Bannerman Island and the Improbable Ruined Castle On the Hudson

I'm always fascinated by ruins and a good story. We've got both, in the Hudson Valley

For those who deal in arms, war is a business, a very lucrative one, at that. Historians look to the sale of arms to the Indigenous people of the Americas by Dutch traders in the 1600s as the start of the arms business in America. Before the American Revolution, the colonies didn’t have widespread arms or gunpowder manufacturing capabilities, and the British were pretty successful at keeping it that way. The Colonial Militia had to retreat from the Battle of Bunker Hill because they ran out of ammunition. It wasn’t until the Continental Army began getting guns and ammo from the French that the tide of battle began to turn.

After the war, the new American government, without partisanship, concluded that if the United States was going to remain independent and grow with the great nations of the world, it was going to have to be self-sufficient in the manufacture and stockpiling of all kinds of arms and ammunition. The government set up state-run arsenals, and private companies began manufacturing firearms and ammunition to fill them. By the time the War of 1812 erupted, the United States was not only self-sufficient in arms, American arms companies were already exporting arms to South America and the Caribbean, changing European colonial history in the Americas.

By the time the Civil War erupted in 1860, there were arms dealers and arsenals on both sides. The most famous one was the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, which was established back in George Washington’s time. After the war, there were tons of surplus materials and weapons all over the United States. A new kind of wholesaler emerged, one who dealt in the purchase and sale of used war materials.

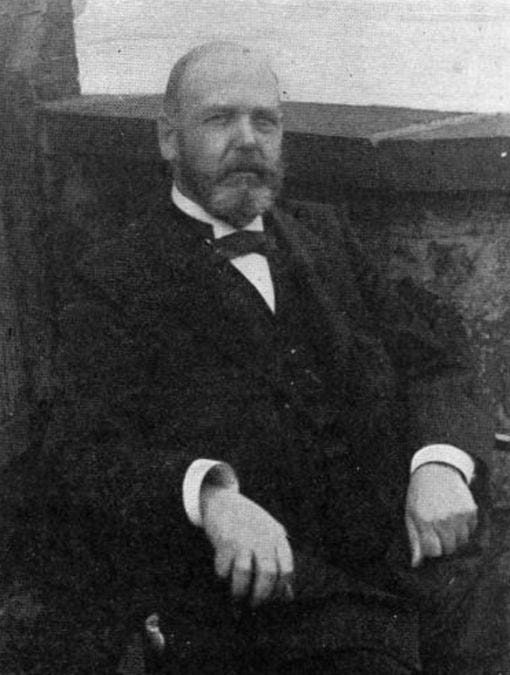

Francis Bannerman was born in Dundee, Scotland. He came to the United States in 1854 with his parents at the age of three. He was a descendant of a Scotsman of the McDonald clan who, during the battle of Bannockburn in 1314, captured an enemy Campbell flag and escaped into the hills with it. King Robert the Bruce was so impressed he bestowed upon him the title of “banner man,” which eventually became the family name. With that sort of heritage, it’s no wonder that the family was especially industrious in making their mark in America.

Francis’s father established a business selling and buying Navy surplus and scrap. The family lived only blocks from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and young Francis spent his afternoons and weekends collecting scrap from the busy harbor. His father enlisted in the Union Navy, but not before teaching the adolescent Francis everything he knew about the Navy surplus and auctions. The boy became the family breadwinner. He quit school and spent his days dredging Wallabout Bay with a rope and grappling hook, selling the scrap metal and finding objects that he could sell. He was so successful that when his father returned, the Bannerman business was up and running, with 15-year-old Francis in charge

The end of the Civil War was a dream come true for surplus dealers. Because of young Bannerman’s business acumen, he and his family started one of the first military surplus stores. The United States government had tons upon tons of military surplus and began selling it off as scrap. Francis’ business purchased every cannonball, sword, gun and bullet that he could. Most scrappers were buying for the metal itself, but Frank figured out that more profit could be had if the weaponry could be resold. By the age of 20, Bannerman was a successful second-hand arms dealer.

The first Bannerman’s headquarters and stores were in Brooklyn near the Navy Yard. He later moved to an old rope factory on Atlantic Avenue, but that was soon too small, as well. They moved several times as the amount of stock increased, and finally ended up at 501 Broadway, Manhattan, in SoHo near Spring Street. During this time, he did a brisk business in surplus cannons. A great many of the cannons today found in war memorials, battlefields and parks across the country came from Bannerman’s.

In 1898, the United States and Spain went to war. It lasted three months and was fought primarily in Cuba and the Philippines. The war resulted in the largest supply of miliary surplus since the end of the Civil War. Bannerman sailed to Cuba and was on hand to purchase nearly every piece of military goods surrendered by the Spanish, which included thousands of Spanish rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition.

He didn’t have just guns and ammo, Bannerman also bought and sold everything a modern army of its day might need – uniforms, saddles, knapsacks, holsters, meal kits, etc. He was able to supply the Japanese army with armaments and more during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904. He even sold old uniforms as costumes for Buffalo Bill and supplied military uniforms for other theatrical productions.

Bannerman’s warehouses in Manhattan were bursting at the seams. New York City had strict laws about live ammunition in the city, and he had over 30 million rounds of live ammo on hand. By this time, both of his sons were working for him, Francis VII and David. A new solution was needed. The perfect location for all his arms and ammo would be his own little island outside of the city limits. Francis Bannerman knew exactly where such an ideal place was located.

It was called Pollepel Island, and was only about 50 miles from NYC, on the Hudson River. Better yet, it was only about five and a half miles upriver from West Point and easily accessible to the shore by boat. His son David discovered the almost-seven-acre island on a canoeing trip. Bannerman bought it from the Taft family in 1900.

Pollepel Island had never been inhabited. Local indigenous legends told of the island being visited by the Storm King and his goblins, the spirit of the impressive rocky mountain across the river from the island. The name Pollepel in Dutch translates as “potladle.” Drunken Dutch sailors were also called pollepels and were left on the island to sober up and be picked up on a boat’s return. The more fanciful legend told of a girl named Polly Pell and two companions who fell through the ice one winter and were saved by making it to the island. Bannerman loved all this information, it added to the mystique, and set about the business of building a place to store his wares.

Bannerman designed a castle, based on the architecture of Scottish castles, with the elements of other styles he liked tossed in as well. It was designed to be an arsenal and warehouse. Construction began in 1901. He also built a separate mini-castle, a summer home for the family, behind the main building. He and his wife spent the next 18 years adding to the castle and grounds. Helen Bannerman, born in Ireland, laid out gardens, establishing pathways and terraces with shrubs and plants and helped her husband design the perfect summer home. Their small castle had a picture window that faced the Hudson River and West Point.

Bannerman built a breakwater and harbor around much of the island using thousands of Springfield rifles as rebar. He positioned two small turrets as guardians into his harbor, with arched turrets on the southern side. He also designed a working drawbridge. He hired local tradesmen to build the complex but never hired an architect or engineer to supervise construction. He left his contractors to figure things out for themselves. When the main building was completed, the name Bannerman’s Island Arsenal was prominently positioned so that it could be seen for miles and was an impressive advertisement.

A large percentage of the Bannerman business was carried out via catalog. The Bannerman’s catalog was published from 1880 up until the 1960s. In it one could find just about anything related to the art of war. They sold crossbows, Civil War arms, and weapons from the Philippines – native bolos and tribal wall shields. If you wanted a suit of armor for your own castle, Bannerman had those too. They sold authentic collector’s items, especially firearms and swords, from every era, some belonging to famous or infamous figures. He also wasn’t above a little “factual exaggeration” with some of those items. Regardless, the Bannerman catalogs today are seen as the best reference ever written on weapons of war.

The Bannerman family summered on the island for years. It must have been like vacationing on the side of an active volcano because the tons of ammunition stuffed throughout the rooms of the castle and in the later adjoining warehouses could explode without warning. Summer sun, rooms full of gunpowder and shells, perhaps a ray of sunlight focused on something flammable – you never know. Boom.

Francis didn’t just want his island to be a warehouse, he wanted it to be a museum, showing hundreds of years of weapons and accoutrements of war around the world. For all his participation as a major arms dealer, Bannerman saw himself as a man of peace, and wanted his museum to show what he hoped to be ‘The Museum of the Lost Arts” those arts being war. He was a devoted churchgoer and contributed blankets and uniforms to the US Government during World War I. He also gave them cannons.

He was active in a local boy’s club and often invited them to the island during the summer. His museum was never truly realized, partially because the US and other nations continued to wage war and needed his goods. As the technology of war advanced, more and more goods became outdated and surplus, and that meant more merchandise for the Bannerman’s to buy and sell.

The United States didn’t enter World War I until it was almost over. But that didn’t mean that the country wasn’t already in the grip of spy hysteria. Enemies could be anywhere. In April 1918, a US Navy submarine chaser landed 19 men on the island and rapidly took control of it. One of the Bannerman employees was an Austrian immigrant who was arrested on charges of spying. They put Bannerman under house arrest in his home castle and searched the entire island for evidence of German espionage.

Bannerman was furious. He and his attorney got the house arrest dropped as he sent an angry letter to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt demanding the sailors leave his island, as he and his family had a firm reputation as American patriots. He was eventually issued a formal apology and the occupation was discontinued.

All that excitement didn’t help his health any. Francis was also involved in a large relief operation in Belgium and that project and the incursion and house arrest took a toll. Francis Bannerman died in 1918, of overwork, his NY Times obituary read. He was only 68. His sons inherited the business and the island, but they were not as invested in the family castle in the Hudson. They concentrated on their catalog and their business operations, in Manhattan and Long Island, and the castle was neglected.

In the summer of 1920, the inevitable happened. The heat or a lightning strike caused one of the munitions rooms to blow up. 200 pounds of gunpowder and shells blew the side of that part of the building out, with debris landing in the river and on the railroad tracks on shore. Helen Bannerman was on the island and was slightly hurt. The arms business really went downhill for the Bannerman brothers after that. Most of their commerce now was selling to collectors and the Great Depression further crushed even that.

In 1950, the ferryboat Pollepel, which docked on the island sank in a sudden storm. That year the state and federal governments also passed laws banning the sale of military weapons to civilians. The Bannerman sons died in 1945 and 1957. No members of the family were interested in continuing the business and the warehouses in NYC were sold. In 1958, the explosive contents of the storerooms on the island were removed and some of the contents were donated to the Smithsonian. That same year, Charles Bannerman, Frank’s grandson, sold the island to New York State.

The Parks Department searched the buildings to make sure no ordinance was left and opened the island to tour groups in 1968. But in 1969, a huge fire engulfed the arsenal, destroying the floors and ceilings, leaving only the shell of the main building standing. Arson was suspected, but nothing could be proved. The island was declared off-limits to everyone. The buildings continued to further deteriorate and despite the ban, vandals and trespassers further compromised the buildings.

As the castle continued to fall apart, a curious discovery was made. Never one to waste anything, Bannerman had instructed his contractors to use recycled bed frames, bayonets, old mattresses and other military salvage to bulk up the cement-covered brick construction. All were found in the crumbling walls. It was a wonder as much of the building was still as intact as it was.

That didn’t last long. The winter of 2009-10 was a harsh one. In December, fierce storms rode the tides up the Hudson, and the wind blasted down from Storm King Mountain. The already weakened building couldn’t take it. Witnesses saw the southeast side of the building collapse taking with it half of the front wall and a third of the eastern wall and staircase. The wall with the Bannerman name was gone.

Beacon, NY resident Neil Caplan founded the Bannerman Castle Trust to raise money to save what was left of the site. Over a million dollars has been donated, which has been used to stablilize and shore up the remaining castle walls. Much more is needed. The summer cottage, which can barely be seen from the eastern side of the river, or from the Amtrak tracks, is much more intact, as are other small parts of what was a very large complex. Work still is ongoing to save as much as possible.

Today, tours operated by the Trust are as popular as ever. Boats leave both Newburgh and Beacon and dock on the side of the island, allowing people to visit safe portions of the castle. Kayak tours are also available. The Trust also hosts special events there, in the shadow of the walls. Francis Bannerman wanted his castle to be a museum for peace. He would have been surprised that the ruins of his dream oddly have been realized.

Spotting Bannerman Castle is always a highlight for me when travelling on Amtrak to and from New York City and Albany. I’ve even managed to get a few photographs as the train passes. Whenever I hear fellow passengers ask what it is, I tell them the story.

For information on visiting the island see the Bannerman Castle Trust’s website: https://bannermancastle.org/

Very interesting stuff, thank you! Little number transposition - the battle of Bannockburn was in 1314, not 1614.

Just had a look at Google earth, it seems much worse than the "Present day aerial view. Via Militaria" unfortunately.

I took a tour of the island in 2009 when the main castle was but four walls. The residence on the hill had been completely vandalized, but the tour guides gave us a great look at the fascinating history.

They said the interior of the warehouse was built from timber taken from ships, tarred and soaked in creosote, which fed the conflagration. In spite of best efforts, the walls keep falling and there's not much left. Here's an album of my photos from that trip: https://www.flickr.com/photos/widdgget/albums/72157633744308787/