Raising a Cup to King Coffee

Do you know what a strong impact coffee has had in our culture and our collective society? Even if you don't drink it, you'll find this interesting.

(I was going to post about the Blizzard of 1888, but who really wants to be reminded of the worst snowfall the East Coast has ever seen on a snowy day? Better to be somewhere warm and read about coffee.)

If coffee was a controlled substance, many of us would be addicts of the worst sort. Our national morning jones for caffeine has been the catalyst for fortune and failure over the centuries. Everyone loves a coffee shop, and most are welcomed into almost any neighborhood like a water fountain in the desert. There have been countless arguments and discussions regarding ranking the best coffees in the world, how to grow the beans, how to roast them, package them and brew them. Our stores are full of different devices that do whatever we need to get us our fixes.

Although many people, especially in upscale urban and suburban communities, swear by their special blends, their small batch, artisanal and exotic coffees, most of the coffee brewed in America comes from a few large companies that supply supermarkets and restaurants across the nation. The Arbuckle Brothers, working out of Brooklyn, were one the coffee giants of the 19th and early 20th century. They roasted and packaged the first popular coffee brand, called Ariosa, and created Yuban coffee, a brand that is still on the market after over 150 years. Here’s their story:

A Short History

Coffee is said to have originated in Ethiopia. Legend has it that a shepherd noticed his goats enjoyed eating the berries on a certain bush. Afterwards, they had boundless energy and wouldn’t sleep at night. The shepherd told this to a monk, who made a drink from the berries so that he could stay awake through his prayers, and coffee was born. It soon became a popular drink in the Muslim world.

Coffee came to Europe by way of North African and the Middle East way back in the Middle Ages. Its power as a stimulant caused it to be both praised and banned by several different cultures and religions. Venice, which traded heavily with North African Muslim nations, was the first European city to savor coffee. The Venetians opened the first coffee shops in 1645. They began the custom of adding milk and sugar to the brew. By the 1600s, coffee made its way to England, France and many other European countries. By 1675, there were over 3,000 coffee shops in England alone. But coffee was an upscale drink, enjoyed only by the privileged.

There are all kinds of tales about men smuggling coffee beans across borders, with the goods taped to their stomachs, as well as tales of people sneaking into royal orchards to steal cuttings. Coffee was not going to be the drink of royalty and the rich for long. There was too much money at stake. Different kinds of coffee can grow in different climates. European explorers took plants on their expeditions to new lands, and by the 1700s, coffee was introduced to Ceylon, India, the Caribbean, Central and South America, parts of Africa and anywhere else it would grow. Large plantations were established in most of these places, depending on Native, African, slave or indentured labor. Coffee came with a high price in human life and toil.

Here in America, coffee began coming into its own after the Boston Tea Party. Many patriotic people switched to coffee to support the cause of independence, and never went back. It soon became the American hot beverage of choice. The first coffee shop in New York opened on Pearl Street, in Lower Manhattan, in 1793. They roasted their own beans and sold to taverns and restaurants in the city, beginning the coffee obsession in New York.

The Coffee Business in Manhattan in the 19th Century

Manhattan soon became the green coffee warehouse of America. Beginning just after the end of the Revolutionary War, and on into the 19th century, New York became home to some of the largest coffee importers in the world.

The coffee beans came primarily from the Caribbean, Central and South America, with Brazil the largest exporter. But green coffee beans rot after a short time. The coffee importers realized that to preserve their precious commodity, they needed to either become coffee roasters themselves or send their coffee to independent roasters.

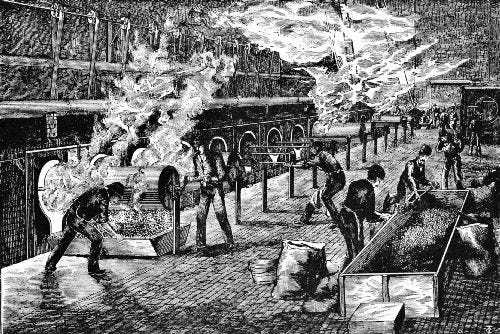

The business of roasting coffee beans practically took over the real estate of Lower Manhattan. Roasters were everywhere, including on Wall Street. The smell of roasting coffee must have gone a long way to dispersing many of the less savory smells of the wharves and streets. The coffee merchants were clustered in the warehouses around the South Street seaport. The roasters spread outward from there, clustered near their customers. Great fortunes were made by both groups.

By 1876, 75% of the coffee coming into the United States was coming into Manhattan and Brooklyn. In 1882, the Coffee Exchange was founded to trade this valuable commodity on Wall Street. Only 20 years later, in 1896, 86% of the country’s coffee supply landed in New York Harbor.

The Coffee Trade in Brooklyn

Brooklyn had a lot more space for storage than Manhattan did, with a much longer coastline dedicated to shipping. Manhattan was too crowded, so ships began preferring Brooklyn as their final destination. Beginning after the Civil War, the shoreline under Brooklyn Heights was built up into a solid wall of “stores,” – long warehouse buildings that housed everything from cotton to hides, to lemons, jute, tobacco, sugar, and of course, coffee.

The Empire Stores and the Tobacco Inspection Warehouse are the only surviving building from this era, a time when the massed warehouses were called “the walled city.” The Empire stores were built in 1869. These brick warehouses were large empty and dark spaces meant to store goods. The large openings made it easy to hoist goods into the stores, while the metal shutters kept the elements, fire and thieves out.

Coffee was being shipped to the Empire Stores and other warehouses from the Heights to Red Hook in record amounts. The green beans from all over the world made their way here. They came in large burlap bags that were stenciled with the country of origin, variety of bean, and grade. By the end of the 19th century, most of those beans were going into the roasters of the Arbuckle Brothers Company, the largest coffee roasters in Brooklyn, and one of the largest and most successful coffee companies in the world.

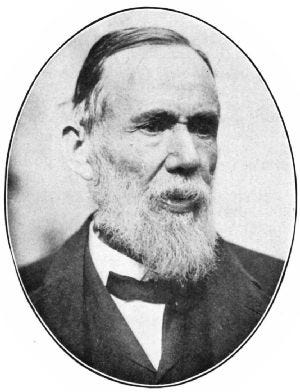

Brothers John and Charles Arbuckle came to Brooklyn from Pittsburgh. Younger brother John was the genius behind one of the most successful coffee companies in America.

The Arbuckle Family History

Perhaps it was the water, or more likely, just a combination of Scottish drive and determination and pure coincidence, but Allegheny, Pennsylvania produced several late 19th century industrial giants. Charles and his younger brother John Arbuckle were the children of a successful Allegheny woolen textile mill owner and his wife. John was born in 1839.

Allegheny was home to a large Scots population, most of whom were weavers and textile mill folk. This trade had brought the family of another Scot to Allegheny - that of a young boy named Andrew Carnegie. Young John Arbuckle was a classmate of another future industrial giant – Henry Phipps, later known as the “Coke King.” (That’s steel production, by the way.) The two boys sat next to each other in class. Andrew Carnegie was in the same school, in another classroom.

John also had an industrial and mechanical inclination but decided against local steel production. His inventions would take him in a different direction. Because his family had money, young Arbuckle went to college, unlike Andrew Carnegie, who had to support his family while still a child.

Meanwhile, in 1859, his brother Charles, along with his uncle Duncan McDonald and friend William Roseburg organized McDonald & Arbuckle, a wholesale grocery business located in Pittsburgh. In 1860, they bought John into the business, and a few years later, McDonald and Roseburg retired, leaving the new company, Arbuckle & Co. to the two young men. They were soon one of the largest and most successful grocery businesses in the city.

Arbuckle Coffee – the Early Days

One of the items the brothers dealt in was coffee. For many households, especially those outside of large cities, coffee was purchased as raw green beans, which were roasted on the stove by the homemaker. This process was rather wasteful, as well as time consuming. John thought it could be done better, by them, and their roasted coffee could be sold in small bags, ready for grinding and consumption.

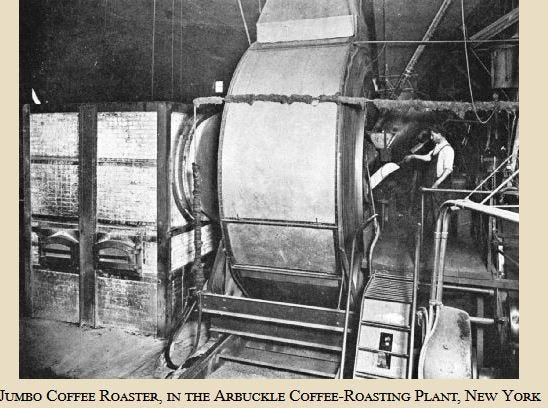

John had become obsessed with coffee. His inventive mind never stopped thinking of ways to improve the roasting process which was at the heart of a superior cup of coffee. His first patent, issued in 1868, was for a process of glazing the beans using a sugar and egg coating. This sealed the pores, trapping in the flavor and aroma, even before roasting. It took him another 35 years to perfect his roasting machinery. His huge roaster suspended the beans in superheated air, not allowing any of the beans to touch the surface of the heated iron containers during the process.

Even before his perfected process, by 1865, John had achieved the best roast possible for the day, and his beans were ground and packaged in small bags with original packaging and artwork. Believe it or not, his idea was met with skepticism by his brother, and derision by his competitors, who called his packaging in “little bags, like peanuts” a ridiculous idea.

Their signature brand “Ariosa” was packaged in small, one pound branded loafs of freshly ground coffee. This simple packaging was so successful, no one was laughing at him for long. The entire country was soon clamoring for compact packages of Ariosa coffee, the first national coffee brand, launched nationwide in 1873. Ariosa was called the “Cowboy’s Coffee,” as it was the brand of choice for cowhands on the range. The iconic cowboy campfires, with the coffeepot on the fire – later copied into movie and television legend? They were drinking Arbuckle Ariosa coffee.

Realizing that it was better for business to have an office in New York, where his coffee was coming from anyway, John moved north, while Charles kept the business going in Pittsburgh. The coffee business grew so much that Charles also had to move here, leaving the Pittsburgh office to employees. By the end of the 1870s, they had jettisoned all their other grocery business, and changed their name to Arbuckle Brothers – coffee dealers and roasters. In 1865, they had a single roaster. By 1881, they had 85 roasters in both Pittsburgh and New York. The business had not even begun to peak.

Arbuckle’s Brooklyn

John Arbuckle moved his operations from Manhattan to the Brooklyn waterfront, in what is now Dumbo. His coffee came into port and was stored at the Empire Stores, near Fulton Ferry. Arbuckle’s waterfront buildings enabled him to have the ships bearing his coffee from Brazil and elsewhere dock right outside his facilities. The coffee could be off-loaded, and quickly sent to his roasters, grinders and packagers in a rapid manner.

Henry Stiles would write in his History of Kings County that in 1883, Arbuckle had 500 hands, 48 roasting cylinders in operation each day, and 32 all night, each cylinder of copper, with 300 lbs. capacity, and taking 35 minutes to roast; 2,500 sacks of coffee, of 130 lbs. each are roasted, and 12 car-loads of ground goods shipped per day.

By the end of the 1890s, the Arbuckle Brothers owned a large complex of building in Dumbo, and had a railroad built to facilitate production and moving product. They were the largest coffee company in America.

The Sugar and Coffee War

Charles Arbuckle died in 1891. John brought his nephew, William Arbuckle Jamison on as a partner, as well as two trusted employees. The company was still growing and needed more and more sugar for its refining process. Arbuckle had been buying tons of sugar right down the road, from Williamsburg’s enormous Havemeyer Sugar Company, which processed Domino sugar. Because the companies were so close, barges or ships could simply make a short run around the harbor to make deliveries.

Arbuckle tried to cut a deal with Havemeyer, and get a discount, given the vast quantities they used. Henry O. Havemeyer wasn’t interested in dealing. He may have been threatened by Arbuckle’s domination of the industry. Not only did Arbuckle Brothers import more coffee from South America than anyone else, they owned the ships that carried the coffee. They owned the warehouses, the factories, and the railroad track through Dumbo to facilitate shipping materials and product more easily.

Arbuckle owned the patents for coffee roasting, as well as for the machines that roasted it. When another inventor patented a machine advancing the coffee business, Arbuckle purchased the patent, or went into a partnership with its owner. Arbuckle was also a master of advertising and packaging. His brand was everywhere, one of the first nationwide companies to do so. Every package of Ariosa came with redeemable coupons and had a stick of peppermint inside, just to sweeten the deal. Although there were other successful coffee manufacturers, both in New York and in other cities, Arbuckle was a force to be reckoned with - the King of Coffee.

Havemeyer was the King of Sugar, and he refused to cut a deal. So in 1896, John Arbuckle announced that he was going to open his own sugar refinery. He didn’t need the Havemeyers; he’d make his own sugar. In 1897, Arbuckle built a sugar refinery in Dumbo that could produce 3,000 barrels of sugar per day, much of which would be packaged in retail-sized two pound paper bags.

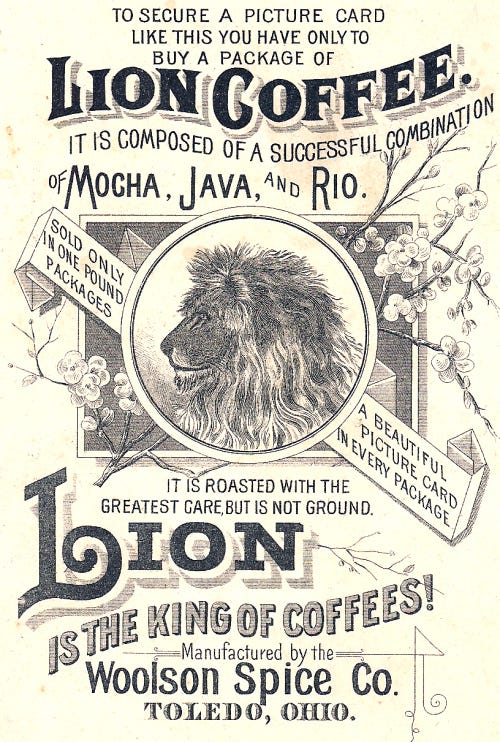

Havemeyer retaliated by buying the Woolson Spice Company of Toledo, Ohio, a major coffee roasting business. Their main product was a coffee marketed nationally under the “Lion” brand. This was the beginning of the Sugar and Coffee War. The “war” lasted several years. Arbuckle had the industrial facilities to refine his sugar and a sales organization already in place to market it. His refinery upped its production to 5,000 barrels a day.

Henry Havemeyer put himself on the board of Woolson and poured an unheard of amount of money into advertising to push Lion Coffee into the marketplace, touting its superiority over Ariosa. The battles went to the courts as well, with the lawyers on both sides getting rich. Both sides spent millions. The war between the two was so fierce and pervasive that the price of both coffee and sugar was depressed for much of the battle. Everyone in both industries suffered for it.

In the end, Havemeyer folded. He gave up the coffee business. Arbuckle continued to refine his sugar.

The Arbuckle Legacy

On a March day in 1912, John Arbuckle took to his bed, not feeling well. Four days later, on March 27th, he died at his Brooklyn home at 315 Clinton Avenue. The Arbuckle Brothers plant, and the Coffee and Sugar Exchange in Manhattan closed early the next day in tribute. His funeral was packed. John Arbuckle made his fortune in Brooklyn, but is buried with the rest of his family in Allegheny, PA. His beloved wife Mary died earlier in 1906. John Arbuckle left an estate of over 33 million dollars. A bequest in his will established the Arbuckle Memorial at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights, where he and his wife were members.

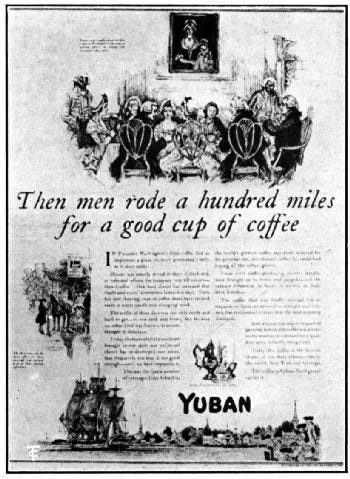

Arbuckle Brothers continued under the leadership of the nephew and his partners. The company’s growth continued. In 1913, they introduced a new coffee called the Yuletide Banquet. It was a premium coffee, a superior blend to their best-selling Ariosa and cost a bit more. It had been John Arbuckle’s personal blend, which he gave as gifts during the Christmas holidays. Yuletide Banquet was soon vying with Ariosa as the company’s signature blend. The name had been shortened to Yuban. Today, Yuban coffee is still on the market, still selling well.

At the company’s height, in the ‘teens, Arbuckle Brothers occupied a dozen city blocks along the waterfront in Dumbo. Their business was completely self-contained – they didn’t outsource anything. The buildings in the complex stored the beans. They were sorted, glazed, and roasted in their plants. The coffee was ground, packaged and shipped there. The sugar refinery did the same with the sugar. They had a stable full of horses and wagons for deliveries. That later changed to delivery trucks of all sizes. They even had a laundry that washed and dried the woven bags that the sugar and coffee arrived in, for re-use. Off-site, they established a barrel factory that made their own shipping barrels.

The factory had a hospital and a large, airy factory dining room for employees. Arbuckle had a large print shop where they printed all the labels and branded packaging and advertising. One of the company’s successful campaigns involved collecting value stamps that could be redeemed for goods. The stamps were printed on the coffee labels and were collected in books. All kinds of merchandise, from handkerchiefs to dishes, jewelry and other items were obtained. Arbuckle established a separate company to take care of the redemption, which grew to become a large enterprise in of itself.

From this, they established the Charles William Stores, a very successful mail order business. It did not have the Arbuckle name attached to it. The business was in Dumbo, as well, and took up several buildings in the Gair complex on Washington Street. The Arbuckle Brothers Company stayed in the family for at least two more generations. But by the 1930s, no doubt feeling the pinch of the Depression, the family began selling off their assets. The only brand they held onto was Yuban.

Today, Yuban Coffee is now a cheaper grade of supermarket coffee. A new Arbuckle Coffee, hand roasted in Arizona, and a 100% organically grown, free trade coffee, is now available. This new company has revived the Ariosa label and markets their coffee based on a combination of the Old West legend and the new artisanal coffee craze. They even enclose a stick of peppermint in their packaging, just as John Arbuckle did. Then, as now, it sweetens the deal.

(Much of the historical and industrial information and most of the historic images are from William H. Uker’s fascinating book “All About Coffee,” published in 1922. He was the editor of the “Tea and Coffee Trade Journal,” a trade publication, and was in the industry for most of his working life. He knew his coffee.)

"Realizing that it was better for business to have an office in New York, where his coffee was coming from anyway, John moved north,"

North from . . . Pittsburgh? I guess it is technically a tiny bit south, but much more west of NY than south of it.

Cuppa coffee, please. (As a born Brooklynite woulda said in those days!)

I was struck by the reference to Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights and that John Arbuckle established an Arbuckle Memorial there upon me of his death in 1912. It's said he and his wife were members there. For sure, it's the mid-late 1800s militant abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher who stands out among Plymouth's preachers. But it seems that Newell Dwight Hillis would have overlapped as pastor/preacher during Arbuckle's time. Wiki describes Newell as a "supporter of eugenics" who organized national "Race Betterment" conferences. I wonder, this being true, how it was reflected in the membership.