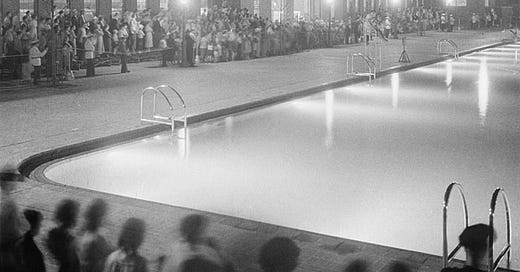

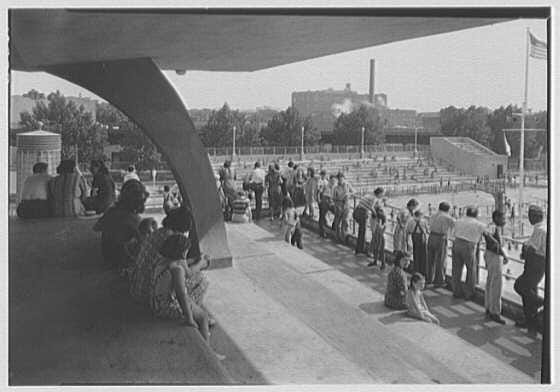

(Dedication of the Sunset Park pool, Brooklyn. 1936 via NYC Parks Dept.)

(This story was originally published on Brownstoner.com in 2011.)

“Hot time, summer in the city” has been New York’s theme music for a long time. Part One of this story was told a couple of weeks ago, outlining the New York City public baths, that lifeline of cleanliness and relief that was, far too often, all the poor of the city had. From the floating baths on the East River, to the ornate public baths built across the city, the fledgling movement toward public health standards began with the notion of clean running water that one could submerge their entire body in.

But the building of the great public bath houses in the first two decades of the 20th century came too late for them to be utilized in their original capacity by the “great unwashed”. By the time most of the bath houses were completed, the tenement laws had been changed and upgraded, so that running water and bathtubs in tenement houses were mandated by law. Almost all of the grand bathhouses in lower Manhattan were re-commissioned by the WPA and through the Parks Department programs instituted by Robert Moses.

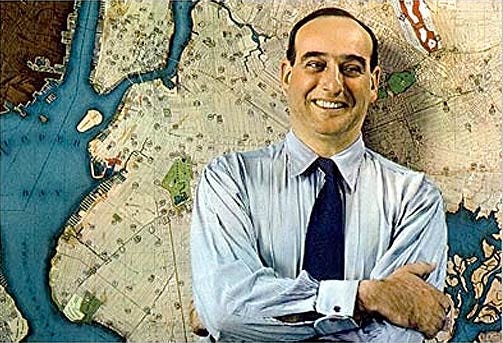

Surely one of the most controversial figures in 20th century New York, Robert Moses changed the face of the city like no one before, or since. He was appointed as Parks Commissioner by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in January of 1934, in the midst of the Great Depression. By that July, he had plans on the table to build 23 pools across the city, including six in Brooklyn.

(Robert Moses in 1938. Photo: Archpaper)

By the 1930s, swimming pools were a common feature in the city’s YMCAs, and other youth and fitness clubs. They were also commonplace in the amusement parks of Coney Island. You could swim at places like the Hotel St. George, in Brooklyn Heights, which had a world-famous pool. But for all these watery wonders, you needed to have money. For most of them, you also had to be white, but more on that later.

Poor people did not have free access to swimming pools. Many were still seeking relief in the polluted and dangerous waters of our rivers and bays. Robert Moses believed that parks and recreation centers were an important part of city life. The earlier Progressive Movement of the beginning of the 20th century advocated parks and play areas as necessary for the well-being of poor and immigrant children. Moses would take it one step further.

The role of children in American society had changed since the dawn of the 20th century. Reformers had successfully advocated for the right of children to have a childhood. They were not small adults, nor were they merely labor fodder for factories or farms. By the time of the Great Depression, the federal government had taken responsibility for the social welfare of children.

Children were now expected to stay in school until the end of high school, and their childhoods were supposed to be dedicated to education and play, not work. In large cities like New York, that meant that more facilities were needed for children: more schools, parks, recreation centers and outdoor recreation facilities. The Parks Department had a whole lot of building to do.

The New Deal was the Great Depression’s stimulus package. The basic premise was to help work America out of the Depression with infrastructure and new public works projects. Millions of federal dollars were given to cities to build all kinds of things, including highways, parks, recreation centers, and yes, swimming pools. Working with the Works Progress Administration (WPA), funds were acquired by LaGuardia and Moses in 1934, to build the largest and best pool project in America.

(Betsy Head Pool in Brownsville, Brooklyn - 1937. Photo: NYC Parks)

Thousands of kids learned to swim in city pools, beginning in 1934, with a well-publicized Learn to Swim program run by the Parks Department, expanded with WPA funds. Because of these funds, the city was able to have eleven large pool complexes ready for opening in the summer of 1936. That summer was particularly hot, and kids and adults alike were lined up for blocks each time a new public swimming pool opened. And what great pools they were!

The WPA pools were masterpieces of public recreational architecture and engineering. They utilized state of the art technologies. They were designed with elaborate underground piping systems, which heated, filtered and chlorinated tons of water before piping it into or out of the system. The design team was led by architect Aymar Embury, II, a prominent Manhattan architect and scholar, and landscape architect Gilmore D. Clarke.

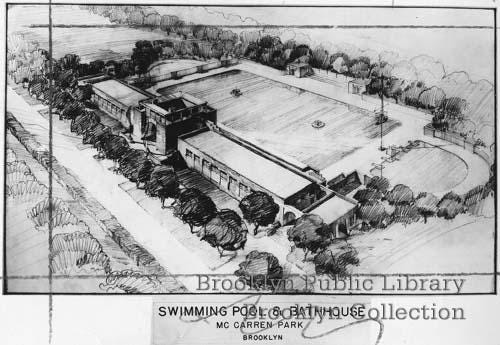

(Plans for McCarren Pool, 1936. Via Brooklyn Public Library)

The powerful Parks Department worked out of the old Arsenal, in Central Park, where Moses, Embury, Clarke and their staff of 1,800 planned and executed one of the most impressive programs in public recreation ever.

In Brooklyn, they built four recreation and pool complexes in 1936: Williamsburg’s McCarren Pool, which could accommodate 6,800 bathers at a time. Red Hook, which had an opening crowd of 40,000 people. Sunset Pool, in Sunset Park, boasted an underwater lighting system. Fiorello LaGuardia flipped the switch at the opening ceremonies on July 20, 1936. And lastly, the Betsy Head Pool, in Brownsville, which opened on August 6th, and had to be rebuilt after a 1937 fire. All these pools are still in operation today, although they all closed at some point, often for years, for necessary renovation and repair.

In addition to these new recreational centers and pools, many of the old bathhouses were also converted. In Manhattan, six of the indoor pools in bathhouses were revamped by WPA money in 1940. The floating bath pools were continued until the end of the 1930’s. And by the 1950’s, Brooklyn got a new indoor pool facility in Brownsville, and the St. John’s Recreation Center was built in Crown Heights. By 1964, the city had 17 outdoor pools and 12 indoor pools, for a grand total of 29.

Robert Moses himself was an avid swimmer and had been a valuable member of his Yale University swim team. He would swim for exercise and pleasure his entire life. Perhaps that explains why pools and recreation centers were so important to him. Not coincidentally, all these centers were in a working class or a poor neighborhood, which has to bring up the ever-present specter of race and class in Depression-era New York City.

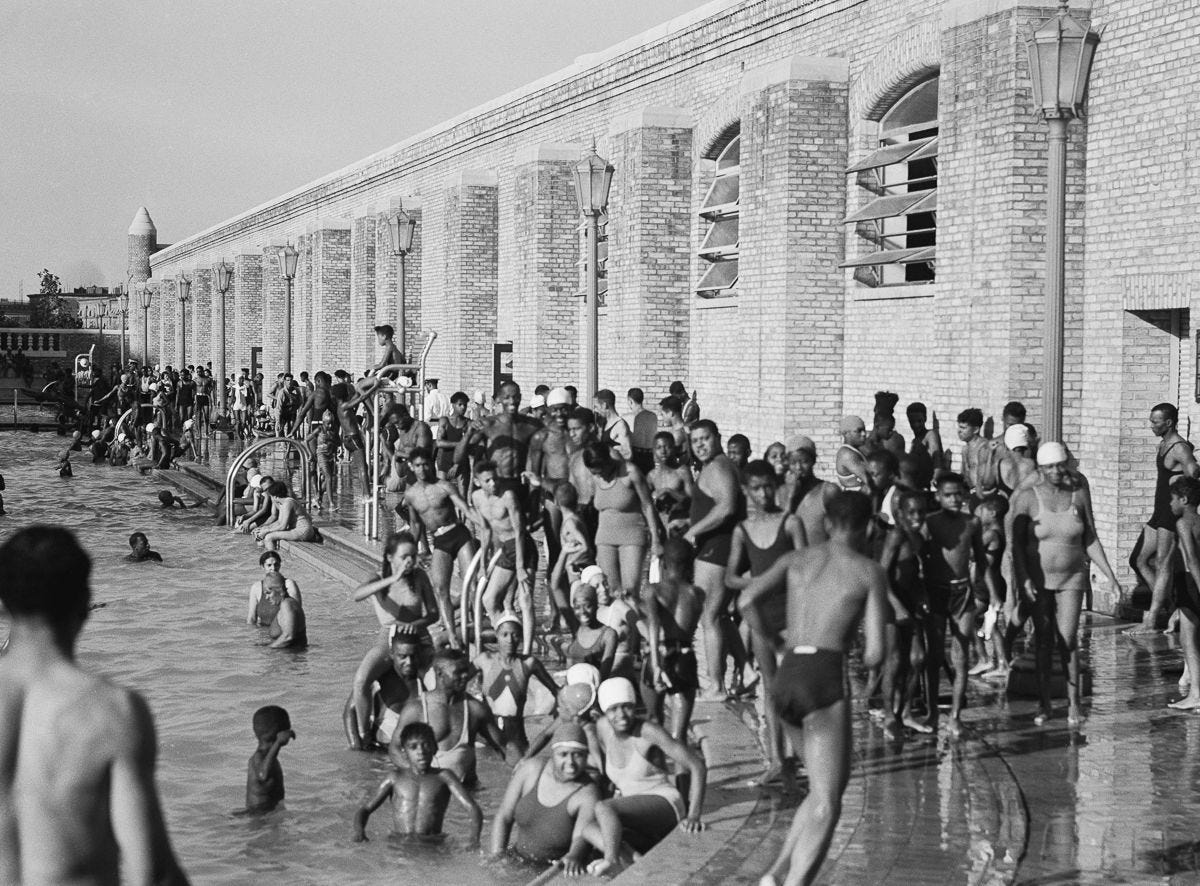

(Red Hook Pool, 1937. Photo: NYC Parks)

We most often see photographs of happy splashing crowds of white children and adults in the pictures of the WPA pools. Sometimes we also see photos of black or Hispanic kids in a pool in Harlem or Brownsville, but we rarely see black and white kids together. Asian kids are non-existent. Was segregation going on in the liberal North?

The official position of New York City government has long been that everyone was equal, but everyone always knew that was not the case. Racial and ethnic groups in the city have always been marginalized, and the politics of pools would be no different. According to an excellent article called “Race, Place and Play – Robert Moses and the WPA Swimming Pools in New York City”, by Marta Gutman, Moses was a racial traditionalist who believed in the practicality of “separate but equal”.

Scholars have theorized that the years between World War I and II, when European immigration was way down, and immigration and migration of Caribbean and Southern American blacks was up, gave rise to New Yorkers’ fixation with matters of color over ethnicity: black and white, bad and good, poor and not-so-poor. Things were clear, and simple. But were they?

Recreation was a mess in traditional black neighborhoods, as funds were not equally allocated for playgrounds, parks, pools, or athletic fields. Central Harlem, home to New York’s largest black population, had none of these facilities at all in the 1920s and early ‘30s. Studies at the time showed that the high rate of illiteracy, disease and delinquency among black youth was in part due to the fact that there was no outlet for public recreation.

Although not as bad as Central Harlem, Brownsville and East Harlem also suffered from a lack of facilities. African-American community leaders began to pressure the city to build adequate and equal recreational facilities in these communities as well. Playgrounds were one thing, but nothing riled people up like swimming pools.

(McCarren Park, 1940. Photo: NYC Parks)

Swimming pools were expensive, and very desirable. They were also places where boys and girls mixed socially, and where children and adults, in the new revealing swimsuits of the day, were exposed to nearly naked flesh, both in and out of the pool. This brought out the worst in racist, sexist, and class biased attitudes and behavior. When told they would have to integrate their pools, many white operators protested that the water would have to be drained, and the pools scrubbed and filled with fresh water after black children swam in them. Other protests arose over “race mixing”, and the horrors of interracial dating or sex.

And it wasn’t just race, but also class. Many parents worried about the perversion of having working class youths in proximity of teen aged girls, who were approaching womanhood. There was a fear that boys, who traditionally went swimming in the nude, would not wear trunks, or behave appropriately. Data showed that many parents kept their daughters away from public pools. Most swimmers in all of the period photographs, regardless of race, are male.

There was also the danger of disease. Before Robert Moses’ WPA pools, most city pools were not cleaned regularly, and poor children who played in dirty streets and swam in the filthy waters of New York City’s rivers and bays, also jumped eagerly into city pools, spreading polio and typhoid, in those days before vaccinations. By the time Moses took over a unified parks system in 1934, it was time for widespread change. In a massive building campaign, he built eleven state-of-the-art pools in two years.

Some were in predominantly white neighborhoods, some in black. They were essentially separate, but pretty much equal. In East Harlem, the Jefferson Park pool was almost exclusively white Italian. Black swimmers did not go there, and Puerto Ricans, who were beginning to edge Italians out of East Harlem, were also not welcome. When the Central Harlem Colonial Pool was opened, also in 1936, it became the “black pool”, and the place where the Puerto Rican kids were more welcomed.

(Colonial Park Pool, Harlem (now Jackie Robinson Pool). Photo: NYC Parks)

Robert Moses did not feel it was his place to integrate either place, and because the facilities were equal, he was happy and had done his job. He said, in a speech at Harvard, in 1939, “Immediately on the opening of the new pool it became evident the local Italian population would not tolerate the so-called Spanish element in the pool. Obviously this was against the spirit and the letter of the State Constitution and the Civil Rights Law, yet what could be done about it?...Shortly after this pool opened another one in the Negro section was completed. The Porto Ricans [sic] finally decided to go there. The Harlem Negroes were resentful of any white intrusion. Our problem was ended in a practical way and the theory of the Bill of Rights remained intact.”

The integration of community pools would have its moment in the Brownsville pool at Betsy Head Park. In that neighborhood, the traditional Jewish neighborhood was quickly making way for a large population of black people. There was already a recreation center here, with a pool, but it had not been kept up, and was in Moses’ words, “disgraceful”. The Parks Department began a series of improvements, and when the pool re-opened in the summer of 1936, no one from the mayor’s office or the Parks Department even bothered to show up. The snub was shrugged off, but the slight was unheard of.

Moses promised to do some more fixing up, but a mysterious fire gutted the entire site in 1937, causing the entire project to be rebuilt. Moses wanted to use the new funds allocated to NYCHA to rebuild the park, arguing that recreation centers helped to build communities. He didn’t get control of NYCHA funds, but the new Betsy Head pool and recreation center opened in 1939.

Unwritten rules encouraged self-imposed segregation at this pool, with Jewish and black residents using it at separate times. A film of the opening day shows only whites using the pool, and these were run in the Architectural Record and in newspapers. But photographs taken that day and subsequently, never published, show a different story. In these photographs, blacks and whites, boys and girls, using the pool together.

(Betsy Head Pool, 1939. NYC Parks)

The photographs, by Samuel Gottscho, show young women and their immigrant mothers and grandmothers outside of the pool enclosure, the girls in their fashionable bathing suits, and the older women in more conservative dress. He shows an immigrant community becoming “American”. He also shows black and white children sharing locker rooms, the pool deck and the water. As time passed, boundaries lowered. Team sports for boys, organized at the centers were integrated without incident, and African-American lifeguards were employed at Brownsville, and also at McCarren Park in Williamsburg, as well as in Harlem. This was New York, in the 1930s and 1940s. Maybe not great progress and equality, but certainly a start.

This was in sharp contrast to an incident in St. Louis, where the integration of a city pool in 1941 led to a riot, with white rioters chasing black people through the streets, clubbing them with bats and lead pipes. 400 policemen were not able to stop the riot, and the mayor of the city re-instated segregation in the city’s public pools, a policy that wasn’t overturned for another twenty years.

We never got that bad in NYC, thank goodness. Long story long, the story of race, segregation and neighborhoods in New York City is a long tale, fraught with moments of great stupidity on all sides, as well as moments of great courage. Robert Moses may not have helped the cause of integration, but he didn’t invent segregation or discrimination, either. He did build some damn fine pools. Love him or hate him, you have to give him that.

As a kid from Queens, we went to Astoria Park and pool. I think it must have been another WPA pool. Google lists it and Betsy Head pool as both being 330 ft. x 165 ft. That can't be a coincidence. The most impressive thing about Astoria pool is that it is framed by the Hellgate Bridge on one side and the Triborough on the other. Photos are dramatic. https://www.yelp.com/biz/astoria-park-pool-astoria

My takeaway from Caro's book was that Moses' Parks Dept legacy was mostly positive, in contrast to his TBA and Planning Commission debacles.