(56th St. side of Carnegie Hall. The limestone entryway led to the elevators. Googlemaps)

My first voice teacher in NYC had a vocal studio in Carnegie Hall. OK, it was in the back of Carnegie Hall, and not affiliated in any way with the concert hall, except as a tenant/landlord situation. But still – my first teacher, Carnegie Hall… an auspicious start, right? The voice teacher, Chauncey Northern, had another personal connection, he had been my mother’s voice teacher, way back in the early 1940s.

Chauncey Northern was a tenor. He was born in 1902, in Hampton, Virginia and attended that city’s historic black college, the Hampton Institute, today a university. He and his brothers performed as the Northern Brothers Quartet, touring the country to raise money for the school, from which his parents and three brothers also graduated. In 1927, he composed an arrangement of the song, “Through Centuries Ringing,” which has since become Hampton’s official alma mater song. The Northern family is a big deal at Hampton.

(Chauncey Northern)

After graduating from Hampton, Northern came to NYC and studied at the Institute of Musical Art, which was later renamed the Juilliard School. He was from that generation of early 20th century black classical singers who broke color barriers around the world. He made his debut in the 1920s in Italy, one of the first to do so, singing the lead role of the tragic clown Canio in "Pagliacci'' at the Teatro Politeana in Naples.

In most operas, the romantic leads are generally written for tenors and sopranos. Mezzos are either the villainesses, servants, or sometimes teenage boys. Baritones and basses were usually authority figures, villains, or the best friend of the tenor. Black women who wished to have an operatic career had a hard time, a topic for another day, but being a black man, and a tenor to boot, was much harder. A black man singing a lead tenor role opposite a white soprano on an American stage was unthinkable when Northern was singing.

For much of the 20th century African Americans had to go to Europe to have a career and be cast in important leading roles. That has only changed within in my lifetime. Mr. Northern performed exclusively in Europe. In his first European tour, he gave a command performance for the king and queen of Spain and sang for Pope Pius IX. In 1937 he came back to NY and opened his Northern Vocal Arts Studio in Carnegie Hall. He was one of the few black voice teachers in the city and was a lifetime member of the National Association of Negro Musicians. By the time I started studying with him, he was in his late 70s, still going strong.

My mother found him in the same studio he had been in for the last 50 years. He remembered her, she was hard to forget, and I auditioned for him, and he took me as a student. I remember taking the elevator in the rear of the building, and going up to his studio, which had a small waiting room, leading to a larger room with windows facing out onto 56th Street. The other studios on that floor had voice, instrumental teachers and dance teachers. Students in tutus and tights roamed the halls, and music flowed from almost every door. It was a wonderful cacophony of music accompanied by the soft thump of feet dancing across the boards.

In the course of my weekly lessons, I heard many of his other students, all of whom were African American. Some of them were really good and he taught both men and women. I was studying with him for about six months, when he suggested that I audition for the Oratorio Society of NY. Several of his students were already members. He said that the Society was well established, had been around since 1873 and performed right downstairs in Carnegie Hall. They held auditions twice a year, always looking to swell their ranks with new singers. Belonging to it would make me a better musician, help me to learn some repertoire, and just have a good time making great music with other like-minded people in a very professional capacity. I auditioned and got in as a second soprano.

The Oratorio Society was my first introduction to the power of a wonderful professional chorus, up and coming soloists, a fine conductor and an orchestra, all performing in the greatest music hall in America. We had weekly rehearsals, off site, in preparation for the annual performance of Handel’s Messiah, plus one or more major sacred or secular works during the year. Some members had been with the Society for many years, while others were young singers like me.

The Oratorio Society had a strong connection to Carnegie Hall because they were instrumental in building it. Andrew Carnegie was the Oratorio Society’s fifth president, and in 1891, his fundraising initiatives, augmented by his fortune, resulted in the building of a magnificent performance hall for New York. Its first performance was conducted by composer and conductor Pyotr Tchaikovsky. The hall was later named after Carnegie.

As one could imagine, an organization with that kind of provenance attracted members of the upper crust in its early days. But over the course of the 20th century, they began to welcome singers from a much wider pool of applicants. Having great singers and fine musicians was more important than pedigree. When I joined, there weren’t a lot of minorities, but we were there, as chorus members, soloists and instrumentalists - African Americans, Asians, Hispanics and more.

Handel’s Messiah was a yearly treat. It was fun to sing and was certainly not an easy collection of music. A lot of professional singers sneer at Messiah, calling it tired and overdone, because everyone does excerpts or the whole thing in churches, singing societies, etc. Where would Christmas be without it? But, a good soloist can make a decent living singing it, and personally, I never got tired of it, it’s one of the greatest compositions in the history of Western music. Standing on the risers on the stage of Carnegie Hall, looking up into the rows of seats rising to the heights and singing is a feeling that must be experienced. I don’t care if you are there singing “Happy Birthday.” You are singing at Carnegie Hall!

I was with the Oratorio Society for about four years. We had a lot of great concerts, but by far, the most important and memorable performance for me during my tenure was in 1980, participating in the 80th birthday celebration for Aaron Copland, one of America’s most important composers. The concert consisted of a group of his works, both choral, orchestral and solo soprano songs, conducted by the composer himself and his good friend Leonard Bernstein. Copland and Bernstein on the same stage, conducting ME! You have no idea. OK, I was one member of the large chorus, but they conducted me, nonetheless. You can’t take it away from me.

(Aaron Copland in 1970, via Wikipedia)

Aaron Copland was a Jewish kid from Brooklyn who attended Boys High School in Bedford Stuyvesant. He studied composition in Paris under Nadia Boulanger and was influenced by the intellectual and musical community there. He came back to the US and wrote some of the most American music the 20th century would know. He was influenced by jazz and by the melodies and themes associated with the American Heartland and West. His best-known works are the music for the ballets Rodeo and Appalachian Spring and his symphonies. He wrote only one opera called The Tender Land, a story of Depression-era farm life, love, and family, which is filled with gorgeous music. And he wrote the pieces performed at this concert.

The Oratorio Society sang choral arrangements of his “Old American Songs,” conducted by our long-time conductor Lyndon Woodside. Soprano Linda Wall sang excerpts from his “Poems of Emily Dickenson,” conducted by the composer, and we surprised him with a rousing chorus of “Happy Birthday,” directed by Mr. Bernstein. And there was more.

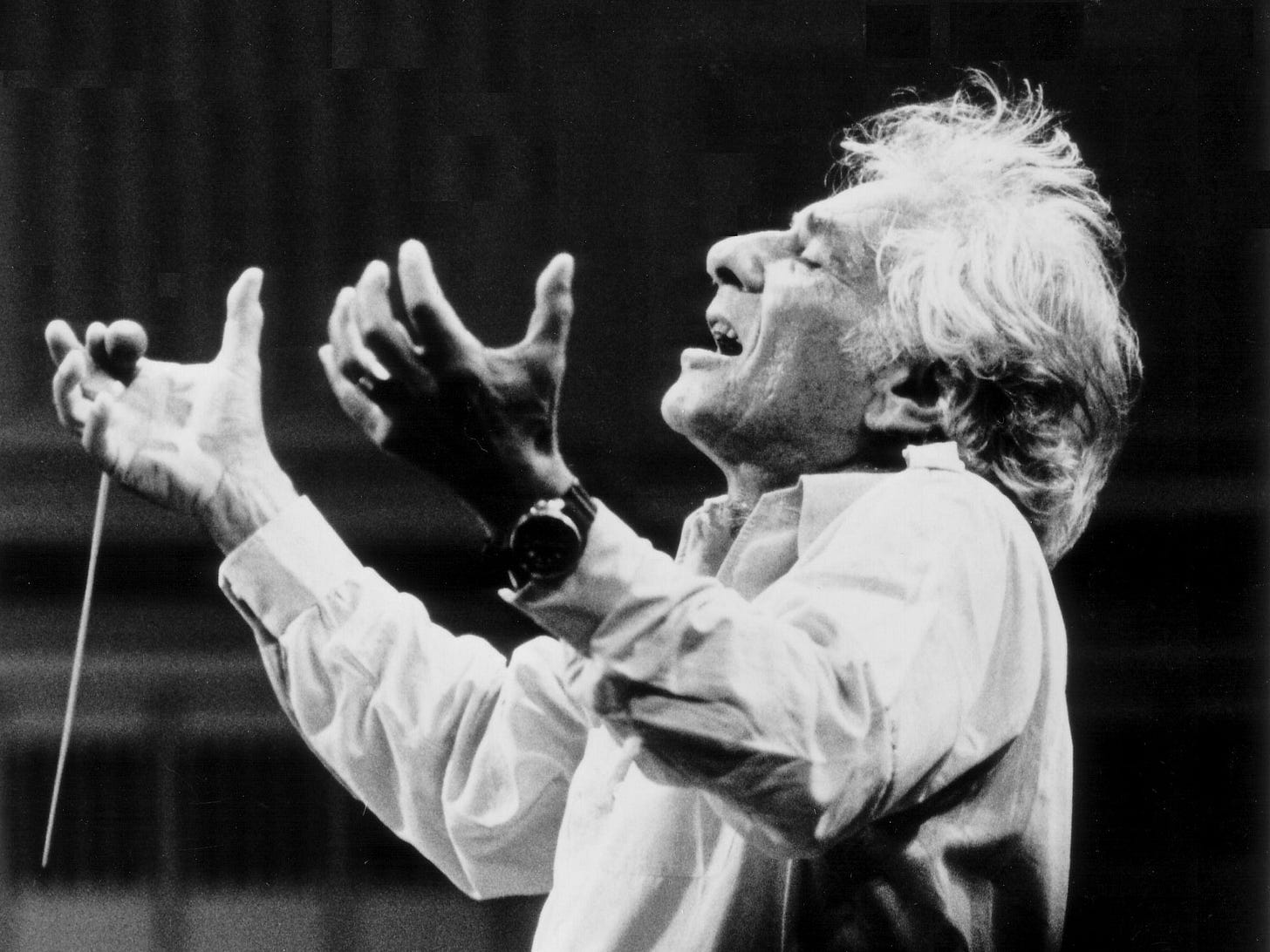

(Leonard Bernstein, via Leonard Bernstein Office)

Our dress rehearsal was the only time we worked directly with these genius composer/conductors before the performance and it was a memorable experience to be facing them. Generally, when one attended a concert being conducted by someone like Leonard Bernstein, the audience only sees his back, and only knows what he’s doing by watching his hands and listening to what those hands orchestrate. But sitting in front of him and watching him conduct was simply amazing.

First of all, if I had been a soloist, or orchestra member, I would have been terrified. “Lenny” was not a forgiving man. He expected nothing less than perfection, especially when it came to the basics, like counting the beats and playing or singing the notes as the composer wrote them. His talent came in taking perfection and polishing it, making 100% turn into 200%.

But God help you if you messed up. He snapped at people, was sarcastic, and impatient. If he didn’t actually vocalize his opinion, the look on his face said all you needed to know. The orchestra of very professional musicians was already good. No one made the same minor mistake twice. He had that ability to make his orchestra WANT to be better, because you wanted, no, you NEEDED him to be happy. When it was truly rocking, his face was a delightful expression of joy, as if he couldn’t believe that he got to be where he was, conducting such great music. It was awesome!

I was still a very young singer, and still had a lot to learn about classical music and classical repertoire. I was not that familiar with Copland’s music at that time. I was only familiar with his music for Rodeo, in part because themes from it were used in commercials for the beef industry, and with his Emily Dickenson songs, because I was learning them.

So, at the dress rehearsal, we practiced our pieces with the orchestra, and the soprano sang through hers. We were just sitting there when Bernstein got up to conduct the first piece of the second part of the Copland program. It was a short piece called “Fanfare for the Common Man.” I had never heard it before.

It starts out with tympani and trumpets, “bum, bum, bummmmmm,” the music swells, more horns and harmony are added, and more tympani and cymbals. It just gets more and more lush and majestic with just horns and percussion. It builds and builds and then climaxes. I could feel the hairs on the back of my neck and on my arms standing up. I was probably sitting there staring at Lenny and the orchestra with my mouth hanging open. I had never heard anything so majestically beautiful in my life. I didn’t want it to end.

A fanfare is basically intro music for important people. You’ve seen and heard them in countless movies. Someone important, like royalty, enters a space, and the horns trumpet their entrance with a short piece of music written just for them – their theme song, if you will, letting everyone know that they have arrived. Copland’s fanfare is not for kings and queens, it’s for us – the common man, a gorgeous piece of music that’s better than any royal fanfare. The music has been used in the Olympics and on other special ceremonial occasions and is one of the best-known American orchestral works ever. You have to listen to it:

The other work that Lenny was there to conduct was Copland’s symphony called the “Lincoln Portrait.” It is quintessentially American, with familiar musical themes throughout, and narration. Aaron Copland narrated his own work on this occasion. This too, is a gorgeous piece of music.

It’s hard to believe that during the Red Scare of the 1950s, Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn went after Copland, accusing him of not being a true American and a Communist because he lectured abroad and had a vast circle of suspicious lefty friends.

As a result, this piece, which had been slated to be performed at Eisenhower’s inauguration, was pulled at the last minute. McCarthy never listened to a note of Copland’s music, and it took an uproar from the musical community to convince the committee that they were going after a composer whose most familiar works were as American as one could get. Ironically, many of Copland’s works of this period were deemed too hoe-down folksy and pandering to the masses by some highbrow critics. You can’t win.

The concert celebrating Aaron Copland’s 80th birthday was wonderful. Carnegie Hall was packed, and the entire performance was simply perfect. Everyone performed to perfection. The horns pealed out the fanfare, as the drums beat the cadence. Tympani are tuned to different pitches, so it’s possible to play a simple melody on them. “Bum, bum, bummmmmm” on the drums and horns, a call and response. The audience went nuts. Most were probably familiar with the piece, but seeing the composer on the stage, and the orchestra conducted by the finest American conductor of the day was just the best.

“Lincoln Portrait” has some of the same themes and melodic harmonies as “Fanfare,” especially at the end. It is peppered with familiar folksong tunes, including “Camptown Races,” and is classic Copland. The narration is a short biography and excerpts of Lincoln’s writings andspeeches. It is very inspiring and powerful. I’ve included a link to a performance with Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic with African American bass-baritone William Warfield narrating. Good stuff.

William Warfield was the most prominent portrayer of “Porgy” in Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” in the 1950s and ‘60s. He and Leontyne Price, as Bess, were heard around the world in a State Department sponsored tour of the opera in Europe. They were even married for a time. Both were proving to the world that African Americans could not only sing opera, but they were damn good at it. Leontyne Price, of course, became a true diva – one of the finest classical singers ever, her glorious soprano soaring across the most important stages in the world, including many performances in Carnegie Hall.

She and Warfield may not have been as popular in Europe had it not been for singers like Chauncey Northern. He and others paved the way. From his studio on an upper floor in the rear of Carnegie Hall, he taught several generations of singers, including my mother and myself. I reached a point where studying with him was getting static, and I moved on, but I never forgot him. He was important, not only to my future progress, but to my pride and privilege of continuing a proud tradition of African American singers.

Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein both died in 1990. Copland was 90, and Bernstein was a much younger 78. Chauncy Northern outlived both and died at the age of 90 in 1992. Their contributions to music were enormous, and they were inspirations. Copland’s opera the Tender Land closes with an aria by Ma Moss, the mother of the family. I learned this piece years later, and it became a favorite, and one I auditioned with, when asked for a piece in English. The composition is very Copland, with lush, often dissonant orchestration, filled with pathos but ending with hope. Here’s a link: (there aren’t a lot of recordings of this, unfortunately. Start at 1:15 to 4:40 for the aria itself.)

As Ma says, and I still believe, “It’s just beginning.”

This is a wonderful, loving piece of writing on so many levels. It starts as a reminisce of young Spellen's music instruction in the back side of Carnegie Hall, but broadens into a love letter to the music form she studied and some of the remarkable figures she worked with, including Aaron Copeland, Leonard Bernstein and tenor Chauncey Northern who is given his due for helping open up the opera field to African American performers.

Lovely story, thanks!