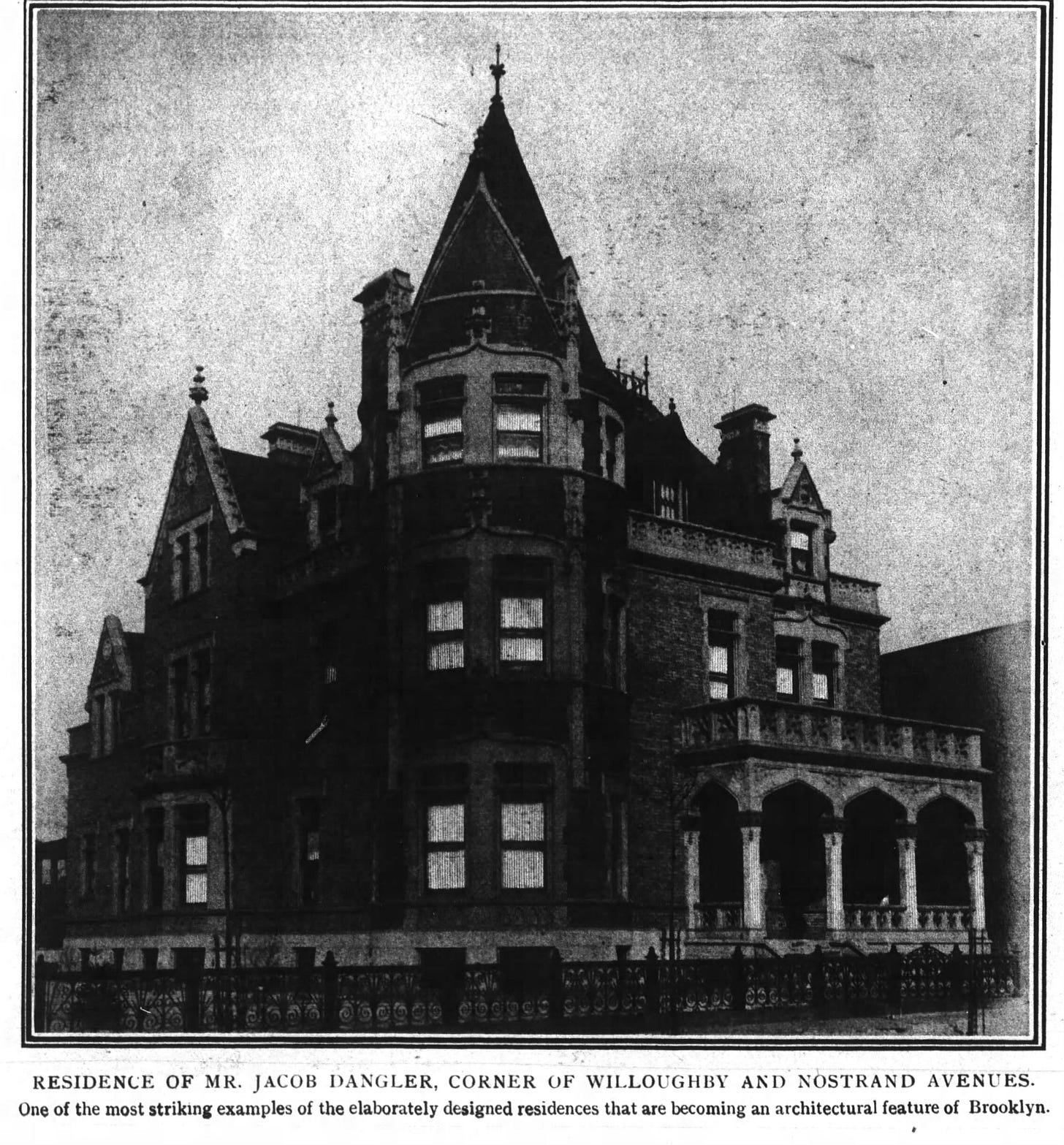

(Brooklyn Life Magazine, February 23, 1901)

The talk de jour in my email and on my Facebook feed this week was almost entirely taken up by the news, photographs and videos of the destruction of a Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn house called the Jacob Dangler mansion. Personally, I’m still furious that the building was destroyed, and I’ll get to that in a minute. But first I want to tell you about the house and the family that first called it home.

Jacob Dangler was born in Alsace-Lorraine in 1851, the son of farmers. At that time, this border state belonged to Germany. Dangler came to the United States, landing in Brooklyn at seventeen, living with an aunt. Like many German immigrants, he began work in the grocery business. After a year, he took a job with Andrew Harman, owner of a provisions store in Williamsburg.

Young Jacob discovered he liked provisions, which are what we today call deli meats and cold cuts. He worked for Harman for ten years, learning the meat processing business. He got married, bought a house in Williamsburg, and opened his own meat and provisions establishment. Mrs. Dangler helped him in the store and was the bookkeeper for his business. The three Dangler sons grew up working in the store, as well.

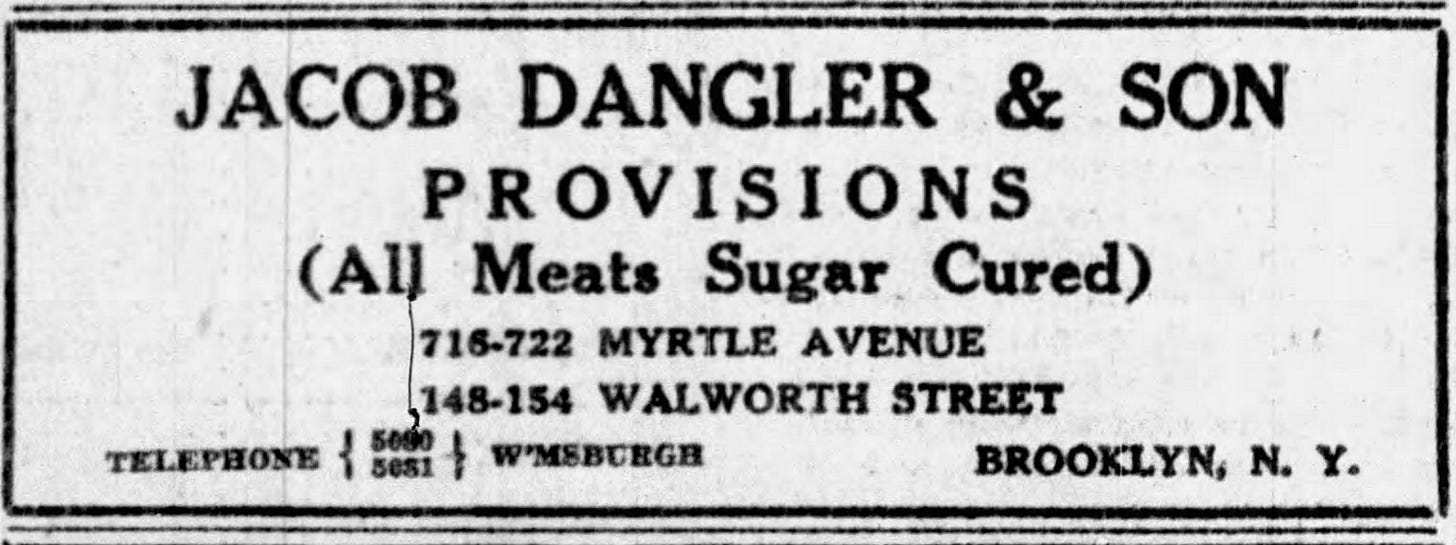

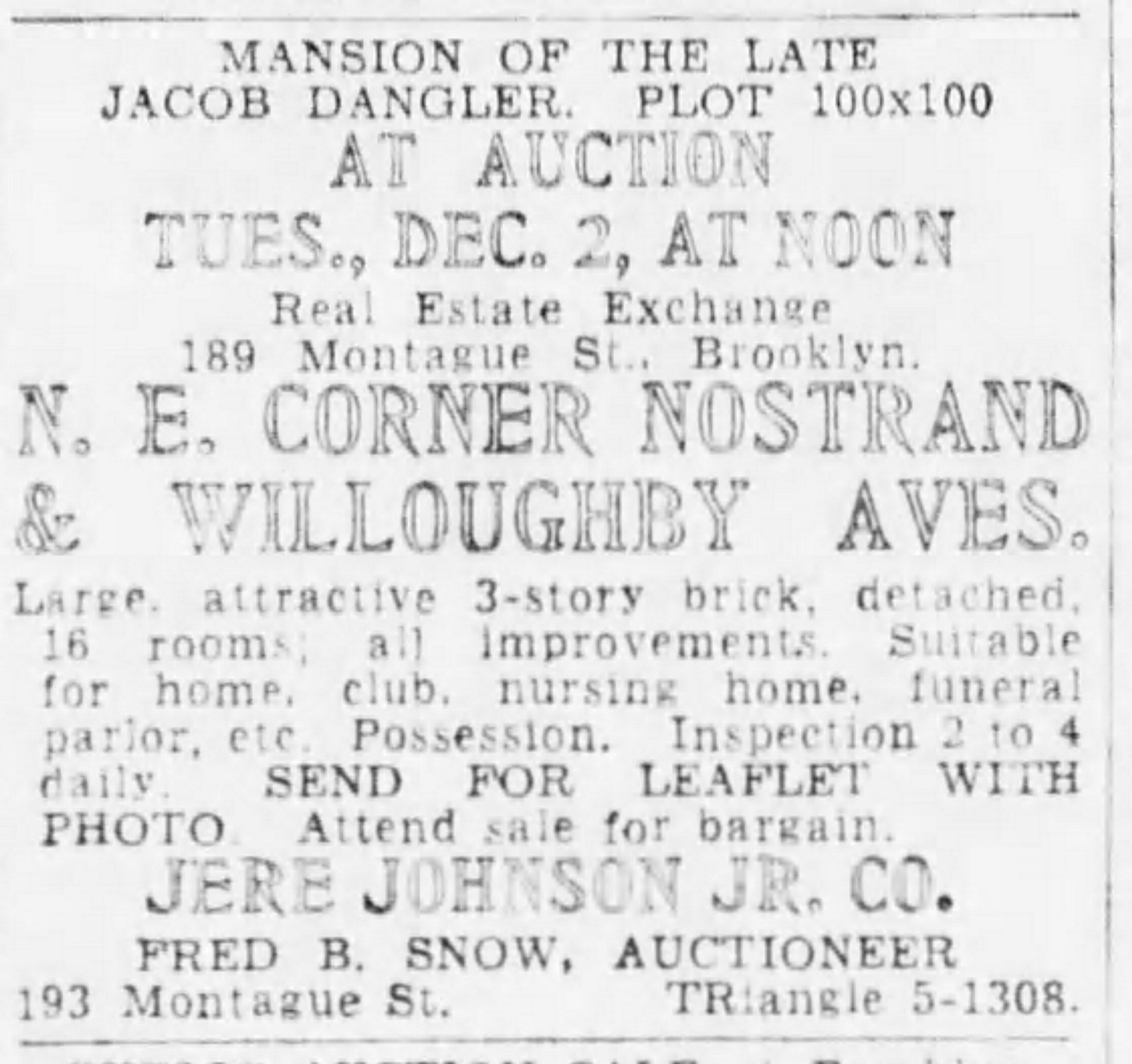

(Ad in the Brooklyn Eagle, 1930)

In 1884, his business moved to a larger facility on Myrtle Avenue. In time, he greatly expanded this facility, using Brooklyn’s most prolific and talented German American architect, Theobald Engelhardt, to design additions, garages and other changes to his property.

By the turn of the 20th century, Jacob Dangler’s business had grown to the extent that he was a wealthy man. Like many rich men, he had been approached to join the board of at least one bank, and he was also a real estate investor and landlord, with many residential properties in the area that he both rented out or bought and flipped. But he was still living in a rather non-descript home on Myrtle Avenue. It was time for new digs worthy of his status. He commissioned a mansion for a piece of property he bought on the corner of Willoughby and Nostrand Avenues. He once more turned to Theobald Engelhardt as his architect.

(Photo: Suzanne Spellen)

The block the house sits on is lined on both sides with Neo-Grec brownstones built in the mid to late 1870s. It was a nice, middle-class Brooklyn row, but not the location where one would think a fine mansion would be. A few blocks east of here, further up Willoughby were the large houses of other successful German businessmen, but down this way, Dangler’s house stood alone in its splendor.

The style of the house was unique, a French Gothic design in golden brick with white limestone trim. Perhaps Dangler wanted a building that reminded him of home, an area that was pulled between Germany and France with great regularity. When his father had been born in Alsace-Lorraine, it was French. By the time he came along, it was in German hands. Today, it is once again French.

Dangler was also a dedicated church-goer, and a leading member of St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, on the corner of Bedford and DeKalb Avenues. Jacob had been a member for many years and was president of the board of trustees there.

The very Gothic elements of the house’s design could also reflect his religious side. The exterior abounds with trefoils, quatrefoils and other “churchy” elements so familiar to Gothic architecture. But then, I could just be over-thinking it. Perhaps Jacob just wanted a French castle on his little corner of the universe, where he could be king. The house was completed in 1901 and was featured in Brooklyn Life, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper’s society magazine.

Unlike many other wealthy people, the Dangler’s were very low profile. One would expect, with a fine house like this, that there would be lots of parties, soirees and society events, showing off their wealth, but the Dangler’s were not flashy people.

In 1903, two of the Dangler brothers got married in a double ceremony. George married Louise Humbert, a young woman who was employed as the housekeeper at the Dangler home. Emily Lohmeyer, the bride of Albert, met him while working as a cashier in Dangler’s store. The third brother, Henry, married Emma Julia Heischmann, the daughter of Rev. Dr. John Heischmann, the long-time rector of St. Peter’s Lutheran Church.

(Photo: Brooklyn Eagle newspaper, 1931)

Jacob had a very long life, filled by a busy career and a long association with community and church. His company, which he ran with his son George, grew over the years. His meat products, especially his bologna, were highly regarded and sold well to the growing number of delicatessens and food markets, The eating habits of Americans changed greatly in the 20th century. Sandwiches became an American necessity for working folks and school children alike.

In 1911, Albert left his father’s business and set up his own shop in the Sunset Park area. He was not as successful as his father, but he did well. Unfortunately, he was never in great health, and died well before the other members of the family. His mother, Josephine, died in 1929, after a long illness. Jacob died in 1939, at the age of 87. Up until his death, he carried on his usual routine, getting up at 5 in the morning, and walking over to his business to conduct a full day’s work.

He joined his wife and son in Green-wood Cemetery. He left behind his other two sons, their wives, eight grandchildren and one great-grandchild. The house went to George and his wife, who had been living there since they had married. Henry was a doctor and lived in suburban Flatbush. In 1941, the house was put on the market. A large ad was placed in the papers, touting the house as an ideal location for a home, club, nursing home, school or funeral parlor.

(Ad in the Brooklyn Eagle, 1941)

26 years later, in 1967, the building was purchased by the Oriental Grand Chapter of the Eastern Star, a masonic organization founded in 1850 for women. Orders of the Eastern Star are usually founded in conjunction with a male Masonic counterpart. The Order has owned the house ever since. This was always an African American Eastern Star chapter. Over the years, the house underwent many changes. Walls were taken down and the house expanded into large rooms for meetings and events. An extension was added in the back to allow for even more banquet and special event space.

(Photo: Susan DeVries for Brownstoner)

The Post-Dangler Years

I wrote a much more detailed version of this story for Brownstoner.com in 2014. Up until that time, and from that time until this year, it was the only article written about the house. It remained a curiosity for many, a big old white elephant mansion that happened to be across the street from the Bed Stuy Home Depot, which had opened only a few years before. But it was much more than that.

This block is in the northern part of Bedford Stuyvesant. Way back in the 19th century, this was the western end of the neighborhood called “The Eastern District,” which consisted of this part of today’s Bedford Stuyvesant eastward, over to and including most of Bushwick. The District was home to a large German immigrant population, a group that began settling in the area in the late 1840s, while the German city-states were engaged in civil war.

By the time of our Civil War, this was home to a successful community of German-Americans, some of whom became very wealthy as brewers, wholesale grocers, manufacturers and bankers. It was not a coincidence that Jacob Dangler was in this neighborhood. Architect Theobald Engelhardt was the most prolific architect in the ED, with commercial, sacred and residential buildings to his credit. His work is important to the architectural history and fabric of Brooklyn.

By World War I, neighborhood demographics began to change. The German Protestants began to leave, replaced by German and Eastern European Jews, and Irish and Italian immigrants, many of whom worked in nearby factories and at the Navy Yard. After World War II, more and more African Americans called the neighborhood home.

By then, the entire neighborhood had been redlined by the government, which declared the neighborhood (and all Central Brooklyn, Williamsburg and Bushwick) to be a poor investment, with old building stock, immigrants and worst of all, black people. No major bank would fund a home mortgage.

Despite the hardships, African American buyers did manage, and even through the closing of the Navy Yard and the factories, drugs and the urban chaos of the latter part of the century, they settled on streets like Willoughby Avenue and its neighbors and created a village. The Dangler house was part of that village. It was the Town Hall.

The ladies of the Eastern Star were very generous with their new headquarters. The chapter had a sizable membership dedicated to public service, providing mutual care for their membership, and mentoring to young women and the children of the neighborhood. Their headquarters was a welcoming gathering space.

The Dangler mansion was used for Masonic meetings, and leased out for neighborhood events – wedding receptions, showers, graduation and birthday parties, and meetings for other organizations and non-profits. The local Boy Scout troop held their meetings here, so did the Willoughby Avenue Block Association. For over 55 years, this was “the Castle,” to the children of the block, with turrets and towers, a magnificent and impressive structure, even as it aged. The Dangler family was long forgotten, as often happens, but the Castle remained.

The new century brought new people to the neighborhood and new attention to the neighborhood. Bedford Stuyvesant, long feared and shunned as a crime ridden, rundown and dangerous ghetto, was suddenly HOT! Priced out of nearby gentrifying Clinton Hill, Bushwick and Williamsburg, young renters, most of them white, were finding affordable apartments in Bedford Stuyvesant. They weren’t afraid of living there, they reveled in the “edginess” and the cool of it all. Businesses like cafes and coffee bars were following them eastward, subway stop by subway stop.

Real estate developers had already begun to take notice. Compared to other parts of Brownstone Brooklyn, the properties here were cheap, even cheaper than in other parts of Bedford Stuyvesant. In the last 20 years, more and more new construction has appeared in the area, almost all of it marketed to this new, young demographic. These developers didn’t rush here to build what the community really needed – truly affordable housing for the existing population. They were appealing in price and design to a transient market that would eventually find even here too expensive, and move on to the next new hot affordable place.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that every newcomer fit into that category. Some bought homes, joined the block associations, opened businesses and made an effort to meet the neighbors and become a part of the village. They joined families that had been on the block for generations, their well-kept homes part of a legacy of making the American Dream of home ownership a reality for black folks. In late 2021, rumors that the Eastern Star was going to sell the building to a developer galvanized this community into action. The best way to make sure the house could survive was to have it landmarked.

A city agency since 1965, when the Landmarks Law was passed, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) is charged with preserving architecturally significant, historic, and/or culturally important buildings and neighborhoods by designating them individual landmarks or larger historic districts. Once designated, those buildings cannot be arbitrarily torn down, or have their facades changed without LPC approval.

As the neighbors rallied and reached out to the community, to the city’s historic preservation community and local and city politicians, the buyer announced that he that he would be tearing the building down and building a 44-unit apartment building. He had no interest in any other use for the building and had applied for a demo permit from the Department of Buildings (DOB). The community organizers wasted no time in sending in the paperwork and preliminary research needed to ask the LPC to calendar the building for a hearing.

Meanwhile the developer began putting up fencing and having his crew gut the inside of the building. Just when it seemed hopeless, with a planned demo only weeks away, the LPC stepped in and announced that it was calendaring 441 Willoughby Avenue for a hearing. Landmark law supersedes the DOB, and the demo and other work on the building had to stop. It was like a death row last ditch appeal, with the prisoner already strapped in the chair. Those advocating for the preservation of the building were elated. The hearing would surely prove this building’s worthiness to be saved. LPC’s research staff did their own research and submitted their report at the hearing.

In the case of an individual landmark, the building must pass many different criteria for landmarking. Things that help make the case include being designed by a known and/or important architect. The building could be stylistically significant or have rare elements in its design or construction that are not found elsewhere. It needs to be in more or less original condition, the more, the better, and it helps if the building has a good backstory – who lived there, what happened there, why is it important to keep it. Also, very important to the process – is there community support for the landmarking? The Dangler mansion ticked every one of these boxes.

(Some of the homeowners and residents who organized to save the building. Photo: Anna Bradley-Smith for Brownstoner)

During the hearing, more than 75 people testified in favor of landmarking. They were neighbors, representatives from the city’s preservation organizations, and people from other neighborhoods who supported their efforts. They included local elected officials and actor Edward Norton, who was familiar with the block from his film work. Only four people testified against landmarking, two representatives of the Evening Star, who really needed to sell or face foreclosure, the developer himself and his attorney.

After the hearing, the LPC had 40 days to make their ruling. Those advocating for the building were confident that the facts and the massively positive testimony would win the day. It looked like we might have won. In the weeks that followed, the nervous developer decided to reach out to the neighborhood and plead his case. He invited them to a meeting in front of the house.

He even called many of the people who testified. I received two phone calls, one from a representative of the Evening Star, and another from the developer himself. I told both that I was firmly in favor of landmarking and there wasn’t any chance of changing my mind. The developer told me that if the building was landmarked, it was unsellable. “Nobody wants an old building,” he said. Had he never seen successfully repurposed buildings before? There were so many profitable uses for that building that didn’t involve tearing it down. When he met with the community, the developer offered them 1000 square feet of space for a community center in his new building. Really? The offer appealed to no one.

As the 40-day deadline approached, there was no word from LPC. Deadline day came, and still no ruling. The developer wasted no time. On Day 42, the backhoe and the dump trucks rolled in that morning, and before anyone knew it, the Dangler house was nothing more than a heap of brick and limestone. Neighbors and advocates watched in horror and tears as the backhoe ripped the largest tower down, the last remaining central feature of the house. It twisted sideways and collapsed. The building was gone.

(Photo: Anna Bradley-Smith for Brownstoner)

I’ve seen quite a few houses demolished, especially since I’ve moved up to Troy. I have NEVER seen a building of that size demolished so rapidly. It was obvious that the developer instructed the demo company to pull the building down as fast as possible, just in case it received another last-minute reprieve. Better to say, “Oops, so sorry,” and pay some fines for unsafe demolition than risk another stoppage. And sure enough, while the dust was still settling, a Stop Work Order arrived too late from the DOB.

The public outcry over the rapid demolition was news for days afterward. So many questions remain unanswered, the main one being, “Why didn’t the LPC make a ruling in time?” Why did they let the clock run out? Their staff spent weeks of research time, they prepared a detailed report for the hearing, with photographs and archival materials, they conducted a long public hearing, with almost a hundred people testifying and hundreds more on line listening in.

A 94-year-old woman who has lived on Willoughby Avenue for decades took an Access-A-Ride bus to LPC’s offices in Manhattan for the hearing, ready to testify, not realizing that the hearing was only virtual. LPC staffers set her up in an office with a computer so she could watch the hearing. That was how important it was. But for what? It was all a waste, a sham.

The LPC is still not answering questions. But we have many. What has the LPC become in this age of rabid over-development in almost every neighborhood in the city? They have made decisions that have contradicted their own guidelines, favoring the real estate industry over the desires and needs of neighborhoods. Of what use is landmarking if it allows a building or neighborhood to be protected only until powerful development concerns decide they want it?

The destruction of the Dangler mansion may have opened doors that needed to be opened, for it is only then that we can shine daylight on the fate of not only our historic streetscapes in New York City, but on the future of our cities and towns everywhere. This isn’t over yet.

(Thanks to Hal David via Luthor Vandross for the lyrics in the title.)

The following articles give a much clearer picture of the events leading to and during the demolition of 441 Willoughby Avenue, the Jacob Dangler mansion. They include a video of the tower coming down.

https://www.brownstoner.com/architecture/bed-stuy-dangler-441-willoughby-avenue-brooklyn-lpc-hearing-demolition/

https://www.brownstoner.com/development/jacob-dangler-mansion-brooklyn/

(Photo: Willoughby General via 6 Square Feet)

Thanks for this coverage. I'm furious too. The LPC is a total disgrace. Not only did they completely abrogate their duty, they undermined the integrity of the whole landmarking process and citizen engagement in general by wasting hundreds of people's time. Time wasted on what turned out to be an absolute sham.

As a side note, unfortunately St. Peter’s Lutheran Church was also torn down in the last couple of years.