Cast In Iron, Made for the Ages, Unlike Us

Soho has great architecture. Before it became a tourist mall, Broadway and the side streets were great places to roam and gawk. I started working there in the early 1980s. It was different then.

Like many people in Greater New York City, most of the jobs I had while I lived in the city were in Manhattan. My stint at Saks Fifth Avenue, on 50th and Fifth Avenue was the only job I had that was located above 34th Street. The remainder of my Manhattan jobs were in the area around W. 23rd Street and Madison Park, or below 14th Street, in NoHo or SoHo, between Greenwich Village and Tribeca.

Houston Street (How-stun, for you non-NYers) is the dividing line between SoHo – South of Houston, and NoHo – North of Houston. The SoHo neighborhood runs from the north side of Canal Street to Houston, and NoHo extends north of Houston to Astor Place. Both neighborhoods have a great deal of similarities in terms of general history and architecture, but for this story, my attention will be focused on SoHo.

Soho, (so much easier to type, and both versions are used) is described by Google Maps thusly: “Designer boutiques, fancy chain stores and high-end art galleries make trendy SoHo a top shopping destination, especially for out-of-towners. Known for its elegant cast-iron-facades and cobblestone streets, the neighborhood is also an atmospheric backdrop for fashionable crowds clustering at high-end restaurants and nightlife hotspots. During the day, street vendors sell everything from jewelry to original artwork.”

Yeah, not when I was working there, not initially, anyway.

First a bit of history:

New York City started out as a trading fort in lower Manhattan, originally settled by the Dutch, as most people know. It expanded northward after the British took over, with both Dutch and English farmers settling in the land above Canal Street, which was an actual (and fetid) canal. Fast forwarding, by the time the early 1800s rolled around, houses and streets were developed well into what is today’s Soho. Up until about 1850, this was a residential neighborhood, home to some of the most prosperous people in Manhattan. They made their fortunes in shipping, trade, banking and the like.

But by 1850, Broadway, which runs south to north through the middle of Soho, began to change. Up until then, it was a street of small shops and businesses, but modern times brought big changes. The first department store in America – A.T. Stewart’s “Marble Palace” opened down by City Hall in 1846, offering one-stop shopping for society’s ladies. As if overnight, Broadway, all the way up to Astor Place and above became a shopping and entertainment boulevard of delights, the beginning home of such familiar names as Lord & Taylor, Tiffany & Co. and more. They were joined by grand hotels, theaters and concert halls.

While the ladies were shopping and dining, the smaller streets behind the grand facades of Broadway were home to another kind of shopping. This was New York’s famous, or infamous Red-Light District. It was so popular that guidebooks were printed with descriptions of the different houses of ill repute and what they offered. Needless to say, this took the luster off living in the area, and wealthy people began moving to the next new neighborhood, further uptown. Middle class residents also began to move out, their homes taken up by small manufacturing companies and businesses. A few of those buildings are still there.

After the Civil War, this part of the city was recognized for its proximity to lower Manhattan’s piers, its ready wholesale customer base and the growing financial district. The price of land in Soho shot up exponentially. In the space of about twenty years, Broadway and the streets around it to the east and west were filled with large warehouse and factory buildings. While some were clad in brick, and some with a combination of brick and cast iron, most of the most striking had facades that were completely clad In metal, creating what today is the largest collection of cast-iron front buildings anywhere in the world. These buildings stretched from 14th Street and Union Square Park down to today’s Tribeca and to City Hall.

Soho was in the middle of it all and contains many of the best examples of this middle to late 19th century style of building. Technology in the form of large presses and sand-casting molds could take iron, zinc and other metals and mold them into architectural components. These companies could mold columns, lintels, pilasters, cornices, friezes and elaborate window frames, and apply them to what is essentially a brick box, creating ornate facades that could be painted to resemble limestone and marble. Humble warehouse space was transformed into rows of ornate and elegant palaces and it was done economically.

Because of the methods of construction, and the addition of cast iron, the fronts of the buildings were able to be filled with rows of windows, bringing in light and ventilation. The buildings were supported in the interior with a series of structural columns on each floor, generally in iron, which provided support for the large, floor-through empty spaces, perfect for storing tons of goods or rooms full of factory workers and equipment. The windows gave rise to all sorts of decorative elements incorporating fenestration as an important functional and decorative element. The first Otis passenger elevator in the world was installed in the 1857 Haughwout Building, originally a five story dry goods and department store, located on the corner of Broadway and Broome Street.

Another plus for cast iron cladding was that it was advertised as fire resistant, an important distinction in the days when buildings were lit by kerosene lamps and gas lighting. Fire in warehouses full of dry goods was a constant worry. The first cast iron buildings started to appear in the district in the late 1840s, designed in the popular Venetian Italianate and French Renaissance styles of the period. (The Houghwout was inspired by a Venetian Rennaisance-era library) By the end of the century, the buildings, both cast iron and otherwise, were expressing the much more elaborate and decorative motifs and design elements of the Neo-Grec, Romanesque Revival and various Renaissance Revival styles. A course on NYC architectural styles could be easily taught from just walking around Soho, Noho and Tribeca.

The area between Houston and Canal became the mercantile and dry goods district. The offices and warehouses belonged to some of the era’s finest silk, cotton, wool and lace manufacturers and importers in the nation. From these warehouses, products were shipped across the country to cities and shops big and small.

In addition to the fabrics themselves, known as dry goods, Soho’s warehouses and factories also manufactured furniture, print materials, and other light industry. The city’s garment factories were centered around Canal Street at that time, and greatly contributed goods for sale in Soho, as well. This entire area, top to bottom, was humming with prosperity, as well as industry and commerce, best illustrated by the size and quality of the buildings and their architecture.

As the city rolled into the 20th century, it was not the same old Manhattan. It was now part of Greater New York City, along with Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens and Staten Island. As fast as Soho grew and prospered throughout the latter half of the 19th century, it cratered just as fast as the 20th century progressed. Garment manufacture and wholesale fabric companies moved uptown to the west 30s up to 42nd Street, the trim and notions companies to the 30s on the eastern side of 6th Avenue. The fancy hotels, restaurants and theaters had already moved uptown to be closer to their audiences. In spite of a gradual exodus, new loft buildings were still going up in Soho, and these were even taller than the old ones. Elevator technology and engineering advances worked wonders. The new buildings were ornamented, as well, although the days of a full cladding was over.

But Soho, Noho and Tribeca, all full of five or more stories of open loft space were now not in favor. The area was more or less forgotten and unused except by companies, mostly wholesalers, that did not depend on street traffic. The streets were often empty, and whenver someone like Robert Moses got the idea to run a highway through lower Manhattan, this was where they wanted to put it.

While the large loft spaces were not condusive to the idea of office space, and manufacturing was leaving the city in waves, they were perfect for artists, who saw them as painting and sculpture studios, with room for large works, and most importantly, space to both live and work. And it was cheap. It was illegal to live in a loft at that time, they were not zoned residential and were not regulated by residential code or housing laws, but many landlords, who were sitting on unused real estate, began to secretly rent to artists.

By the time I was working in Soho, in the early 1980s, the neighborhood was beginning the changes that would turn it into what it is today – fancy retail shops, art galleries and super-expensive loft apartments. Most of the artists were on their way out to look for cheaper space in places like Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I was working for Rena Gill, who had a store called Victoria Falls on Spring Street between Wooster and West Broadway.

Most of the loft buildings in the very early 1980s still had industrial tenants. Many were in the textile waste business, bundling tons of fabric scraps and leftovers to be recycled and made into new fabrics or other uses. I used to walk around and see the huge blocks of fabric held together with strapping rolling out of loading docks onto trucks parked on the street. Although the garment district had shifted uptown, there were still clothing manufacturers and cutting rooms in Soho.

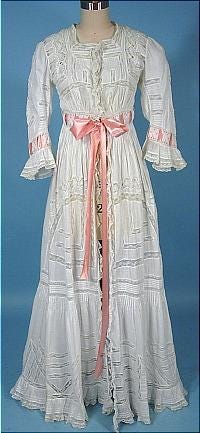

Victoria Falls was a store, a design workroom and a home. Rena’s business was divided between selling and altering authentic antique dresses and separates and using those original designs as inspiration for her own line of new clothing. Fashion at the time was very bohemian by today’s standards, and there was a large niche market of people who loved wearing antique clothing. Not the stuff from the 1950s, but the 1890s. Rena had dealers and pickers from all over the country buying Victorian and Edwardian clothing. She sold all kinds of garments, but specialized in whites: petticoats, bloomers, camisoles and dresses. Victoria Falls was at the forefront of this trend.

The white cotton and linen clothing, called “whites,” were usually liberally festooned with inset lace, ribbons and ruffles and were very popular for weddings. Customers would choose an antique dress and have it altered to fit. Generally speaking, only model-thin and shorter women could wear the clothing, as people 100 years ago were not as tall or as large as we are today. Victorian clothing was also sized to fit over corsets, which changes the shape of one’s body, so there were very few women who could simply put a dress on and walk out. There was a lot of recreating and alterations by Rena’s expert restorers. Starching and ironing some of these dresses could take a good hour or more, if it had a lot of fabric and ruffles.

The other half of her business was making Rena’s new line of clothing. She began her career doing this by copying antique pieces. The workroom had a closet full of the many kinds of laces, ribbons and fabrics, almost all white, for this operation. We made modern sized copies of Victorian-era camisoles, petticoats, bloomers and chemises, now worn as fashion, not underwear. By the time I started working there, she was also making dresses and separates, all based on historic designs. We made jackets, skirts, blouses and dresses out of plain and Liberty print cotton lawn, imported wool, linen and silk.

I was still studying voice and theater and had just left my job at Saks Fifth Avenue. I answered an ad in the Village Voice for someone with sewing experience to work in a small manufacturing space. I had never set foot in Soho before. Rena was specifically looking for someone detailed who could work with fine fabrics and trims. I was hired, and my first day was spent machine shirring miles of white cotton muslin which was going to be attached to the bottom of peignoirs. I met one of my closest friends there, she oversaw the preservation and alteration of antique garments. We’ve been friends for a long number of years, and still talk about the Victoria Falls days. In many ways, working there shaped a lot of what we both did career-wise.

After doing tasks like that for a while, I graduated into being the cutter. The current cutter was very pregnant, and I, who had never really done production work, suddenly found myself learning how to make markers and cut multiple layers when she couldn’t do it anymore. This was my first real job in the garment business. It was a great learning experience and we had a nice group of women working in the space, which was very limited, without natural light.

The only problem was that the former cutter was a tiny woman, at least eight inches shorter than I am, and the cutting table was built for her. After working on it for several months, I severely threw my back out. I was laid up for weeks, and had never experienced such pain in my life, as I did then. I’ve had lower back pain since, but nothing like what happened to me that day. All I did was bend over to pick up a piece of paper, and my back said, “I’m done, I’m going to kill you now.”

Our workroom was in the basement of the loft building, which was one of the smaller ones in the area. It was nice and deep, so we had more space than one might think, but as workspaces go, it was hardly ideal. One came down into the basement by means of a cast iron circular staircase, which could make bringing things up and downstairs really difficult. The stairs were located in the front of the store, in the only space allotted for window display, so the store windows always had to be designed with enough room to allow us to get up and down the stairs.

The ground floor retail space had really high ceilings, and a good sized loft space that was Rena’s office and her bedroom was built in the front, also only accessed by the cast iron staircase. Rena had a kitchen and shower down in the basement, in our shared workspace. The main selling floor had a large hatch in the floor in one corner that led to the basement by a wide set of stairs. That was how the sewing machines, bolts of fabric and other large equipment were taken downstairs. During store hours, the hatch was hidden by displays and clothes racks.

The day I threw out my back, it was impossible for me to go up the spiral stairs, I could barely move. I was laying on the cutting table and one of my co-workers who happened to also be a masseuse was working on my back. It only helped a little. I don’t remember how I got home, it must have been a cab or car service, as we didn’t have a car. I do know my brother came down to get me. There was no way I could have taken the subway.

Anyway, since I couldn’t go up the spiral staircase, they had to move the goods from the hatch on the selling floor and help me up the much wider and straight stairs. There were customers in the store when the hatch was opened, and I emerged from below, helped on both sides by Mark and someone else. There we were, rising into the light, from the pits of the cellar. It must have been wonderfully theatric, and I appreciate that, looking back.

Shoppers must have thought, “What the hell is going on down there?” If only I could have burst into song, something from Aida would have been appropriate. Or Orpheus in the Underworld. But I was barely standing hunched over and had a look of pure agony on my face, with white hot pain running up and down my lower back.

Drama would have to wait.

Wow, that is a great slice of NY life! Fascinating stuff!