Miss Dillon’s Gas Company

This is the story of a woman you probably never heard of. She was a ground breaker, role model and inspiration for business women everywhere. She should be remembered.

Throughout much of the 19th century, aside from water, gas was THE utility, supplying light, heat and power. In Brooklyn, almost every neighborhood had its own gas company, with some neighborhoods served by competing carriers. Each had their own local gas plants, and their own lines which ran below the street and up into individual homes and businesses.

Each company wanted to control their neighborhood completely and solely, and most of these companies were looking to expand into other neighborhoods and take them over as well. The more ambitious companies did just that, and by the end of the 19th century, Brooklyn had gone from many gas companies down to only a handful. In 1895, seven of them consolidated to form Brooklyn Union Gas. They reigned in Brooklyn as the largest gas utility until 1998, when Brooklyn Union Gas (BUG) merged with the Long Island Lighting Company (LILCO) and became the Key Span Company, which was then purchased by National Grid.

BUG took over almost all of Brooklyn’s gas business, but there was one company that held out – a company that serviced far-off Coney Island. They were not competitive, they just wanted to service Coney Island, the nearby beach communities and Gravesend. It was called the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company, and it had its headquarters and gas plant on Neptune Avenue in Coney Island.

The company was founded by a group of entrepreneurs in 1877. They staked out the Gravesend section of Brooklyn as their own, and called their new utility the Kings County Gas Company. A Gravesend man became president, but the stockholders were mostly men from other parts of Brooklyn. Gravesend was growing, especially as Coney Island started to become a resort area for the rich, and the plant grew, was expanded, and grew some more.

The name of the company was changed to the Coney Island Gas and Fuel Company. When Brooklyn became part of Greater New York, in 1898, the company changed its name again, this time to the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company (BBG). As electricity began replacing gas for lighting, their market changed, but the company remained successful, transferring its attention to heating and appliances.

They petitioned to offer more common and preferred stock to raise money and chose a new board of directors. The company, although not as powerful or large as Brooklyn Union Gas, was doing well, and the price of its stock continued to rise.

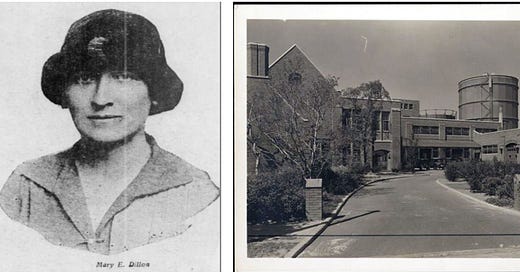

Far removed from the boardroom of a large utility, a young woman named Mary E. Dillon was growing up in Coney Island. She was one of twelve children and had to leave school at Erasmus Hall High School before graduation to work to help support her family. One of her older sisters was the only female worker at BBG, and when she left her job to get married, Mary applied and replaced her as the only female in the company. Mary was 17 and the year was 1903.

Mary knew nothing about the gas industry and started out in the office as the “office boy” as she would later call herself. Anything they asked her to do, she did, and over the next few years, she learned everything about the gas business, from billing to operations. She was like an early movie heroine, a pretty, petite and blonde young woman who made her way in a man’s world. More women were eventually hired in the company, but there were very few women like Mary Dillon.

Three years after being hired, Mary had gone from junior clerk to office manager, at the age of 20. By 1912, she knew the gas business inside and out, from top to bottom. She was so knowledgeable that she was selected by the general manager to be his assistant. Seven years later, her manager left his position. Mary Dillon was the obvious choice to succeed him. She knew more about Brooklyn Borough Gas than anyone else in the company. But she was a woman, by then a 33-year-old unmarried woman. It was unheard of that a woman could manage a gas company.

The company was running well. Their stock was on the rise, and was often touted in the papers as one of the better utilities to invest in. The board decided to split the difference. They did not hire another general manager, and allowed Mary to do the job, but without the title, or the salary. In 1924, the directors finally gave her the title of general manager and vice president of the company. A year later, the company was sold to a new owner, and Mary Dillon was voted in as a member of the board of directors.

Miss Dillon was now in the big office. She had gotten married in 1923 to Henry Farber, a businessman. The couple lived in Sea Gate, close to Mary’s office in Coney Island. She kept her maiden name, however, and throughout her business life always was known as Miss Mary E. Dillon. In March of 1926, Mary Estelle Dillon was voted in as President and Chairman of the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company. She was the first woman in the world to head a utility company. The company was worth five million dollars, and had 500 employees and served 170,000 customers. It was the 25th largest utility company in the country.

The news of a woman running BBG made the papers, and everyone wanted to interview the first woman to run a utility in the United States, no, the world. But not everyone was happy about it. One writer in the Brooklyn Eagle, columnist John MacElhinney, wrote “We note that the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company, a $5,000,000 company, now has a woman president. She must be a wonderful woman and it would be a privilege to meter.” He must have waited days to use that pun.

“She will probably state that the happiness of her success in the business world is as nothing compared to the happiness she had when working over her own stove in her own home. She will also, since she is a good business woman, advise other women to stick to housekeeping and to do a lot of cooking. This gas company’s secretary and treasurer are also women. However, it is reported that the janitor and the porters are men.”

The Brooklyn Eagle did send a female reporter out to Coney Island to interview Miss Dillon. That reporter, Marjorie Dorman, generally spent her days reporting society weddings, luncheons and other “women’s stories.” Her piece, situated in the women’s section of the paper, began, “And now it’s the bobbed haired president of a public utility who holds the center of the Brooklyn stage and blazes a national trail. She is pretty Mary Estelle Dillon who yesterday was elected President of the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company.”

The article went on to note that Miss Dillon was actually in real life, Mrs. Henry Ferber, but much of the article talked about what Mary Dillon looked like - her petite frame, pretty blonde hair, blue eyes and girlish figure. Her fashionable, but practical business clothing was also discussed. Finally, the article got down to business, and the reporter asked Miss Dillon about her rise to success. Mary Dillon was very candid. She spoke about her start in the company as “the office boy.”

“I wanted to know everything about the business there was to know. Women themselves are to blame for their lack of interest in the engineering problems of business. Women, for the most part, lack courage. Men take it for granted that women can’t understand the technical phases of business, and the women have a tendency meekly to acquiesce instead of asserting and insisting upon their right to be in every phase of business. I want my girls to feel they are capable of doing anything men can do. It is the only way for a business to progress.”

Mary knew that while the gas industry might be thought to be a messy man’s world, it was, in fact, used primarily by the women of Coney Island. Gas stoves and other appliances were taking over the market, and these were women’s tools.

The kitchen had gone from the exclusive domain of servants to the heart of the modern home. Whether one lived in a house or an apartment, every woman in Coney Island wanted a new and modern kitchen, with countertops, cabinets and the newest gas appliances. Appliance companies were opening everywhere, as stand-alone stores, or in conjunction with major department stores. What better place to show what an appliance can do than at the gas company?

Gas powered stoves and other appliances were the moneymakers for the company. Why not bring women into the gas company itself, by designing a headquarters and showroom where women could come in, examine and buy the latest gas-powered appliances, and learn new recipes and techniques in how to use them? She didn’t have to pitch this to anyone higher except the board of directors. They thought it was a great idea, and plans for a brand-new headquarters for Brooklyn Borough Gas were put into motion in 1929, and the facility was completed in 1931.

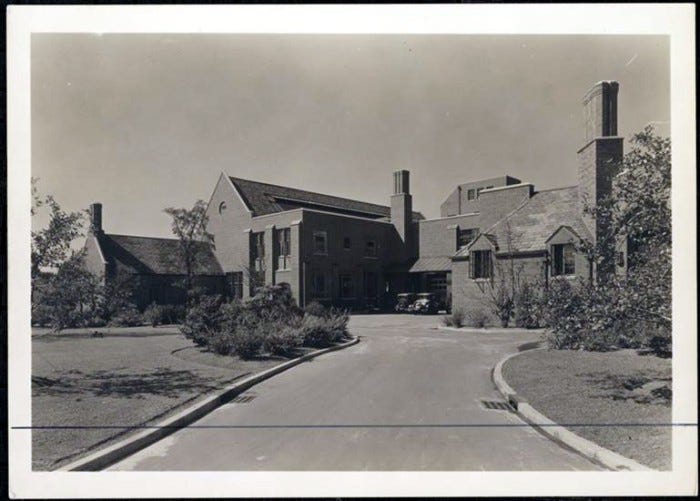

The new facility was built near the old, on Neptune Avenue at Shell Road. The architects and engineers of the project were the Manhattan firm of Block & Hesse. The new facility had a business office where customers could pay bills or speak to representatives. It had a laboratory for testing appliances, and a very spacious showroom where the newest appliances could be viewed and purchased. The “laboratory” was a huge test kitchen, where classes and demonstrations were given for not only stoves, but washers, dryers, fireplaces, heating stoves and other gas-fueled appliances. The company’s executive and business offices were here too.

In addition, the facility also had a garage for the utility and repair trucks, railroad and motorcar loading platforms, for shipping and receiving, equipment storage rooms, repair shops, tool and machine shops. Looming behind the facility were the gas storage tanks, and around that, the gas refinery itself. The new building was state of the art and was heated and cooled by a gas boiler furnace. The finished complex was one of the winners of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce’s Architectural Excellence Awards for 1931.

The new buildings were in a campus-like setting, and had it not been for the giant gas tanks, could be mistaken for a school. The grounds were beautifully landscaped, with trees, shrubs, flowers beds and lawns. The main building housing the offices and showroom was designed in a Jacobean, Old English style, with large windows and a large inviting entryway with herringbone brick sidewalks. There were plants everywhere, including inside the offices and showroom. The showroom was designed to appeal to a woman’s interior decorating sense and invoked a sense of home and comfort.

Although the Great Depression had a great impact on Brooklyn and the entire country, the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company stayed strong. Its stock was strong, and its new complex in Coney Island was a big hit with consumers. The Brooklyn papers had story after story about the programs that took place at the new facility. There were regular cooking classes that taught homemakers how to prepare good food for less money. They learned how to make nutritious meals with lesser cuts of meat and with new recipes to stretch vegetables and grains. They were also introduced to new appliances which could be purchased from them, or from their trade partners, local appliance and department stores.

Mary saw her company through the Great Depression, on into the World War II era. There were gas shortages as the oil used to refine gas was diverted to the military. BBG took part in the war effort. Dillon organized the Brooklyn Defense Recreation Committee. She called on the presidents and chairmen of many of Brooklyn’s largest stores and companies to join her on the board or contribute to the cause. The Committee ran two canteens for soldiers and sailors, one down by the Navy Yard. The Committee also had fund drives, collected scrap metal and took part in civil defense drills and other activities. When a new board was elected, Mary Dillon was asked to become its honorary chairwoman.

By the time the war ended, Mary Dillon had put in over forty years with Brooklyn Borough Gas. She had long since passed the days when men didn’t think she could run her company. In 1942, Mary was appointed to the NYC Board of Education. She was elected chairman two years later, and in 1945, she was unanimously elected the President of the Board, the first woman to be so elected.

A year later, she announced that she was retiring from the Gas Company in order to devote her attentions to the Board Of Education on a full-time basis. Not bad for a woman who had to leave Erasmus Hall High School in her senior year to go to work to support her family. She never graduated from high school, which never stopped her from achieving great heights.

In 1948, Mary’s husband, businessman Henry Farber died. The couple had no children. After retiring from the Board of Ed, Mary moved to Vermont. She lived there until 1973, when she packed up and moved to Hawaii. She died on October 20th, 1983 at the venerable age of 93. What a life she had.

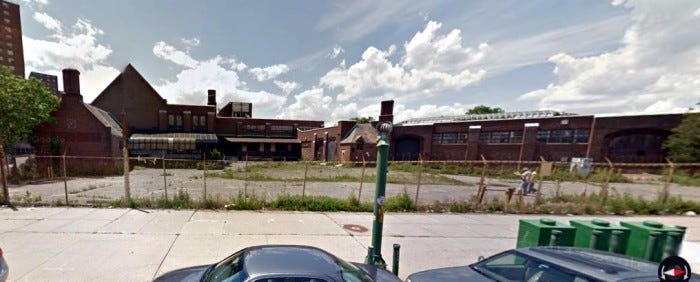

In 1959, Brooklyn Union Gas finally took over Brooklyn Borough Gas. When BUG became Key Span Energy, the facility changed signs once again. Gas had also changed. From its inception through Mary Dillon’s years at the company, gas was manufactured and refined at this plant through the burning and processing of coal. It was a messy business that took up a lot of room and equipment and was the reason the two huge gas storage tanks loomed over the facility. That was just the very visible part of the operation, there were outbuildings and tanks, coal storage, generators, tar storage tanks and separators and more.

It goes without saying that all of this also produced a lot of contaminants. In 1951, BUG switched from manufactured gas to natural gas. Between 1961 and 1966, the company began dismantling the manufacturing facility, which was demolished and plowed over. By then the only thing that remained of the 1930 facility was the campus of buildings that was the pride of the company. Key Span was now in charge of a huge, contaminated site.

They closed the campus and negotiated with the government as to how to clean it all up. They had to excavate the tar coal fields and dispose of all solid waste off site. The Coney Island Creek had to be dredged and tons of contaminated sediment was carted off. An ecological buffer zone had to be created to prevent more contaminants from leaking into the creek, or in the surrounding land. All this cost millions, and was undertaken in the early 2000’s.

The BBG Campus buildings sat vacant. The buildings were scheduled for demolition, but the entire campus was still eerily intact for years, a curiosity to those who passed and didn’t know its history. Many people assumed it always belonged to Brooklyn Union Gas, and only old-time locals remembered Brooklyn Borough Gas. The last pictures on Google Maps, captured in 2012, show the abandoned buildings. The complex was torn down in February of 2014. A large self-storage facility replaced it.

It was a good thing Mary Dillon did not live to see it.

What a great story! It's a pity the main building wasn't considered for landmark designation. It surely deserved it!

Great stuff! This one is really from "deep in the crates" as the DJs used to say - I love it!