Attend the Tale of the Clever Barbers of First Street (And More!)

An essay celebrating Black History month and the wealth of history we are still discovering and proclaiming.

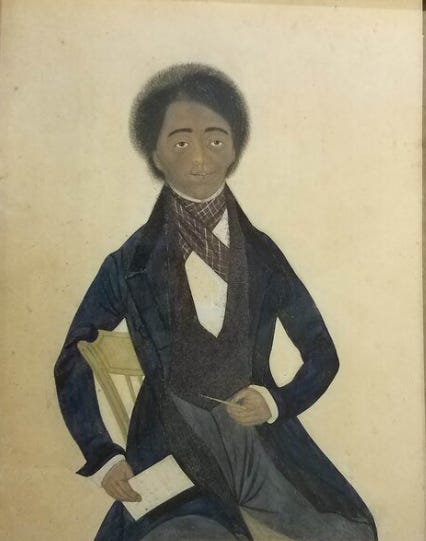

(Young Peter Baltimore, 1840. A rare portrait of an African American man from this period. In the collection of the Hart Cluett Museum, Troy, NY)

I recently presented a lecture on the great Troy civil and landscape engineer, Garnet Douglass Baltimore, who lived in the late 19th through the mid-20th century. He was the first African American to be accepted to and graduate from the prestigious Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), here in Troy. He went on to have an amazing career, a story I’ve written about before, but will revisit with a new take on the story at another time.

Long before he was accepted at RPI, Garnet and his siblings received their primary education from the William Rich School for Colored Children, also in Troy. Garnet Baltimore’s father and William Rich, the founder of the school, had a common profession that gave them financial security and prestige in the community – they were both barbers to Troy’s gentry.

The black barber played an important role in American history. Since I primarily write about history in the 19th century, I’d like to concentrate here on a couple of men that I’ve run into in various projects who all have that common thread, - they were masters of the scissors, comb and razor, and used their wealth and position to advance the cause of liberty.

Considering the tools of the trade, it’s rather amazing the power a barber wields. I’m not talking about a good or bad haircut, either. How many men have leaned back and bared their throats to a barber, fully trusting that the man holding a straight edge razor won’t be a Sweeney Todd? This was especially true during slavery, when the man holding the razor was owned by the man beneath his hand.

Throughout history, there have been the servers and the served. One of the great perks of being served is the ability to have others take care of your personal appearance, so that you don’t have to concern yourself with such details and can emerge into society in the best way possible. We’ve all grown up watching movies and television or reading books where wealthy men and women are attended by those who help them bathe, dress, get coiffed, bejeweled and otherwise primped. A good body servant was a keeper.

And so it was during the time of American slavery. By the end of the 18th century, the custom of having a trusted slave as a body servant was well established. In many cases, due to the pernicious nature of slavery, this servant was ofttimes a relative. Thomas Jefferson’s personal chef and body servant, James Hemings, who accompanied him to Paris in 1784, was his wife’s half-brother and the brother of his enslaved mistress, Sally Hemings. There are hundreds of other documented cases of these relationships.

The consensus in society at that time, whether in the North or South, was that because they were regarded as a lesser race, black people were natural servants. Men, especially, could be trained in the various aspects of being a body servant or a house servant and could perform those tasks with the grace and elegance that came to them naturally, it was thought. Their service was pleasing to behold and was superior in its servility to being served by anyone else, or any other ethnicity. Even into the mid to late-20th century, upscale restaurants and hotels employed only African American men to be waiters and bellmen. An elegant black man in livery smoothly serving a meal on a silver tray signified CLASS.

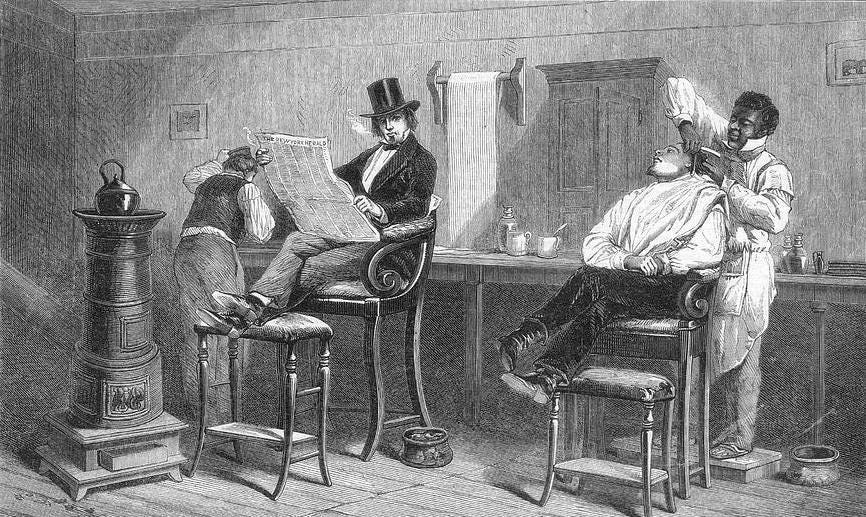

(Southern barbershop, 1840s, public domain)

Enslaved barbers were a valued commodity. They were able to turn the rather mundane task of a daily shave and occasional haircut into a luxurious pleasure. The better the barber, the more he was worth. Many barbers, especially in states like Virginia and North Carolina, would be leased out to friends and neighbors. (“I’ll have my man John visit your house and give you the best shave you’ve ever had. He’s a wonder.”) Some barbers were even allowed to set up their own shops in town. Of course, most of their money had to be handed over to their owners.

In places that either abolished slavery, or had a number of free people in it, black barbers could make a good living. They only served white patrons, as no man wanted to turn his head and see a black man getting the same luxurious treatment he was receiving. As years went by, many of these black entrepreneurs expanded their shops, offering as much luxury and as many services as possible.

One of pre-NY State emancipation’s most famous black entrepreneurs was Pierre Toussaint. He arrived in NYC in 1787 from Haiti, along with his owners, John Bérard and family. He was not a barber, but a woman’s hair dresser. While still enslaved, he became the hairdresser to New York’s wealthiest women. He made so much money that after John Bérard died, Pierre was able to amply support his widow. When she died, she freed Pierre, who named himself after the black hero of Haitian independence, Toussaint Louverture. He was successful enough to buy his sister, Rosalie, and set up shop in the city. Eventually, he married, after purchasing his own wife’s freedom.

(Pierre Toussaint, via Wikipedia)

The rest of his life was spent in doing charitable works for anyone who was in need, but especially for New York’s African American community. He sponsored orphans, mentored and sponsored apprenticeships for hundreds of young boys and orphans found out in the streets. He established a credit union, a food bank, and helped newly arriving Haitians coming to America. His most lasting achievement was being one of the financial founders of what is now the Old St. Peter’s Church, on Mulberry Street.

At his death, in 1853, at the age of 87, he was mourned by the entire city, called “one of the leading black New Yorkers of his day.” He and his wife, Juliet Noel, were buried in Old St. Peter’s cemetery, but his body was moved to lie in the crypt underneath the main altar at the new St. Peter’s Cathedral, on 5th Avenue. He is the only non-clergyman buried there, reinterred there in 1991 because of the investigations involved in his canonization as a saint by the Catholic Church. If canonized, Pierre Toussaint will become America’s first African American saint.

Many of Toussaint’s writings and letters remain, as do obituary and other articles about him that appeared in the press. Although very successful and well-liked, they reveal that at least part of that affection was from the hairdresser being the kind of black man his patrons and admirers found to be admirable. The New York Post (yes, it’s been around that long) wrote glowingly in his obituary that he could have been the model for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s title character in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Toussaint, and many others knew that assuming this deferential posture was the difference between starving and success. He was willing to go that route. It was pragmatic and allowed him to achieve success, and to help his family, his people, and others in need. His family and friends knew he didn’t believe himself to be inferior, although from letters to friends he was often despondent from having to live in such a manner. He certainly could qualify for sainthood.

By the mid-1800s, before the Civil War, Black barbers in cities like NY, Troy and Philadelphia made their livings by offering more than just a room with a chair to their white patrons. They offered luxury and spa-like accommodations. For once, they had a rare advantage over new immigrants coming into cities offering their own tonsorial services. They had been there longer, and thus had the better locations. They were often occupying prime real estate, close to businesses and banking, where they knew their clientele would be.

“The Veranda,” Peter Baltimore’s shop, on left, next to the Troy Atheneum. Neither still stand. Photo: Hart Cluett Museum, Troy.)

In Troy, Garnet Baltimore’s father Peter Baltimore had a well-established and well-known shop on First Street in downtown Troy. First Street was “Banker’s Row,” with many of the growing city’s banks, brokers and insurance companies. His clients would come in and enjoy a world made for them, with fine woodwork, gas lighting and furnishings, comfortable barber’s chairs and waiting room seating. They would be offered a glass of good whiskey, and could choose a smoke from a humidor with the finest Cuban cigars. If they wanted, a manicure was available, and a gentlemen’s jacket or coat could be freshened while he waited. Baltimore’s shop was called “The Veranda.”

There, behind his leather barber’s chair would be Peter Baltimore himself, a master of the close shave and the stylish haircut. A man would sit, have his face swathed with a hot damp towel, softly scented in a popular men’s fragrance. And while these powerful men were pampered, they talked.

Often the talk was about local finance or society, sometimes it was about local and national politics, or philosophy. Horse racing or athletics or local gossip were up for discussion, it didn’t matter, Peter Baltimore listened well, and could chat on those and any other subject. He was well-read, a great conversationalist, an excellent listener, and was accounted as a witty and funny man. His customers enjoyed going there.

Testing the room and knowing his customers, it is likely that Baltimore talked about the biggest topic of its day – slavery in the Southern States, and the possibility of war. His father had been enslaved, and after freeing himself by heading north, had married and raised his family in Troy. He was a respected restauranteur. Baltimore and his family were living proof that black people were hard-working and deserving of freedom. Slavery was probably a big topic, especially after 1850, when the Fugitive Slave Law allowed Southern slave owners or their slave catchers to reclaim their property.

What many of his well-heeled patrons may not have known is that their beloved Veranda was also a station on the Underground Railroad. Peter Baltimore was one of the leaders in Troy’s anti-slavery movement and used his shop as a way station to freedom.

William Rich was also a prominent black Trojan and a successful barber. He was born in 1800 and was older than Peter Baltimore, who was born in 1829. He came to Troy from Worcester, Massachusetts, where he had been part of the household staff of Governor Levi Lincoln. He opened his first barbershop in Troy on River and Ferry Street in 1824, and then relocated his shop to the River House Hotel, where he operated for 46 years, before moving for the last time to Troy’s Post Office building. Rich would have already been at Trojan House when Baltimore opened his emporium right next door.

(Troy House hotel. Photo: Hart Cluett Museum, Troy)

The two men may have been friendly rivals in business, but there was plenty of work for all. They were also firm allies in the cause of abolition. William Rich was quite publicly one of the heads of Troy’s Vigilance Committee, which advocated for the end of slavery, and was also a part of the very active Underground Railroad in Troy. Between the two of them, they were able to use Troy House as place of employment for escapees who wanted to stay in Troy, whether temporarily or permanently. Many were hired as busboys, janitors and waiters. They could also be hidden nearby, perhaps in the basements, if necessary.

Rich was credited with feeding and caring for hundreds of fugitives, some accounts saying he would get groups of more than 20 people at a time. Troy was not a city that supported slavery or the Fugitive Slave Act, as was shown in the dramatic rescue in 1860 of captured fugitive Charles Nalle, only half a block away from both men’s shops. They were most likely aided, if only financially, by some of their wealthy and well-connected white patrons.

After the war, William Rich helped found the city’s only Colored School, which was named after him. He was also one of the founders and trustees of the Liberty Street Colored Presbyterian Church. He was a pillar of the black community in Troy, and when he died in 1880, was lauded in The Troy Daily Times as “the most prominent colored man in the annals of Troy.” He prospered in business and was able to use some of his fortune to “promote the welfare of his race.”

That would not have been possible, had he not been in a service industry. Peter Baltimore and Pierre Toussaint, the same. They were able to use their skills to make a better living for themselves and their families and were able to use their positions as established reputable and popular businesses as fronts for the greatest civic disobedience of the 19th century – the cause of abolition and the active aid to escapees from that hated institution.

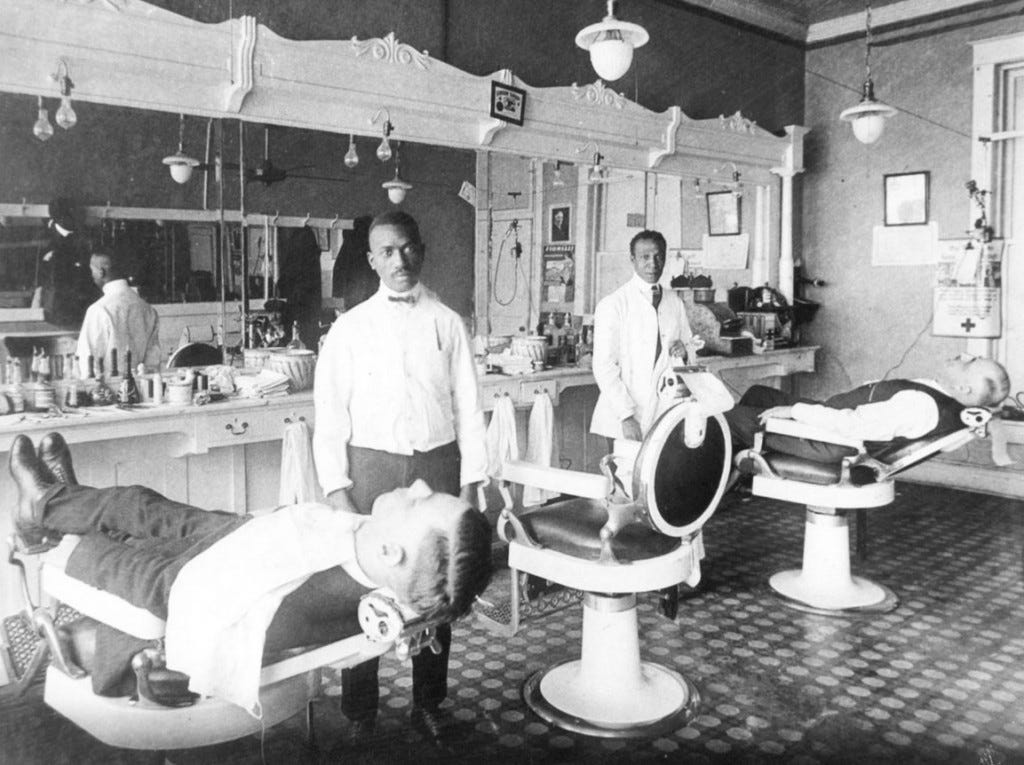

There has been quite a bit of research and writing done in the past few years highlighting the importance of barbers and barbershops in black America. They went from catering only to wealthy white men to being successful businesses in the growing black communities throughout the country. Black barbers joined undertakers, ministers, teachers, pharmacists, doctors and lawyers as the upper middle-class members of black society, especially in racially segregated America. Their place in American history has only begun to be explored.

For more on the topic of black barbers and their importance to American life, please check Cutting Along the Color Line, by Quincy T. Mills, professor of history at Vassar College. His book and interviews were valuable resources for this essay.)

(Photo: Library of Congress)

A wonderful article, Suzanne

https://www.iloveny.com/listing/new-york-state-civilian-conservation-corps-museum/2896/

CCC Camps is in Laurens, near Gilbertsville.

Another great article,

Matt