Redlining – How the Lines on a Map Determined Today's Urban Neighborhoods

An important part of the study of cities and of inequality.

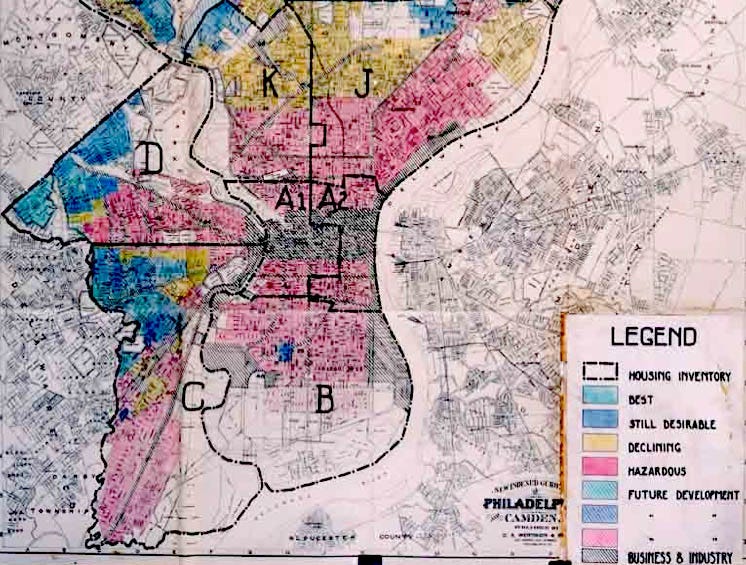

(HOLC map of Philadephia, showing the classification of neighborhoods, 1936-38) via Wikipedia)

You may have heard the term “redlining” in discussions of neighborhoods such as Bedford Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, or North Central in Troy. You may have heard that many parts of both cities were once redlined, but that unfair practice died out with mood rings and fringed jackets. Or did it? The power of a red line on a map is often stronger than we know.

The nation was in the grip of the Great Depression when the Federal Housing Administration was established in 1934. It was created to jumpstart the housing industry by making federally-insured, long-term, low interest loans available to potential home buyers through their local banks and lending institutions.

The FHA worked with the insurance and banking industries to come up with guidelines to ensure that their investment would not go to waste. They created HOLC, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, which became a governmental agency.

In 1935, HOLC was asked to prepare “residential security maps” for 239 American cities. The maps would show which neighborhoods were deemed to be the most desirable for investment and would give lenders their best ROI. The neighborhoods were ranked by the color of their respective zones.

Neighborhoods lined in green were the best. In many cities, these Zone “A” areas were new neighborhoods, with new construction, usually suburban. If more urban, they were the affluent neighborhoods where a bank’s money was guaranteed.

Blue Zones, the “B” areas, were excellent as well, only slightly behind green. They were listed as “Still desirable.”

Yellow, or “C” zones were in transition. They were usually the older parts of cities that were headed downhill, according to the descriptions. Incomes were falling, the housing stock was getting run down, and further decline was in the air. They generally had high immigrant populations. The guide to these maps classified the yellow neighborhoods as “Definitely declining.”

These neighborhoods were always adjacent to the worst designation – the “D” zones.

These neighborhoods were the least desirable. They were usually in the city center, were older districts, and were minority and immigrant neighborhoods. These neighborhoods were boldly colored in red, the color of “danger.” Redlined neighborhoods almost always had black people living in them. For cities without large black populations, they were always neighborhoods with a large percentage of the foreign-born. They were officially classified as “Hazardous.”

Banks lent to the top two tiers, offering lower rates, and more funds. The yellow neighborhoods got very little money, as they were seen to be headed towards red at any time. Only the best connected of lenders could hope to borrow here, and at a higher rate of interest. That would generally not include individual homeowners, either. The red zones were simply written off as if they didn’t exist or count. Banks made no loans to anyone seeking a mortgage within the red borders; no matter how qualified the borrower happened to be. This was “redlining.”

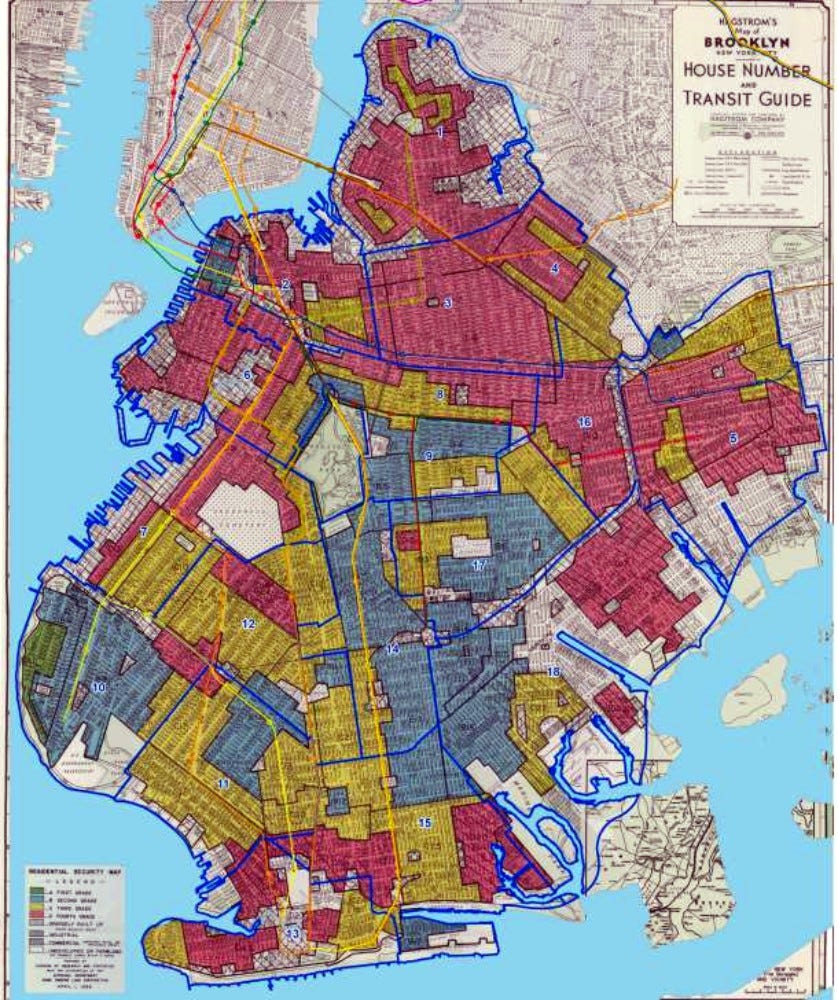

(HOLC map of Brooklyn, NY, showing the classification of neighborhoods, 1937-38) via Mapping Inequality, University of Richmond)

Brooklyn’s Redlining Map – 1938

We can see how the zones shake out in the 1938 map of Brooklyn prepared for HOLC. Only two neighborhoods make the green “A” listing – parts of Brooklyn Heights and the Shore Road area of Bay Ridge.

Many more make the secondary Blue zones, including most of Victorian Flatbush and Midwood, Flatlands, Park Slope’s Gold Coast and prime blocks above 7th Avenue, Bay Ridge and Dyker Heights, and the Prospect Lefferts Garden area, on up around the mansions of President Street and Eastern Parkway.

But more than half of the rest of Brooklyn was deemed declining or unacceptable. Yellow zone neighborhoods include the rest of Park Slope and Prospect Heights, parts of Clinton Hill, most of Bensonhurst, Borough Park, Cypress Hills, Sea Gate and Marine Park, plus more.

Red zones – well, they were everywhere, and included the neighborhoods of Bedford Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, Ocean Hill, Brownsville, Bushwick, Williamsburg, Greenpoint, East New York, Canarsie, Sunset Park, Gowanus, Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens, Fort Greene, Red Hook, Coney Island and the Sheepshead Bay/Gerritsen Beach area.

Yes, according to the real estate and banking boards who determined where the FHA money went, half of Brooklyn was totally unacceptable or on its way there - half of Brooklyn, including almost all of Brownstone Brooklyn.

Each zone had a file, with designations to be filled out by those categorizing the zones. The redlined D-zone files are shocking to the modern reader. They are racist, anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant and more. This is the neighborhood called D10, which includes much of today’s Brownsville, which at the time was primarily lower income, working-class Jewish, with a growing black population

Terrain: Flat

Favorable Influences: All city facilities (that would be public transportation, sewer and other infrastructure.)

Detrimental Influences: Congestion. Poor upkeep. Lack of pride. Pushcart vendors and curb markets. Elevated structures Fulton Street and Atlantic Avenue. Railroad and industry to east and south. Mixture of races. Communistic type of people, who agitated “rent strikes” some time ago.

Inhabitants – Occupation: Merchants, laborers, peddlers. Foreign-born families: 60% Jews and Italians. Negroes: Yes. Infiltration of: Jews , Negroes. Relief families: Many.

Security grade: D

This section of Park Slope received a “B” rating. That was good. Here’s why:

Terrain: Slight downward slope towards the west

Favorable Influences: Prospect Park, Adequate zoning and restrictions. New subway under Prospect Park West

Detrimental Influences: Traffic on the avenues

Inhabitants – Business executives and professionals. Foreign-born families: 15%, Irish and British, predominantly. Negro: No. Infiltration of: Jewish. Relief families: very few.

Security grade: B

Clinton Hill was a redlined D zone. It’s detrimental influences, which gave it a D rating were “Obsolescence and poor maintenance. Infiltration of Negroes. Elevated structures at Lexington Avenue, Fulton Street and Grand Avenue (elevated subway lines). Mixed races.” The population was categorized as: “Occupations: Poor laboring class. Foreign born families: 40%, Italian, Irish. Negroes: Yes, 50%. Infiltration: Negroes. (steady.) Classification: D.”

The Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood read like the Clinton Hill report. The neighborhood at the time was listed as Jewish-Irish, with a steady infiltration of Negroes. A clarification at the bottom of the report states, “Colored infiltration a definitely adverse influence on neighborhood desirability although Negroes will buy properties at fair prices and usually rent rooms.” Ah, there was money to be made here, from African American homebuyers! But not mortgage money to those homeowners.

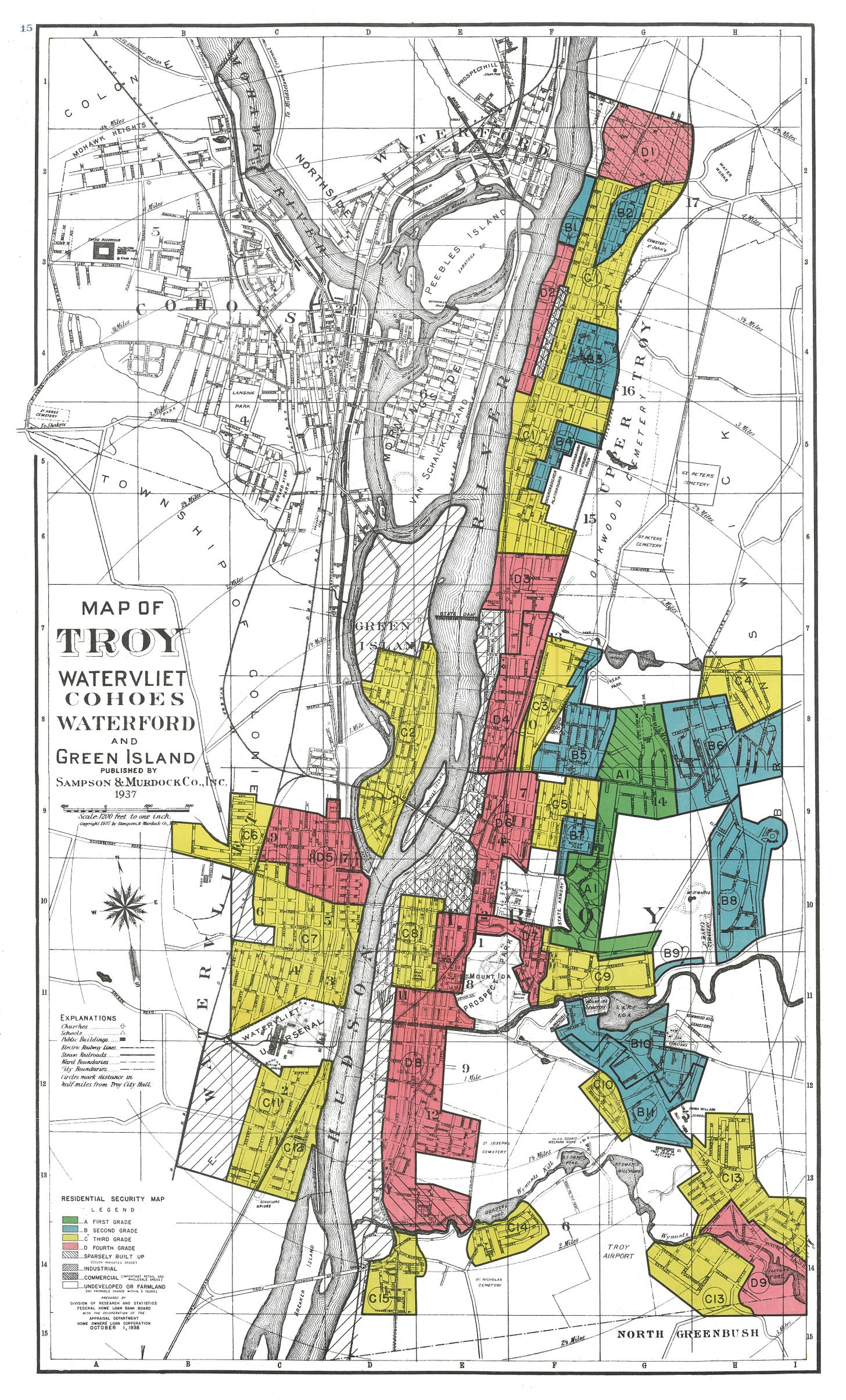

(HOLC map of Troy, NY, showing the classification of neighborhoods, 1937-38) via Mapping Inequality, University of Richmond)

The Situation in Troy, NY

Troy’s redlining maps are similar to Brooklyn’s, on a smaller scale. Troy was a thriving industrial city with heavy industry primarily on the southern end of the city, with garment factories and other industries lining the Hudson River front going north, and pockets of industry here and there throughout the downtown and greater city. But by the Great Depression, Troy was experiencing a loss of industry and jobs, leading to the deterioration of its working-class and poorer neighborhoods. The HOLC maps reflect this downward trend in much the same way as in Brooklyn. But for Troy, with a much smaller African American population, the “infiltration of Negroes,” while present, was not as devastating to the record as the neighborhoods of white immigrant families, the backbone of Troy’s workforce in previous years.

In 1938, the only neighborhood classified as “A” with a green designation was the area called “Parkway Village,” which was classified as “a newer development comprising the city’s best residential section for those of moderate means. Homes are modern, of modest size, and of attractive design. Plots are sufficiently large so as to prevent overcrowding. There is ample room for further expansion. The only vacant dwellings are those remaining unsold.”

Today, this is the area around Samaritan Hospital, around Beman Park, but not 15th Street, and across Hoosick to the border of Frear Park. It is primarily 1920s bungalows and Dutch and Colonial Revival single family homes.

Moving up the hill and into the Eastside neighborhoods, around Mount Ida Cemetery and up by Emma Willard School, those neighborhoods were ranked as “B,” for blue. They missed being green only because the housing stock was older. But they were desirable neighborhoods for this study and for lenders.

There were also blue neighborhoods in parts of Lansingburgh, around the high school and Knickerboker Playground and pockets here and there in Northern Lansingburgh. But the rest of the city was classified as “definitely declining” or “hazardous,” the yellow and red designations.

The classification of the area around Washington Park, today one of Troy’s most fashionable and desirable neighborhoods reads, “Detrimental influences: Age and obsolescence of structures. Trend of desirability: Slowly downward. Inhabitants: Occupation: shopkeepers. Foreign-born families: 60% Italians. Negroes: Yes, 5%. Infiltration of: Italians. Relief families: Quite a few. Clarifying remarks: This is an old section containing what were fine, old homes and mansions but which have long since lost their usefulness. A number have been converted for boarding houses or business purposes. Better class are found along Second Street and around Washington Park but the value of even these is questionable.” This part of Troy was deemed “Yellow – failing and definitely declining.”

All of South Troy was redlined and deemed a “slum area.” It was expected to sink even further in the next decades. The occupation of its residents were “Factory hands and laborers” The foreign-born were 25% Polish. Negroes: No. Infiltration: None. Relief families: Many. The neighborhood was described as “An old section of the city which has always been given over to the lower working class. Houses are built closely together and are typical of a ‘slum’ area.”

Downtown was not seen as residential enough to be classified. But today’s North Central was redlined as well, not surprisingly. This area included land from Hoosick Street north to Glen. The description reads: “Favorable influences: None. Detrimental influences: Age and obsolescence of structures as well as character of neighborhood and occupants. Occupations: Laborers. Foreign born families: 40% Italians. Negroes: No. Infiltration: Italians. Relief families: Many. Clarifying remarks: This is a very old and congested section which is entirely given over to the laboring class and in which there are scattered industrial plants. Prices are nominal and subject to offers.”

So, What Did This Really Mean?

The HOLC model was based on a life-cycle assessment of neighborhood change. The theory was that neighborhoods inexorably declined as housing stock decayed and architectural styles went out of fashion. This lowered values to the point that a “lower grade population” began to “infiltrate” the neighborhood.

Working class or foreign-born whites compromised a neighborhood’s integrity and accelerated the decline of housing values and neighborhood desirability, according to the HOLC model, making for a “C” listing, but far worse was the presence of black people, which precipitated the final demise of the neighborhood.

Almost all of the neighborhoods redlined in Brooklyn had large black populations. If they didn’t, like in Sheepshead Bay, they had large immigrant and lower working-class populations. They also contained much of the city’s oldest housing stock.

The threat of the “contagion” of black people was so omnipresent in their criteria that many neighborhoods, like Williamsburg, may not have had large black populations themselves, but they were next to black neighborhoods. The HOLC guidelines warned of black people passing through these neighborhoods, and eventually moving in.

Armed with the redlined maps, the city’s banks, mortgage and insurance companies could now justify their lending and policy practices. They closed their doors to redlined neighborhoods and lent very sparingly to those in the yellow lined areas.

Municipalities and businesses pulled their resources and investment out of redlined neighborhoods too, allowing infrastructure and services to fall apart. City governments acted as if these neighborhoods did not exist, and of course, the results were catastrophic.

In Brooklyn, it created the massive black neighborhood known through much of the 20th century as Bedford Stuyvesant, classified as a “ghetto,” which stretched from Williamsburg to Flatbush, Downtown to Bushwick, every block redlined.

Those in Redlined Neighborhoods Survive

For the people who lived in Bed Stuy and other redlined neighborhoods, the sale of real estate went on. If large real estate firms and banks didn’t want to deal with the neighborhood, then a separate system of brokers, financial institutions and brokers would carve out their own niches.

African American real estate firms were established which only sold within the community. They advertised in the neighborhoods, through word of mouth, and in black newspapers like the Amsterdam News.

Local black churches such as Concord Baptist Church and others began home buying clubs, allowing members to pool money to make down payments. The few black banks, savings and loans and credit unions offered mortgages and savings clubs as well.

Private lenders, many quite greedy and unscrupulous advertised in the communities, offering mortgages, but with huge interest rates and penalties. They were the communities’ first predatory lenders.

Despite the large interest rates, they were often the only game in town. Black home buyers worked two and three jobs to make the payments. They subdivided the row houses into apartments and rooming houses, families often taking up very little personal space to get higher monthly income.

The Fate of Redlining

Redlining continued through the 1960s and 70s. The new homeowners in Park Slope, Brooklyn and Washington Park, Troy during the great old house revival of the late 1970s and 1980s found many areas still redlined. But as more people began moving back into the urban core, banks realized that this was a fresh new market – these were often upscale people with money.

Redlining didn’t go out with a bang, but with the soft swoop of a bankcard in a terminal. All of a sudden the city’s major banks wanted to open neighborhood branches and lend to the communities. They began sponsoring rehab programs in conjunction with the utility companies and neighborhood organizations were established and encouraged.

Redlining still didn’t let go of communities like Bed Stuy, however. As property values increased, the predatory lenders came out in full force, offering easy terms to people they knew were not financially stable enough to be owners. Others preyed on elderly homeowners, offering loans to repair aging properties, knowing that many of their clients did not understand the terms or conditions of their loans. Foreclosure and predatory lender maps began to look like the old HOLC maps. Redlining’s legacy is still being felt.

We shouldn’t forget that a national agency in the United States of America in 1938 had a separate category for the foreign-born in a neighborhood. That Jews, Italians, Irish, Poles and others were not desirable, and brought a neighborhood down. Black people were so undesirable that we got our own category, singling us out in particular. The increasing numbers of all these groups into a city were considered an “infestation,” like rats or roaches.

We may have changed a great deal in the last 90 years, but it remains important that we remember HOLC and redlining. They were the definers of the “American Dream,” a dream that was not given to all equally, and is a part of American history.

Today, many of our older city neighborhoods across the country are hailed as desirable urban homes in walkable cities and downtowns. Everyone wants to live in these neighborhoods, and the ever-rising prices in city real estate is astonishing. Prices jumped up so fast, and neighborhoods once shunned by HOLC are now the hottest real estate in town.

In our rush to repopulate, we should never forget those who struggled to buy in the years of redlining, paying far more in interest than home buyers only blocks away, and that’s if they could get a mortgage. We shouldn’t forget their determination to own property, still considered the surest way to incur generational wealth. Those people preserved our neighborhoods, even in poverty. Their legacy is our neighbors and neighborhoods, ever striving forward.

Beautifully written....as always! I'll post on the "Designing History" LinkedIn page; please follow us too!

There has been some interesting clarification recently regarding the HOLC maps~

Redlining Didn’t Happen Quite the Way We Thought It Did, by Jake Blumgart, Governing Magazine, September 21, 2021.

https://www.governing.com/context/redlining-didnt-happen-quite-the-way-we-thought-it-did

"In recent years a once obscure lending practice has become a touchstone for America’s understanding of its racist past and the reverberations it still has today. But new research complicates our understanding of the historic practice of redlining, where certain neighborhoods are cut off from lending for reasons of race and class. It did not quite work in the way that it is popularly understood.

In mainstream journalism, and political discourse, redlining is associated with the maps drawn up by the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC). This New Deal-era institution was created to refinance extant loans for borrowers who were struggling during the Great Depression. In the late 1930s, the agency drew up color-coded maps that evaluated neighborhoods based on their presumed prospects, with those believed to have the worst outlooks drawn in red.

It has long been assumed that these maps, which covered most Black residents of American cities and roughly half of whites, guided lending and investment away from red areas and toward green and blue ones (which were almost all majority white).

But new research shows that the maps very probably did not guide private lenders or the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which clearly engaged in racist lending practices all on their own. The HOLC, however, actually loaned widely in Black neighborhoods and other red-shaded areas.

“If you're trying to use the HOLC maps to tell us how federal policy influenced things, then that's the wrong set of maps,” says Price Fishback, professor of economics at the University of Arizona. “Some people have been doing these long-range studies and saying this was all FHA policy using the HOLC maps. They've been using various techniques that require you to explicitly look at these boundaries. But they're using the wrong boundaries.”

Although the two agencies were set up at a similar time, HOLC was a temporary program (it ceased operating by 1951) meant to help homeowners who were in danger through no fault of their own. The FHA didn’t interact with existing loans, but was tasked to build a new insurance program backing “economically sound” loans with lower interest rates and longer duration periods than was traditional at that time.

Fishback and his co-authors are not arguing that racist mortgage practices did not occur. But they are trying to disentangle the policy of the two New Deal-era mortgage institutions, one of which engaged in heavily anti-Black practices (the FHA) and the other of which did not (HOLC). This also means that the famous redlining maps issued by the latter agency do not reflect how discriminatory lending was put into practice."