Knights of the Silent Steed: the Life and Times of the Kings County Wheelmen

Bicycling is as popular today as it was when the public first embraced it in the 1890s.

The bicycle has been a part of most of our childhoods, going back generations. If you grew up in a small town, in the country, or a suburb, chances are you spent your childhood on a bicycle. Many city kids also learned to ride at a young age. But for the late Victorians, cycling was a relatively new phenomenon, and most people learned to ride as adults.

Something special happened because of the bicycle. Cycling was one of the few recreational activities that men and women could both take part in. They could ride together, and for the first time in memory, a modern single woman could ride the streets by herself, unaccompanied by chaperone or suitable male companion. For that reason alone, the sport changed society.

While pictures of mustachioed men in striped shirts and caps on enormous high wheeler cycles are in the popular imagination for this period, the truth is that by 1898, the bicycle of the day looked pretty much the same then as it does now. The frames, seats and pedals haven’t changed much in the last hundred years. By this time, bikes had inflatable rubber wheels, and a repair kit was a must have for any serious rider, as the roads and streets could be pretty atrocious. Bikes even had head lamps for riding at night, mounted on the frame between the handlebars.

A good bike cost between $25 and $50, making it affordable to the middle classes. A host of manufacturers produced fixed gear bikes, which were the standard, as well as early multi-geared racing bikes.

In addition to standard bikes, there were specialty bikes of all kinds. Tandem cycles were very popular for couples, but they also made multi-seat racers that held up to six riders. There were bikes that pulled baby carriages and bikes for all kinds of work situations, with carts and hanging attachments. The Victorians were a very social bunch, and loved getting together in organizations, so it didn’t take long for bicycle clubs of all kinds to spring up all over the country.

During the last two decades of the 19th century, there were no cooler men on earth than the members of the Kings County Wheelman’s Club of Brooklyn. They were like rock stars and the US Olympics Men’s Gymnastic Team rolled into one; a collection of men’s men, envied by their fellows, gushed over by young ladies and star-struck reporters alike, one of whom called them the intrepid “Knights of the Silent Steed.” They were Brooklyn’s best and most famous amateur bicycle club.

The Kings County Wheelmen were among the earliest clubs to organize in Brooklyn. They first came together as a group of 25 cyclists from the Eastern District, that part of town that included Bushwick, Williamsburg and parts of Eastern Bedford. They were established in 1881 and began having meetings in rented rooms in a hall in Williamsburg in 1882.

They were all affluent young men, many graduates of elite colleges and members of other sports clubs. They had taken to biking the way a duck takes to water and wanted to organize to plan biking trips and other social activities, but mostly, to put together a racing team and go out there and kick butt. Some cycling clubs just planned short outings for health and recreation. These guys were not as interested in that. Like extreme sports enthusiasts today, they wanted to take bicycling as far as it could go at the time, and that meant marathon bike trips upstate to Saratoga or to Montauk and back, exhibition trick riding and racing.

They soon did all three. The club’s best members were soon household names as the KCW racing team became the best in the city, taking on all comers. They raced other Brooklyn bicycle clubs, Manhattan and Long Island clubs, and the clubs affiliated with Ivy League colleges and other upscale schools. The Brooklyn papers were full of their exploits, writing about races won, records broken, and interviews with the stars of the team.

They participated in parades doing synchronized riding, weaving in and out amongst themselves, with colorful silk outfits, sometimes carrying torches or other impressive props. They also staged riding shows at local arenas and venues, impressing the audience with wheelies, summersaults and circus riding tricks like doing headstands on the seat. The Wheelmen were fearless and for most of Brooklyn, especially the young and social minded, they were simply gods.

All the elite wheelmen’s clubs shared a love of showing off. Like a peacock, a professional racing biker was resplendent in his club’s silks, the brightly colored uniform he wore in races. It was a tight-fitting outfit carefully designed to cut wind resistance and increase speed. The costumes also served to give the young ladies quite a view of the rider’s ability to father children.

When they weren’t being sports heroes, the Wheelmen were a great bunch of guys. They met at their rented quarters and played cards, probably drank like fish, and smoked cigars. Of course, everyone who was anyone wanted to join, and the ranks of the club grew to the point that the rented rooms were not large enough. Besides, they wanted a clubhouse that was solely theirs, where they could party and work on their bikes and do other serious things. They began looking around for some land, and it didn’t look like Williamsburg would work out any more.

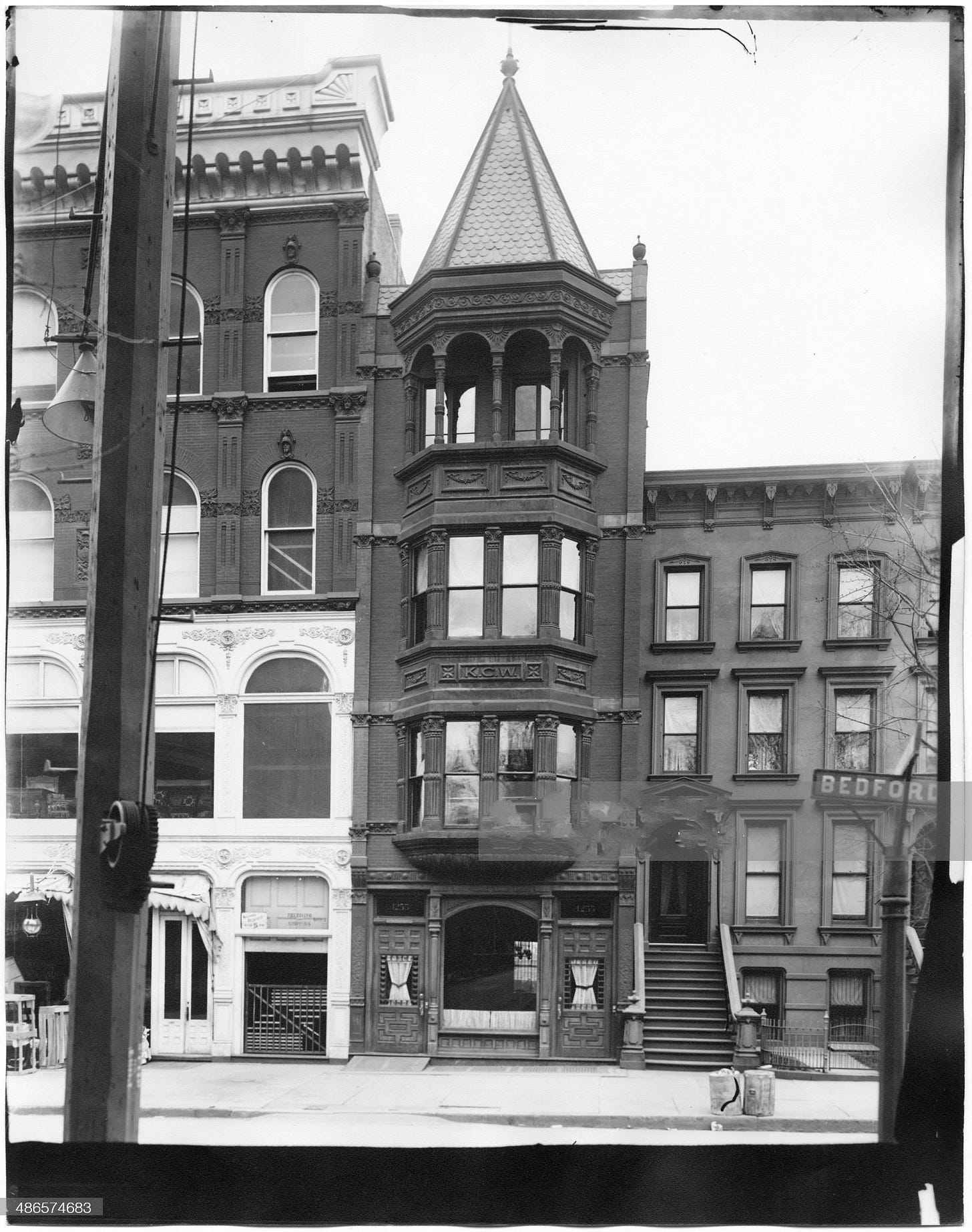

The most popular part of town was now Bedford, and Bedford Avenue. Brooklyn’s longest street was bicycle heaven and was very popular with all kinds of bikers. An ideal excursion would be to start in Williamsburg and bike all the way out to Sheepshead Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. The Wheelmen had done it hundreds of times. Bedford Avenue would be an ideal place for a clubhouse. Because the street was so popular with bikers, many of the best cycle shops were also along its route. They put some money down, and began building a clubhouse on Bedford, near Brevoort Place and Atlantic Avenue.

They started planning the building in 1887 and moved in the next year. The new club gave them room for billiard and card rooms, a dining area and kitchen, meeting rooms and a large space for a bike workshop, where members could make repairs and soup up their wheels. The clubhouse, a four-story row house, also had facilities for those rare occasions when they allowed wives and other females to come over for social events and programs. This building still stands, although it’s unrecognizable, and probably won’t be there much longer.

In 1892, the large storefront building next door to the clubhouse burned down. The Wheelmen’s headquarters was only slightly damaged, but it got them thinking it may be time to move again. They were still growing and had outgrown their new space already. They began looking around for another location to buy or build. One location that intrigued them was a large mansion at 78 Herkimer Street, between Bedford and Nostrand avenues. They bought it for $30K and began making plans.

In 1894, those plans fell through, as the house wasn’t big enough, and they sold the building to the Irving Club. A new location was found; right next door to the Union League Club, on Rogers Avenue, between Dean and Bergen streets. The building committee decided what they wanted in the club, and the building commenced. The new facility was quite elegant and looked more like a stodgy men’s club than the headquarters of a bike club. It had all the same amenities as their old space, and something new – a bar. Apparently most of the bicycle clubs in Brooklyn were adhering to temperance standards, but as the century was coming to a close, they wanted, and got, a bar. It was called a café, but they served and sold liquor.

By this time, the KCW were still the racing kings of Brooklyn, but many of their growing membership were more interested in the social aspect of the organization than extreme biking. In addition to the racing team and the trick riding team, they had those who just wanted to ride with an established group. There were many women who were interested in those activities, as well. And they also had other teams. They had a poker team, a billiards team and a very active bowling team. The club had several lanes in the basement. All the teams made the papers quite frequently, especially the bowling team, as bowling was the team sport de jour at the end of the century.

Riding in the parks, especially Prospect Park was a goal of most of Brooklyn’s recreational cyclists. They were lucky to have an eager ally and fellow biking enthusiast in charge of the parks. His name was Timothy L. Woodruff, and he was appointed Brooklyn Parks Commissioner in 1896. Woodruff was a wealthy businessman, political animal, and sporting enthusiast. He was a leader of the Republican Party in the State of New York and was elected Lieutenant Governor of the state three separate times under three different governors, including Teddy Roosevelt.

While Brooklyn Parks Commissioner, Woodruff was able to institute the first dedicated bike paths in Prospect Park, as well as trails leading from the park to Coney Island. He instituted bike lanes down Flatbush, Fort Hamilton and Ocean avenues. He lived in Park Slope, and was a dedicated city horseman, and so joined recreational riders’ concerns with those of bikers. He built rest stops for men and beasts, with drinking fountains and benches.

Woodruff was one of the men associated with the Good Road Association, a group of city officials and private citizens all advocating for the improvement and paving of all the city’s streets. The wheelmen were the biggest boosters for this group, and worked hard to persuade the city to pave the streets in a speedy and timely manner.

By the early 1900s, the club was still growing strong. The Union League Club had erected a large statue of General Grant across from both clubs, and Grant Square was one of the most fashionable parts of town. There were elegant restaurants, fine apartment buildings and homes, and a theater was coming, as well as a hotel. This was the perfect spot to be in. It was also the perfect time for the automobile to begin to take over Bedford Avenue.

Automobiles began appearing on Brooklyn Streets in the mid-1890s. Only the rich could afford them, but there were a growing number of wealthy people in the area. In only six or seven years, the automobile took off in the popular imagination, with dozens of car companies selling all kinds of vehicles. Dealerships, showrooms and service garages started to congregate on Atlantic and Bedford avenues. Bedford Ave had so many, it gained the nickname “Automobile Row.”

Like a child with a new toy, many well-to-do Brooklynites dropped their bicycles at their feet, forgot all about them and moved on to the car, beginning a love affair that hasn’t stopped since. Membership in the KCW began to drop off. They began embracing the automobile too, and offered garage space and sponsored auto events, but it wasn’t enough. By 1904 they couldn’t afford to keep their new clubhouse. It was less than ten years old. The club decided to officially disband.

They sold the building that same year to Professor Mac Levy, a popular physical culturist, who planned on turning the elegant building into his center for physical culture, aka a gym, complete with a Turkish bath, all upstairs. The ground floor was heavily renovated to turn it into an automobile showroom. After several years as an auto showroom for several different companies, a fire gutted the building. It was rebuilt and served once more as a place to sell cars.

At some point the building was torn down and by 1975, the empty lot belonged to the City of New York. In 1976, they sold it to the Washington Temple, a Pentacostal church which is headquartered in the old Loew’s Theater, across the street from this location. Today, the Temple uses it as a parking lot for church vehicles.

The Kings County Wheelmen are gone, but they weren’t forgotten. They had their first reunion in 1917 and got together from time to time until most of the members were dead. As the more prominent members died, the Brooklyn Eagle would bring up the club again, and marvel at their importance and accomplishments in the world of Brooklyn amateur sports. There would never be another club as famous as Brooklyn’s own Knights of the Silent Steed. Someone should start them up again. The bicycle has never been more popular.

@suzanne - May we organize an "author's night" for you at Paine Castle Troy? Similar to what we do for Cafe Yes (Don R) ?

Bill from Brooklyn, inveterate bicyclist there since 1970, historian and member of the old League of American Wheelmen, wanted to write this himself, but is glad he didn’t because Spellen of Troy did it so much better. Must be they saw it from a distance.