Glenwood: The Titus Eddy Mansion

This Troy house is impressive, and the story behind it is pretty impressive too!

(Glenwood estate, now Administration building, Troy Housing Authority. Photo: Suzanne Spellen)

After settling into my new home in North Central, Troy, almost ten years ago, I began exploring my new neighborhood. As the leaves began to fall in autumn, a building appeared on the hill overlooking the neighborhood, near Oakwood Cemetery. It was best viewed from Glen Avenue, which formed a straight line up the hill from the Hudson River to the house.

From my vantage point on River Street, the building looked like an old mansion, a temple-front Greek Revival brick house standing high over the city. It was surrounded by the buildings making up Troy Housing Authority’s Martin Luther King Jr. Apartments.

Turns out, it’s one of Troy’s most important buildings, built for one of Troy’s most important families. Their legacy is not only important to the local area, but like many things that have come out of Troy, was important to the entire country. This is the story of the Eddy family, the family business, and their home - a mansion called “Glenwood.”

Titus Eddy – the family patriarch and genius

Titus Eddy was born in Weathersfield, Vermont on March 1, 1803, the son of Isaac Eddy and his first wife, Lucy Tarbell. Isaac was an engineer and an engraver. The family moved to Troy in 1826. Young Titus apprenticed as an engraver and printer under his father, but he soon became more interested in the ink than the printing.

At the age of 23, Titus bought some land near the Piscawan Kill, one of the city of Troy’s three main water sources. The Piscawan is the stream that runs through today’s Frear Park, under Middleburgh Avenue, and empties out into the Hudson.

By 1833, three different reservoirs had been created on the Piscawan, making it one of Troy’s major sources of fresh water. It would provide water to the city until the early 20th century, when the city switched to the Tomhannock system. This water would later be an important part of our story.

Eddy established a lamp black factory complex on this land, on a road that became known as Eddy’s Lane. The lane wound down the hill and connected Glen Avenue to Oakwood Avenue. He soon made another purchase, buying the land next to his holdings. This parcel would become his Glenwood estate. The entire Eddy holdings were about 120 acres.

Troy had many printing companies during the 19th century. Most of them were downtown. But Eddy had a product even more profitable and special than his printing skills. He had a formula for a special black ink that was superior to anything anyone else had.

Lamp black was one of the components in printing ink, and was also used for everything from shining shoes to blackening cast iron pots and stoves. It was a carbon by-product of a controlled burning of plants, oils, animal fats and bone. Eddy’s factory used several cooling huts into which the lightweight sooty carbon collected. This was then mixed with water and other ingredients to create a very black, indelible ink.

The ink was highly prized for high-quality printing. It didn’t smear, and as permanent as it gets for its day. It was so good, that news of the ink eventually made its way to Washington. When the US government first starting printing paper currency, during the Civil War, they did so with Titus’ ink.

The Eddy company held the contract for printer’s ink for the US Treasury’s Bureau of Engraving and Printing from 1861 until 1908. He also had the contract for the printing of US Government bonds and certificates. Titus manufactured a special yellow ink for printing gold certificates and a green ink for silver certificates.

It goes without saying that such formulas were precious, and Eddy was paranoid in their secrecy. He made the ink himself, from a secret formula that only he knew. He was so secretive about his ingredients that he would order them under false names and addresses, even purchasing ingredients that never made it into his formula, in case anyone was keeping tabs. The six workers he hired were not involved in the mixing of ingredients.

Two weeks a year, Titus locked himself in a room and made a year’s worth of ink for the US Treasury, fulfilling his $50,000 yearly contract. (Over $1.1 million today.) Access to Eddy’s Lane was restricted during this time, and soldiers from the Watervliet Arsenal were stationed at the factory to guard the manufacturing process, and take charge of the shipment. Local lore has it that Titus would emerge from his mixing room, covered in soot, but victorious.

The House and Estate

Titus Eddy became a very wealthy man in a growing city of wealth. He and his wife Anne Eliza had nine children. They all lived in a massive Greek Revival-style mansion that overlooked Troy, Lansingburgh and the Hudson River. It was a truly majestic view, perched high above the city. The house was built in the mid-1800s, probably in the early 1840s, and is one of the finest temple-front Greek Revival houses in Troy, and today, one of the few surviving large mansions that once overlooked the city.

The large house is comprised of a 2 ½ story central red brick house, with a large

T-shaped extension in the back, which forms a courtyard. Three sides of the extension are porched in. The front façade is most impressive, with a large Ionic portico supported by four large fluted columns, all in white painted wood.

Glenwood was a typical farming estate of its day. The farm raised cattle, both dairy and beef, horses, pigs and fowl, and grew oats, wheat, rye, barley and vegetable crops. Eddy had his own mill, ponds and water from the Piscawan Kill, woodlands and fields. The 1850 census also reveals that the estate employed six farm laborers and house servants.

Meanwhile, water issues arose. Troy’s water flowed to the city from the Piscawan reservoirs by gravity, and the Eddy estate was in the way. In 1882, the City of Troy voted to deny the Eddy estate access to the water. But that decision was declared “premature and ill-advised” and rescinded. In 1883, the city built two new collection ponds, put in a new series of pipes and cut the estate off. They had to pay the Eddy family thousands of dollars in return. The estate was able to get their water from another source, probably an underground stream of the Piscawan.

Titus Eddy died on February 6, 1875. He’s buried in Oakwood Cemetery, along with other family members. Before his death, he shared his secret formulas with his son James Albert, born in 1833. James took over the business, and was the only other person on earth who knew the Eddy ink formula. He grew the business, and vastly increased the family fortune over the course of the end of the 19th, and into the 20th century. James ran the company successfully until his own death in 1918. The secret formula died with him. To this day, with all the chemical analysis expertise we have, the exact formula remains elusive.

The Eddy Legacy

James married Elizabeth Hart Shields. Her mother was a member of Troy’s influential and wealthy Hart family. James had a twin brother Titus, who matriculated with him at RPI. He became a druggist and chemist, and left Troy with his wife and moved to Manhattan. One of James and Titus’ sisters, Anna Eliza, married David Johnston, the son of Robert Johnston, the powerful manager of Harmony Mills of Cohoes. David worked as Superintendent of the Mills until the early 20th century.

Another Eddy daughter, Eliza, married Edwin Frear, brother of William Frear, founder of Frear’s Troy Cash Bazaar. Two of the other sisters, Elizabeth and Maria, never married, and lived at Glenwood most of their lives. Other siblings also left the estate, some stayed in Troy, others moved on. Titus’ wife, Ann Eliza, died in 1887, and shares a monument in Oakwood with her husband.

James and Elizabeth Eddy were generous people, donating to many of Troy’s charities and worthy causes. In 1925, several years after James Eddy’s death, Elizabeth and her daughter Ruth Hart Eddy established the James A. Eddy Foundation, which led to the building of a nursing home, and eventually, the establishment of all the Eddy senior facilities, rehab centers and agencies we have in Troy and the Capital Region today – a wonderful legacy for any ink maker.

Glenwood Moves into the Future

In 1940, the Eddy family donated the Glenwood estate to Russell Sage College for use as an auxiliary campus. A majority of the land had been sold off over the last century, leaving the house, surrounding buildings and 36 acres. The women’s college was already using the grounds to stable their horses, and had established a large horse paddock and bridle paths. The school planned to use the estate mainly as an athletics campus, with tennis courts, sports fields and a possible swimming pool. The house would be used for events and as a guest house.

In addition to the house, Russell Sage also got title to the out-buildings on the estate, including the ink factory building, which was a large red brick building which stood near the creek running near Eddy’s Lane. After the company closed, the building was used as storage by the estate. On August 4, 1941, a fire started in the abandoned building, gutting it.

Firemen found 40 barrels of charcoal in the ruins, material used in manufacturing the ink. It was thought that the charcoal had spontaneously combusted, causing the fire. The last vestiges of the Eddy ink making process was gone. Because of this fire, as well as other vandalism to the property, Eddy Lane was closed to the public. There would no longer be a public road joining Oakwood to Glen Avenue.

Russell Sage divested itself of the Eddy property, selling it to the City of Troy. The Troy Housing Authority Administration offices moved from City Hall to the property when the Martin Luther King Apartments were built in 1970-71. The original plans were to place the offices in the house as well as renovate space for four apartments. Today, the THA uses the entire building complex for offices and conference/ classroom/gathering space.

The house was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. At the time, it was one of only two such designations in the City of Troy. Today, most of downtown, as well as many individual buildings have National Register designation.

From time to time, the THA opens Glenwood for public tours. Only a few of the original features of the house remain, but they are impressive, as is the view from the hill. Photographs of the family, of Russell Sage students and other memorabilia remain in the executive offices. Much more should be done to share this important part of Troy’s history and architecture with the public.

*

(Titus Eddy, painted by Oliver Tarbell Eddy, portrait at the Bennington Museum, Vt.)

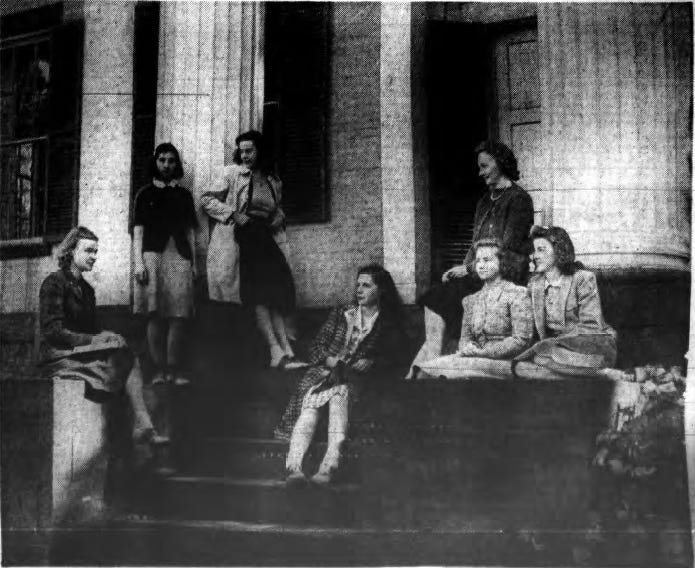

(Russell Sage students at Glenwood. Troy Times Union paper, 1940)

I loved reading your article and seeing the photos, Suzanne. I was a student at Russell Sage College from 1967-71 when we still went to Glenwood for class activities. Photos of my class there appear in our yearbook. When my husband and I bought our first house in Lansingburgh in 1980, I realized that Glenwood had been turned over to the Troy Housing Authority. It was hard to accept, since I had been there when it was such a beautiful building and site. About five years ago, I was delighted to take a tour of the house at Michael Barrett's suggestion. I didn't remember being inside while a student, so it was exciting to see the interior. I'm glad that Glenwood still stands and is being cared for. Do you have any photos of other large historic buildings that were on the hill but demolished?

Great article. I'm surprised James let the ink recipe die with him, what a shame! You give his death as both 1918 and 1925, which is correct?