A Quick History of the Dining Room and Its Decoration in Brooklyn and Beyond

With Thanksgiving just around the corner, we look into the room where it happens

The following story was written for Brownstoner.com and published for the first time on November 15, 2023. The images were chosen by Brownstoner editor Susan DeVries. https://www.brownstoner.com/history/dining-room-history-decor-brooklyn-nyc-thanksgiving/

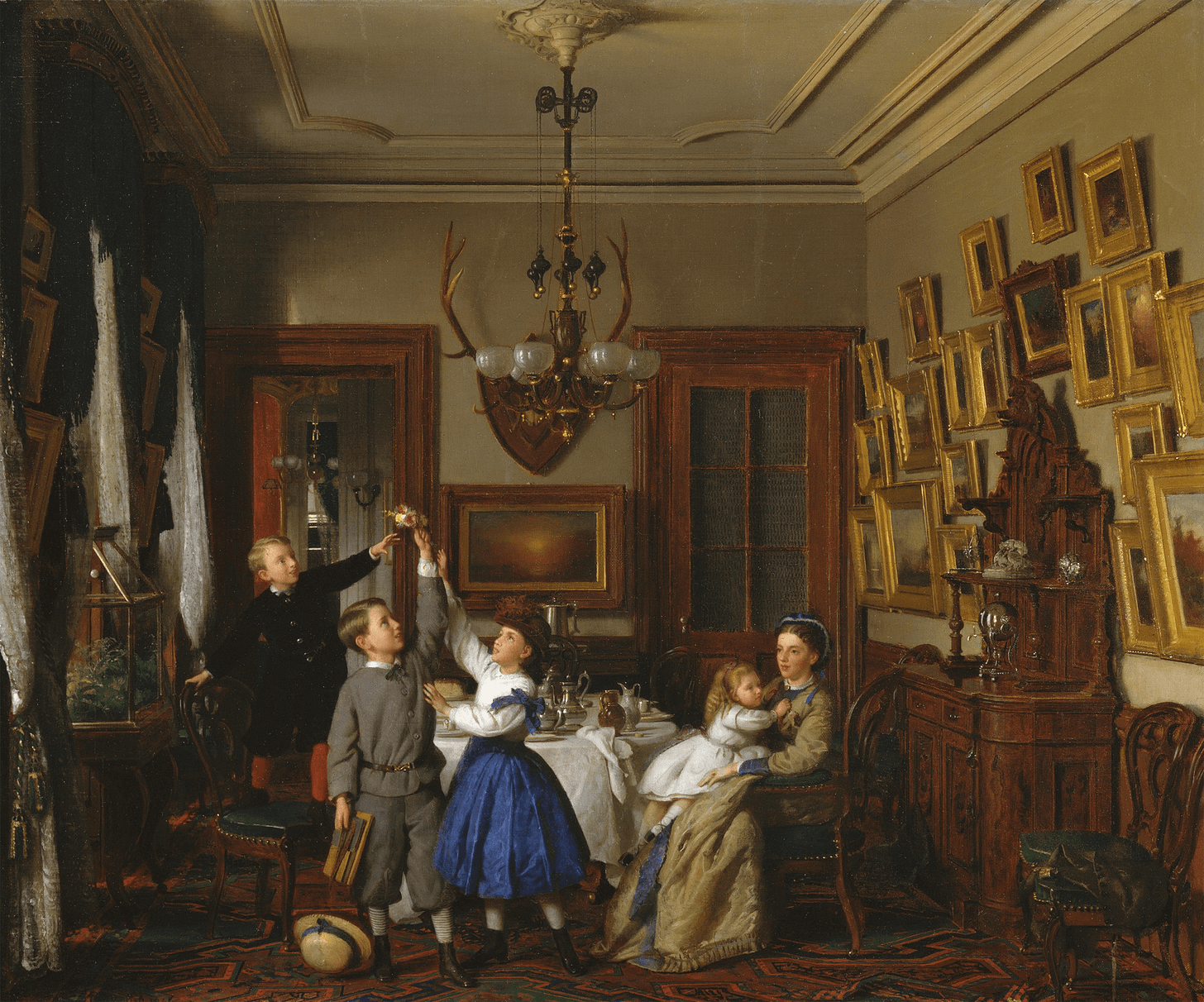

'The Contest for the Bouquet: The Family of Robert Gordon in Their New York Dining-Room' by Seymour Joseph Guy shows Frances Gordon and their children in the dining room of their Manhattan dining room in 1866. Image via Metropolitan Museum of Art

Thanksgiving was meant to be a day set aside for the giving of thanks for the harvest, the bounty of the earth, and the gifts of nature and prosperity bestowed on us throughout the year. In celebration, we gather for a feast that brings together extended family, friends, and strangers to our tables. There are only a handful of countries that celebrate a day called Thanksgiving — the U.S. and Canada chief among them — but many other countries also have traditional harvest feast days and celebrations by other names.

The now iconic Norman Rockwell image of modern Thanksgiving is multigenerational, with everyone sitting around a long table looking with awe and anticipation at a large turkey and all the fixings. Here in North America every ethnic and religious group has added their own traditions and culinary dishes to the mix.

Most of us can’t imagine our family Thanksgivings without conjuring up a vision of eating in the dining room. That space could be a dedicated room, or the corner of a larger open space, generally with a large table that can accommodate a number of people. Even if we don’t have a dedicated dining room today, the existence of one somewhere in our formative years has put it firmly in our vocabulary.

How many times in your childhood have you heard, “Get that off the dining room table, it doesn’t belong there.” The dining room was a special room. Over the centuries we’ve named most of our rooms, and although we may eat in the kitchen, in front of the TV in the living room, or while lying in bed in the bedroom (no!), there is still that one room, a special room, dedicated to sitting around the table, putting a napkin on your lap, sitting up straight and dining.

So where did this come from?

If you want to go way back in Western history, the aristocratic Greeks and Romans were among the first known to have dedicated spaces to eat. The Middle Ages gave us the Great Hall, where kings and nobility feasted in their castles and manor houses. Hollywood has had a great influence on how we visualize those rooms, some of which are historically accurate, the Red Wedding notwithstanding.

A noble family or the royals would sit at a head table, raised above the others on a dais or stage, with long trestle tables and benches below them. The rest of the diners sat according to social status, with the other nobles right below them on down to lesser people towards the back of the room. Multitudes of servants waited on them all. Most Hollywood depictions of such feasts show a rowdy atmosphere with lots of mead, people tearing meat and bread apart with bare hands, and sloppy or nonexistent manners. People ate from wooden trenchers and platters, speared food with their daggers, and forks had not been invented yet.

As time went on, the wealthy started to eat in much smaller, more private rooms, eventually creating a room just for intimate dining, albeit with more people than most of us ever dine with. But it wasn’t until the centuries of the Renaissance that the dining room evolved much closer to what we would recognize today. It was now a place of comfort where a family took its meals. The dining rooms of the 17th and 18th centuries added to the refined appearance and the importance of the room.

Here in America, the first “real” dining room is credited to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, built in 1772. He codified for future generations the style and the types of furniture that we still recognize today. Jefferson was well known for setting a fine table and entertaining guests in this room. James Hemings, Jefferson’s enslaved half-brother-in-law, was his celebrated chef. He studied in Paris for five years and introduced America to such culinary delights as pommes frites (French fries), crème brûlée, meringues and whipped cream, French vanilla ice cream, and macaroni and cheese. He also brought back to Virginia potager stove technology, the ancestor of the stoves we use today. Guests at Monticello brought Jefferson’s ideas back home with them, establishing similar dining rooms of their own.

But it is the British and American Victorians who have contributed to most to our modern dining room traditions and appearances. Of course, the wealthy could really do it up – Downton Abbey and other period British television programs feature elaborate dining rooms with massive tables that could seat 50. Those tables groaned under the weight of the multitude of sterling silver serving dishes, plates of food, candelabra, glassware, and cutlery on them. As the many courses of food were brought from the kitchen, footmen and maids served from ornate sideboards and buffets.

After dinner, the ladies would adjourn to a ladies’ parlor, while the men remained in the room, smoking cigars, drinking, and talking. The tables and other furniture were ornate and heavy, the dining room chairs comfortably designed and padded — after all, a 10-course meal in evening dress should have a little comfort.

The social habits and accoutrements of the wealthy generally made their way down the income strata to the middle classes. The middle-class family was less concerned with constantly entertaining. The focus for both upper- and middle-class life was sitting down with family. Prior to the Industrial Revolution and the growth of the middle class, families ate their most important meal at mid-day. But as cities grew, especially here in the United States, more and more people began having their largest meal in the evening. That gave the breadwinner time to commute back home so the entire family could dine together. This also led to the growing attention given to the dining room.

Factories in the United States were churning out all sorts of consumer goods for this new middle class, the people who made up the bulk of the inhabitants of Brooklyn’s row house neighborhoods. Advances in factory machinery, construction, and craftsmanship made it possible for a family to purchase more items for the home, both big and small. Style mavens emerged, writing in ladies’ magazines and newspaper articles. The “influencers” of their day informed their readers of the latest trends, the must-haves in furniture, lighting, tableware, paint colors, and wallpaper patterns.

The Astors and other wealthy families might be dining with sterling silver, hand-cut crystal, and delicate imported porcelain, but all those bespoke goods could be copied and made for the masses using lesser materials. Thus, for example, the patterns and styles of sterling silver service sets and cutlery were reproduced, often by the same silver companies, as silverplate. Upscale looks, middle-class pricing. A table in Park Slope or Bedford could look as fancy as one in Newport. Well, maybe not Newport, but close enough.

Urban townhouse design incorporated the dining room as one of the most important public rooms in a house. Throughout the 19th century, high-stooped Brooklyn row houses frequently placed the dining room at the front of the garden level, connected to the rear kitchen by a pass-through lined with cupboards. The dining room might have a fireplace, wainscoting, closet, and built-in sideboard.

By the late 1880s and into the early 20th century, many of the row houses in upscale neighborhoods had two-story extensions in the back. On the parlor level, the public level of the house where a family could receive guests and entertain, the extension was almost always reserved for a formal dining room. The kitchen was on the basement garden level below, and food was prepared and lifted to the dining room via a dumbwaiter. If the house was large enough, a small butler’s pantry used as a prep station was located next to the upper dumbwaiter door.

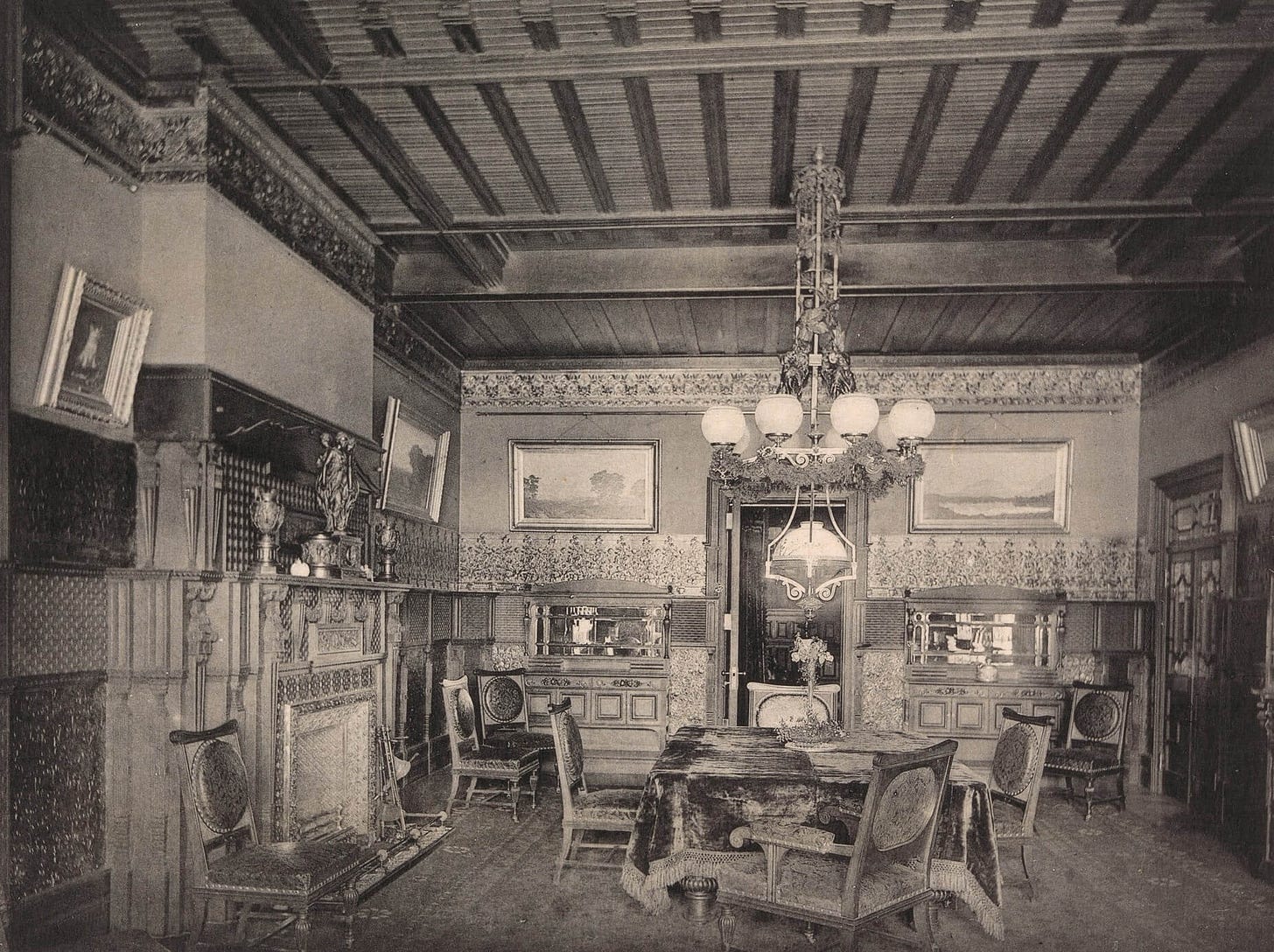

Many of these dining rooms have remained intact in our Brooklyn brownstones and are now prized by those who love the craftsmanship and beauty of a period interior. Equaling or sometimes surpassing the casework and ornament in the main parlor, the dining rooms featured tall paneling and wainscoting around the entire room, built-in sideboards and display cabinets, multiple wall sconces, an elegant center chandelier, and stained-glass windows. Many of the extensions also had large stained-glass skylights in the center of the room. The floors had fine patterned parquet borders, leaving room in the center for carpets.

In the center of the room was a large table and matching chairs. Six or eight chairs were usual, unless one had a larger family. If there were no built-in furniture pieces, a well-dressed dining room would have one or more sideboards or buffets, a China cabinet or hutch, perhaps extra chairs and a side table or two. In this new age of consumption, much attention went to the lady of the house’s public display of her fashionable dishes, silver, and crystal. Fine artwork was hung on the walls.

This assembly would last in American households for the next 100 years. The furniture styles and types of wood used changed as walnut and mahogany Victorian pieces became Stickley simplicity in oak, Colonial Revival Chippendale styles were replaced by Mid-Century Modern, which was later updated with contemporary Scandinavian styles and farmhouse chic. Today, one is able to choose from any of them and more, and still be in fashion.

As housing moved through the decades of the 20th century, builders and developers still included a dining room, whether the home was an apartment or suburban tract house. The dining room may have been reduced in size, but it was still there, just adjacent to the kitchen for easy movement of meals.

In the first two decades of the 20th century, the dining room was often located in the center of the Brooklyn row house, between the front parlor and a kitchen in a small rear extension. Sometimes known as Dutch dining rooms, these were often elaborately trimmed with paneling, embossed or tapestry-like wall coverings, plate rails, leaded-glass-fronted built-ins, and even window seats.

After World War II, the dining room became the one room in a house that didn’t get as much daily use. Suburban families became used to husbands working late and having a long commute, while children were active in more after-school programs. Many families had a sit-down Sunday dinner, but the rest of the week’s meals were becoming less structured and formal, as families hunkered down in front of the television or simply ate on the run. The dining table was used more for completing homework and as a makeshift desk than as part of a special room.

By the beginning of the 21st century, the future of the dining room looked bleak. When necessary, a dining room could become a needed bedroom, children’s playroom, or a home office. Meals were eaten in the kitchen or sitting in front of a screen. The new interior decorating mavens were touting open-plan layouts, eliminating walls to create back-to-front loft spaces. The elimination of a dedicated dining room simply meant more living space.

A dining table and chairs could be placed along a wall, near the kitchen, which also lost its walls and was now just a part of the living area, separated only by a countertop or island. The sideboard as a necessary piece of storage furniture survived as smaller multi-purpose pieces, but china display cabinets were eliminated for hidden storage units. Besides, hardly anyone picked china and silverware patterns anymore, and “Grandma’s dishes” had long been donated for resale.

But lately, many people have rediscovered the dining room, especially those who live in row houses and have the space to do so. There’s something about a traditional dining room that has resulted in many homeowners filling them with large tables and chairs, displaying dishes and other decorative objects, and maybe searching for those favorite china and silverware patterns that bring to mind memories of Thanksgivings and other family gatherings.

The family and friends gathered around the table today may look far more diverse than Norman Rockwell’s iconic illustration, but the spirit behind it is still as strong as ever – celebrating a meal with special people in a room meant for special occasions.