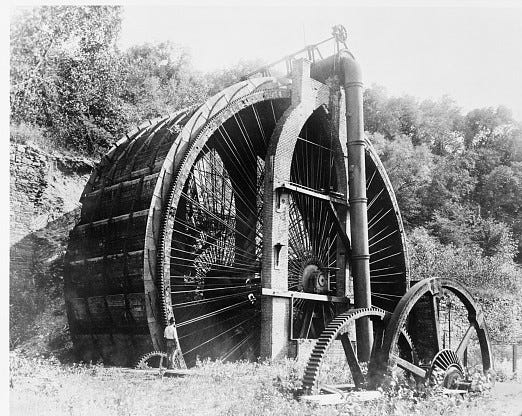

1907 photograph of the Burden water wheel, taken seven years after it had been abandoned. Note the scale. There’s a man standing at the left side of the wheel.

If you’ve ever ridden on a Ferris Wheel, then you have a connection to Troy, NY. Because the inventor of that iconic amusement park ride, George Washington Gale Ferris Jr., was an 1881 graduate of Troy’s Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), and no doubt was influenced by one of Troy’s most impressive industrial monuments – the Burden Water Wheel.

Henry Burden, a Scottish immigrant, was a mechanical-minded wonder himself. Over the course of his lifetime, he invented many different machines and ways of production that propelled his Burden Ironworks into the forefront of 19th century manufacturing. His factory was a huge operation in South Troy, employing over a thousand men and boys, especially during the Civil War years.

Burden came to Troy in 1822, as superintendent of the Troy Iron and Nail Factory. When he arrived, nails were being forged, one at a time. By 1825, he had patented a machine that made wrought iron nails and spikes at an unheard-of rate, eliminating expensive handmade nails. Over the next decade, he took over Troy Iron and Nail, changed the name to H. Burden & Sons, and started making expansion plans.

In 1835, Burden invented the first of his horseshoe making machines. He would improve upon it with three more patents before 1862. Making horseshoes put Burden Ironworks and Troy on the map, issuing in an entirely new industry. Burden’s machine was hailed as one of the technical marvels of its time. His machine could make 3,600 horseshoes per hour, without any human touch. This was huge and game-changing. The 19th century world ran on horsepower and horses were shod for their own protection. Before Burden, blacksmiths bent iron bars and shaped the shoes one by one.

By the early 1850s, Burden was the largest manufacturer of horseshoes in America, with the rights to his machine technology sold to an English company for their use. Wars in Europe and American expansion out west gave him more and more customers, so that by 1851, Burden needed more power to drive his mills. His factory was located on a high slope along the Wynantskill Creek, which flowed into the Hudson River.

Inspired by similar Scottish waterworks, Burden built his waterwheel in 1851. It was 62 feet in diameter, 60 feet tall, and 22 feet wide. The entire thing was made of steel, except for the buckets and drum wheel. It was suspended by iron rods over the Wynantskill. The wheel turned day and night, weighed 250 tons, and could produce 500 horsepower when spinning 2.5 times per minute. To get more water power from it, Burden built a series of reservoirs along the creek, which held water to increase the supply and pressure.

The wheel was instrumental in further growth of Burden’s business, as was the Civil War. When the Union Army went to war, its horses and mules walked on Burden horseshoes. Burden made a fortune. He funneled much of his income back into the mill, building another industrial complex closer to the river, and a new company headquarters.

The “Upper Works,” the first factory, and the wheel, were joined by the “Lower Works,” the steam mills next to the Hudson River. Between the two sites, Burden had 60 puddling furnaces, 20 heating furnaces, 14 trains of rolls, three rotary squeezers, nine horseshoe machines, twelve rivet machines which each produced eighty rivets a minute, ten large and fifteen small steam engines, seventy boilers, and the water wheel.

Because of Troy’s location on the Hudson River, near the Erie Canal, Burden was able to both receive the raw materials he needed for his forges, and send his goods out along the river and railroads that ran just beyond his doors. The growth and importance of his company made him one of Troy’s largest employers. At their height, they employed over 1,400 men, a full eighth of Troy’s population. Their primary products were horseshoes, railroad spikes and rivets.

Henry Burden died in 1871. His wife Helen had passed away in 1860. The couple had eight children, five boys and three girls. The running of the company passed on to the male heirs. Two of the sons, James and I. Townsend Burden were running the company by the time Henry died. James inherited his father’s inventiveness and business acumen.

In 1881, the sons reorganized H. Burden & Sons as the Burden Iron Company. The brothers built a handsome new office building for the company that year, near the railroad tracks of the Lower Plant. James got a larger share and more control of the running of the company, although both brothers, as well as other family members now called NYC home. I. Townsend especially enjoyed living in the city, and was counted one of the “400,” the group of prominent wealthy New Yorkers at the top of the society world.

Unfortunately, Burden Ironworks did not remain at the top of the industrial world. As the century wound down, so did business. The brothers disagreed on everything, law suits resulted, and while they were arguing, the iron industry moved out of Troy, to locations where coal and raw materials were closer and more plentiful.

The Upper Works, running on water power in the age of steam, was soon obsolete. By 1900, the plant was abandoned as the business consolidated to the Lower Works, which ran on steam. In only a matter of years, the large industrial park was demolished and/or abandoned.

But tourists and locals still visited the famous waterwheel, taking photographs sitting on the spokes, or leaning against the wall. Postcards depicted the site, with the gear mechanisms upended and rusting, while crumbling walls overgrown with vegetation gave the scene a romantic ruin look. It made for a great photo but represented the end of an era. Eventually, the metal was further dismantled and sold for scrap. It was a good think Henry Burden didn’t live to see it.

The brothers, and their sons and nephews who followed them tried to revive the business, by moving into other products and streamlining. They began manufacturing coke, gas and pig iron. But they didn’t have the drive and inventiveness of Henry Burden and were operating in a rapidly changing 20th century world. They built a blast furnace for the plant in 1925.

But by 1934, the company went bankrupt, and into receivership. The Republic Steel Corporation bought the company assets in 1940, with an interest primarily on the blast furnace. They tore down most of the other buildings and made the office building a storage site. It was emptied of records, which all went to the State Library in Albany. The office building’s fine cherry wainscoting was removed and sent to corporate HQ in Cleveland.

Republic kept the blast furnace going until 1969, and the rest of the company until 1972. The end of Troy’s iron industry mirrored the losses in its textile industry as well, as the city joined rust belt industrial cities across the nation in economic and social decline. The decay and abandonment of buildings reflected the loss of jobs and urban disinvestment.

Today, the Burden Ironworks headquarters, now the Hudson Mohawk Industrial Gateway Museum and Burden’s Woodside Church and Chapel, now a residential arts center, are the only visible remnants of Henry Burden’s vast ironworks. Burden Pond and the retaining pools Henry Burden built still exist, but they too are subject to the decay and ravages of time.

Burden’s impressive waterwheel today is still a Troy icon. A mural of the wheel greets motorists coming into South Troy. But there is no wheel, or even parts of it. As a city, over the century, Troy has missed multiple opportunities to preserve its industrial, architectural and historic heritage. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. Of course, you can’t keep everything, but someone should have kept that wheel.

(Full disclosure, I am on the board of the Hudson Mohawk Industrial Gateway. We chronicle and seek to identify and preserve the huge and impressive legacy of industry in the Capital Region. America’s Industrial Revolution started here!)

https://hudsonmohawkgateway.org/