Brooklyn's Glass House Disaster

A version of this story originally posted on brownstoner.com in 2010

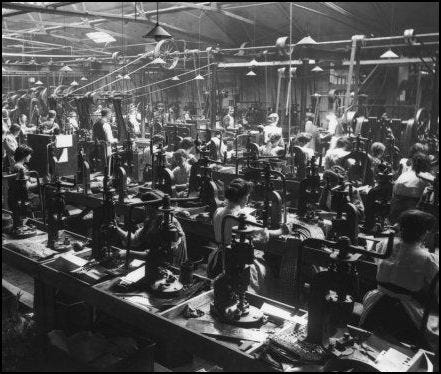

(Brassworks factory, 1900. Photo: Museum of the City of NY)

The block bordered by Atlantic Avenue, Hicks, State and Columbia streets in Brooklyn Heights has long been a mixture of industrial and residential buildings and has had quite a colorful past. Today, Atlantic Avenue houses the iconic bar Montero’s, with tenement storefronts lining the street, and along Hicks. Behind it, on State, new construction apartments and garages line the street, ending in the cut off for the Brooklyn Queens Expressway. Before the expressway ramp was built, the street extended almost to the harbor.

Back in 1885, the block was part of Brooklyn’s industrial fabric, as well as home to the workers who toiled in its factories. Behind the then wood-framed tenements of Atlantic Avenue, a group of connected factories, centered on the site of a glass factory that had burned out years before, took up most of the lots on State Street. The central building was still called the “glass house,” although it had not been one for quite a while.

To enter this compound, one would pass through a two-story wood-frame gateway building with an entrance on Atlantic Avenue. The agent for the building, George L. Abbot, had an office here, where he managed all the factory properties in the complex. For such a relatively small industrial hub, there were many businesses in operation there, around eighteen businesses in all, employing somewhere around 500 people. That did not include those who lived in the tenements whose back walls butted up against some of the factory buildings. If you think this sounds like the lead-in for a disaster, you are correct. At 9:20 a.m. on May 5, 1885, that disaster happened.

Today, most of these companies would never be allowed to be in such proximity to each other, but in 1885, this was commonplace, as was the child labor in these factories. The main building, the old glass house, was a five-story building. The top floor housed the Henry L. Judd Company, a window roller shade company. They also occupied space in one of the other buildings and employed about 300 people.

Below them on the fourth floor was C.W. Butler & Co., tin dealers, who shared the floor with budding paint manufacturer, Benjamin Moore. His company manufactured Calsome Finish, one of the company’s earliest paints, on this floor and part of the floor beneath it. A manufacturer of oleo margarine had also rented space on the third floor but had recently moved out.

On the second floor was William Durst, a brass works foundry, and on the ground floor were the separate shops of two machinists, George Young and William Daniels. The other businesses in the surrounding factory wings held manufacturing or workshop space for a button company, a scouring soap manufacturer, two watch case makers, a rubber works, a pencil case maker, a gold refining company, another metal shop, another machinist, and a rod trimmings shop, among others.

The old glass house building was, well… old. It had survived two fires that had practically gutted it and was supported by the other buildings around it. Workmen and tenants would later testify that the walls were weak, and the cellar was a swamp, with large amounts of standing water. Waste pipes from the now-departed oleo margarine company, as well as the industrial soap manufacturer in the complex, had backed up, dumping so much water in the cellar that boards had to be placed on the floor so people could walk there. The wooden posts holding the building up stood in chemically laced water that had accumulated for years.

The support beams on the western side of the building were sagging to the point that the machinists could not get their machinery plumb. George Abbott, the agent for the complex, had received years of complaints, which had finally reached the state where he was pressured to actually address the problem. He hired a house mover by the name of John McDermott, a mason named Frank Miller, and a carpenter named Peter Watson to head workers who would replace the posts and beams in the basement and jack up the floors. Abbott did not tell the tenants that this work was being done during workdays, while the buildings were in full occupancy and operation.

The workmen went below into the cellar and began to replace the beams, sistering new wooden beams aside the old ones. They needed to drain the floor and pour concrete foundations for the new posts, which would be capped by bluestone. These would secure the floors, while also jacking them up, raising them back to plumb. After the cement was set and cured, and the new beams secured to the building, the old, rotted beams and posts were to be removed, and everything would, in theory, be fine. The work proceeded, even though no permits were sought or obtained, no engineers were consulted, and none of the men involved had ever done this sort of job before.

On the morning of May 5, 1885, the factories were all in full production. The soap manufacturer had recently received a delivery of over a ton of silicate for production, adding to stock already there. The heavy machinery used by the ground floor machinists was humming and vibrating with use, clanging out their parts and pieces. Above, and in the other wings, production at Benjamin Moore’s paint factory was in swing, the gold refiner was melting down old jewelry, the watchmakers were casting silver, the brass works were spinning out hardware, and the young girls in the button factory were busy at their cast iron presses, making covered buttons. On the top floor, workers; mostly teenaged boys and girls, were busy sewing and assembling roller window shades.

Down in the basement of the glass house building, the new beams had been installed for a couple of weeks, but because the floors were still so wet, the cement could not set or cure properly, so the posts were not truly secured or stable. Impatient to get the job done, George Abbott had McDermott, Miller, Watson, and their men remove the pins from the old beams, knock them down, and allowed the building to be supported solely on the new beams, resting on the new posts. That job done, the men made their way outside.

Suddenly the glass house building started to shake. Workers inside would later testify that the walls abutting the tenement buildings started to collapse. William Durst, owner of the brass factory on the second floor, testified that a funnel shaped hole opened in the floor, and everything started to collapse inward and down. Heavy machinery fell through the floors. Businesses with open fires saw those fires spill out into the rooms, and chemicals and flammable materials instantly ignited. The collapsing walls took down other walls, and fire and destruction spread throughout the entire factory complex, and to the adjoining tenements.

To those workers and tenants in the block of Atlantic, State, Hicks and Columbia, it was as if the end of the world had come.

Henry Durst, William’s uncle, disappeared into the hole along with tons of equipment, much of it super-heated and already on fire, along with four other employees, including a 15 year old boy. William and several co-workers were able to jump down to the floor below, and escape through the windows before the rest of the building fell. One of the workers in one of the ground floor machinist shops said that they saw bricks start to fall from the ceiling, and then saw the walls spreading, and the floor opening, and they were able to run out of the front entrance to safety before the entire building collapsed. Far too many were not as lucky.

In the button factory on the top floor of one of the adjoining buildings, the teenaged, mostly female employees were shocked from their work by the sound of the glass house collapsing, followed by part of the floor in their own building collapsing. Most of them and their employer were able to climb a ladder to the roof and escape to an unaffected building, and down a fire escape. Fire and smoke soon began to pour from one of the adjoining tenements, and then their factory windows. At least 5 girls and one male supervisor did not make it out.

As building after building began catching fire, the collapsing walls crashed into the backs of the wooden tenements, pulling the backs down, and sending bricks and debris into the apartments. Fortunately, people were able to escape to the street from the front of the buildings, but people risked life and limb to rescue family members and pets. The fires were caused by broken gas lines and the businesses that used open flame, including the gold and silver workshops, the brass foundry and other metalworkers. The fires mixed with open chemicals from some of the other businesses, as well as tons of flammable materials like fabric, window shades and paint.

The soap manufacturer, which made “Pride of the Kitchen Soap”, had just received a ton of silica, used in the making of their products. Employees often joked that they risked their lives every time a delivery came in, which filled their space from floor to ceiling, and made the floorboards of the old factory creak. When the building collapsed, the silica mixed with water from burst pipes, and heated by the fire, oozed down the factory walls into the basement, where it spread, a gelatinous and deadly mess.

Paint maker Benjamin Moore was initially thought to have been missing, but turned up later. He had been in another part of the building complex when the glass house came down and was able to get the nine girls in that part of the plant out safely through one of the State Street exits. Charles Schwetter, who manufactured gold watch cases on the third floor of one of the extensions, got himself and all of his employees out in time. He left behind significant amounts of gold which melted in the heat of the fire and fell to the basement below.

The fire department was at the scene within fifteen minutes after the alarm was sounded. Almost to the hour, at 10 am, the walls of the factory building facing State Street collapsed, exposing the rest of the complex to the street, making it much easier for firemen to pump water onto the blazes.

The first thing the police did was take mason Frank Miller into custody, the common thought being that there was no way he could have escaped if the collapse had truly been an accident due to some other factor other than the beams. But it soon became quite clear that finding and identifying the dead was going to be much more difficult than finding someone to blame.

As the fires were brought under control, a growing list of the missing and presumed dead began to grow. Among the first bodies found was that of the janitor of the complex, Daniel Loughery. He lived with his wife and daughter in the Atlantic Avenue tenements and had rushed to help rescue people. His wife and child were not at home, fortunately for them, as the flaming debris had torn out the backs of his row of houses. His body was found under the debris of the glass house, the extent of his injuries so severe, he must have been killed instantly.

In the days that followed, more and more bodies turned up, to add to the seven found on the first day. Many were so badly burned that it was impossible to guess gender or identity. Most gruesomely, in some cases only burned body parts, not even whole corpses were found. Some were identified by personal possessions, or their place in the wreckage. One man was identified by a false tooth.

Recovery work was slow and made difficult by the nature of the industries and the basement collapse. Many of the dead came from Durst’s brass foundry on the second floor. None of them had a chance. It took time for the workers to extricate the body of Henry Durst, as he was found in the bottom of the basement, but his body was completely encased in the gelatinous mass of soap and silicate, which had poured down from the soap factory and congealed in the water-soaked basement.

While most of the rescue workers were working to clear out the site, many had heard of the thousands of dollars in gold and silver that had melted in the fire, and searches for melted treasure were combined with searches for bodies, slowing down the recovery. Tons of silica made the entire site a recovery nightmare, as bones and more and more parts of the dead were unearthed in the muck.

There was good news as well, as some feared dead turned up in hospitals, or safe. There were many heroes that day, bosses and supervisors who made sure all their workers got out, brave co-workers who shepherded many of the very young, female factory workers to safety. At least four firefighters were hospitalized for injuries sustained in rescues, including the rescue of an elderly lady named Mrs. Haas, who lived in the tenements, and had a wall fall on her. She would make a full recovery.

When the police and investigators first arrived at the scene, building manager George Abbott would not even tell them the name of the owner, apparently hoping to keep the whole incident out of the press. He had to be threatened before notifying his employer, who lived in Boston. The police initially just arrested Frank Miller, one of the three contractors who did the repairs to the support beams. They did not arrest Abbott.

As the days went by, and funerals were held, and witnesses interviewed, a coroner’s inquest was held on May 15, 1885. The jury would listen to testimony for over ten days. During the questioning, the following was made clear:

1. George Abbott, the building manager, had let the conditions of the glass house factory deteriorate over the years, and was deaf to the complaints of tenants.

2. He never replaced the fire escapes in the glass house building after the last fire, several years before. The other buildings did have fire escapes.

3. He hired the three contractors to replace the rotted beams and posts, knowing that they had never done this kind of job before.

4. The contractors did not get a permit from the Buildings Department, nor did Abbott insist that they do so. One of the contractors, house mover John McDermott, testified that he didn’t apply for a permit because he didn’t think it was his place to do so. Abbott testified that he thought the contractors would be responsible for their own permits. He never checked to see if they had them.

5. Abbott also testified that he told the workmen to take the jacks and old beams out, so the building was resting on the new beams, even though the load bearing posts were not truly secured. He then testified that he really didn’t know much about building construction.

6. When asked about his not notifying the tenants that this work would be going on during the workday, Abbott said that he had told Mr. Durst on the second floor. Durst would lose the most workers in the collapse, including his uncle. He said he informed no one else.

7. When asked by Coroner Menninger about why the building collapsed, Abbott said it was because of the beams. When asked whose fault that was, Abbott replied, “I shouldn’t like to say.”

After days of testimony and evidence, including a trip to the ruined factory block, the jury of thirteen men in the Coroner’s inquest deliberated. All of them agreed that George Abbott was culpably and criminally negligent, in causing repairs to be done while the factories were occupied and in operation. He also was negligent in supervising work that he did not have the expertise to supervise. They all agreed that more building inspectors were needed, and that the Dept. of Buildings needed to change the way it inspected factories and needed to keep better records of inspections and findings.

Eight of the jurors also found the three contractors, Miller, McDermott and Watson to be guilty of contributory negligence, and two building inspectors guilty of careless and superficial inspection of the building in previous visits. Three other jurors agreed with the above but exonerated the three contractors. Another juror agreed with the majority, but exonerated the inspectors, while one other juror placed all the blame on Abbott, with a scolding to the inspectors. The Coroner took his findings to the District Attorney, who arrested George Abbott, Miller, McDermott and Watson, and held them for trial. If found guilty, they could be sentenced to 15 years in prison.

The charges were dropped against Watson, McDermott and Miller, by the summer. George Abbott made bail in August. Public opinion was not on his side, as the Brooklyn Eagle wrote several editorials about the fire, the loss of seventeen lives, and the guilt of the man who had so cavalierly ordered major structural work in a building full of people, without their knowledge or consent. In October of 1885, Abbott was again in court, and then……the case simply disappeared.

Three years later, in 1888, the Eagle wrote another editorial slamming the judicial system that had allowed this high-profile case to simple slide off the table like greasy paper. They were complaining that this was not the only case that had mysteriously disappeared. Regarding the horrific fire, the Eagle wrote: “The Eagle will recall the facts in the awful State Street fire, by which seventeen lives were lost on Tuesday, May 5, 1885. The ruins of that conflagration still rear aloft their blackened chimneys and ragged walls, and the memory of the catastrophe, except in the District Attorney’s office, is fresh as it was three years ago. In the District Attorney’s office, the event seems to have been forgotten altogether…”

“The State Street fire, was with the exception of the Brooklyn Theater fire, perhaps as shocking as any in the history of the city… (Followed by a description of the fire and casualties and the cause) A true bill of manslaughter in the second degree was found against him [George Abbott] by the Grand Jury on July 31, 1885…On October 9th; Abbott was arraigned in court and pleaded not guilty. That was the last step ever taken on the case. It never came to trial, and the record in the office of the clerk of the Court of Sessions shows that it now stands as it did three years ago, while Abbott, who was judged to be criminally responsible by the representative businessmen of the city, has enjoyed continuous and unrestricted liberty. Abbott had some sort of pull.”

And so ended the investigation of one of the worst industrial disasters in Brooklyn’s history, an event that today, no one knows about at all. Next time you are in Montero’s, raise a glass to the 17 people who died horribly and tragically that day in 1885. Most tragically, they never got justice, and no one ever paid for the mistakes made that day.

(Covered button factory, public domain, and layout of the buildings in the glass house compound. Latter via the Brooklyn Eagle.)

Fascinating...conjures up the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, another disaster where the culpable owners got away with murder--although public outrage did eventually lead to changes in laws and support for unions. Thanks for writing this.