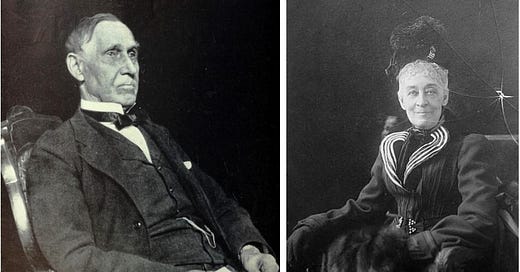

(Russell and Olivia Slocum Sage via Wikipedia)

I was recently asked to prepare and present a virtual lecture on Russell and Olivia Sage. During that research, which was a much deeper dive than when I researched this original piece, I discovered that “Uncle Russell” was not as bad as his reputation would suggest. In fact, much of what I wrote in this piece is wrong. So I’m going to make some changes and present a much more factual biography of the man, with source documentation. Stay tuned. (9/1/24)

The name Russell Sage is an important one in Troy, in New York City and around the country. We have the Russell Sage College(s), the Russell Sage Foundation, the Russell Sage Wildlife Management Area (Louisiana), The Russell Sage Junior High School and Russell Sage Playground in Queens, where also stands the Russell Sage Memorial Church. There is the Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences and the World War II era Liberty ship, the SS Russell Sage.

All this and more would lead anyone to believe that Russell Sage was a generous, civic minded hero, one of the greatest philanthropists this country has known, a man who dedicated his fortune to the betterment of society, the environment and the education of women and children. What a guy! What a mensch!

Except he wasn’t that guy. Not in the least.

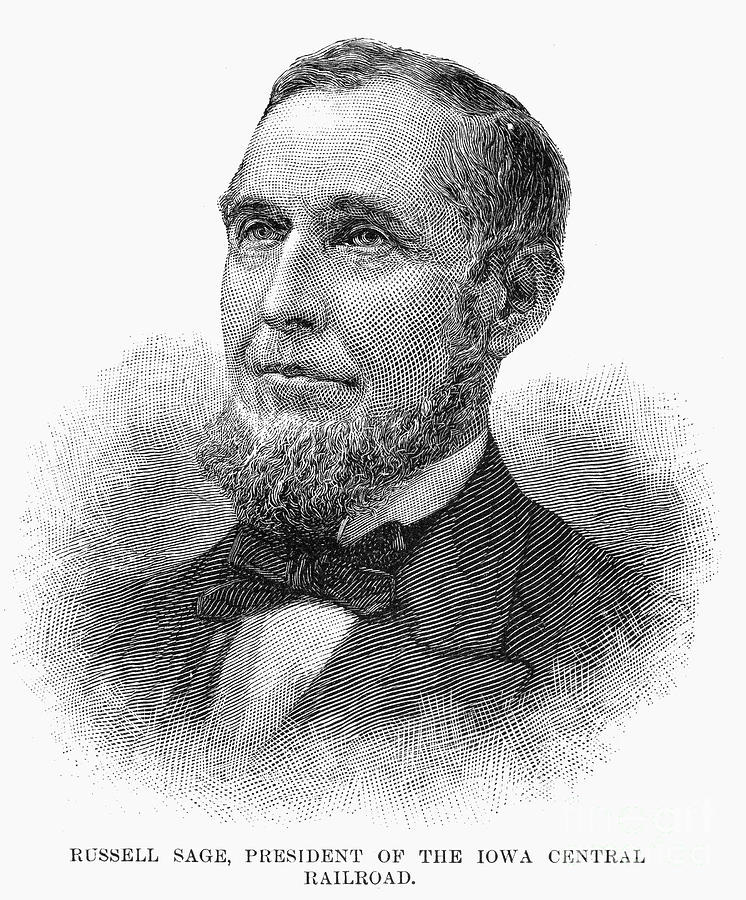

The real Russell Sage was a horrible human being, a man who never did anything for anyone, unless it benefitted him in some way. He cheated on his wives, was ruthless in business, and only donated to charity when it was a very public affair that made him look good. After his death it was hard to find anyone who had a kind word to say about him. History seems to pop people like him out every once in a while.

So why are all these institutions and charitable efforts named after him? Well, that’s the tale.

Russell Sage was not to the manor born by any means. He was the son of farmers, born in Oneida County, NY in 1816. He was from old New England stock, one of his ancestors is on record as a resident in Connecticut as far back as 1652. In the early years of the 19th century, his father, Elisha, his wife Prudence and their five children set out from Connecticut by ox train, headed for the Michigan frontier. But upon reaching Oneida County, in the Utica area, they found the land to be good and settled there, where Russell was born.

He attended local public schools until the age of twelve. In 1828, he left the farm to work as an errand boy at his brother Henry’s grocery store in Troy, NY. According to biographers, he also went to night school, where he paid a third of his monthly salary of four dollars to learn arithmetic and bookkeeping. He was also a voracious reader of markets strategies and newspapers. As a teenager he began financial trading on his own accounts, so that by the time he turned 21, he was able to buy his brother out. He ran the store for about a year, and then sold it for a tidy profit.

Troy was a crossroads city on the Hudson River with many a comfortable income to be made from the merchant trade. The new Erie Canal was bringing goods and people from the Great Lakes to New York City and Troy was close enough to Canada and the New England states to take advantage of goods traded north and east. Much of Troy’s central waterfront faced warehouses and factories, all with goods to sell.

Sage took his capital and with a partner started a wholesale grocery business in Troy. Because they had their own boats plying the Hudson, they could trade not only groceries, but also grain, horses from Canada and Vermont, and meat products, both fresh and cured. Sage was doing quite well.

In 1840 he married Marie-Henrie Winne, the daughter of a prominent Troy family. Eight years later, they moved into a large Gothic Revival house at 2nd and Washington streets, on the corner of the private Washington Park, which at the time was Troy’s most exclusive neighborhood. They lived there between 1848 and 1863. While in Troy, Sage was elected as a City Alderman from 1841 to 1847, while also serving as the Treasurer of Rensselaer County. From there, he was elected to two terms in the House of Representatives as a member of the Whig Party between 1853 and 1856, serving on the Ways and Means Committee.

(Russell Sage home, 177-79 2nd Street, Troy. The house was long ago cut up into apartments.)

After his terms in Congress, he retuned to Troy and his grocery business, but was now giving most of his attention to the stock market and financing ventures. He needed to be where the stock exchange and the power players were, so in 1863 he and Marie moved to New York City. One day by chance he ran into Jay Gould at a railway station. Gould was the manager of the Rensselaer and Saratoga Railroad, among many others. That encounter would change the direction of his business life. The two men hit it off and became friends and sometimes partners.

Jay Gould was already known on Wall Street as a canny railroad stock investor and a cutthroat competitor. What the highways of the late 20th century were to commerce and travel, the railroads were the same in the latter half of the 19th century. Great fortunes could be made through railroads, and as the years progressed, by the 1880s, Gould was well known as one of the most powerful of the class of ruthless railroad businessmen that gave rise to the name “Robber Barons.”

Russell Sage had the same killer instincts. He made his first big money selling puts, calls and privileges on Wall Street. A call option allows the holder the right to buy a stock. Conversely, the put option allows them to right to sell a stock. A privileged dealer is a registered broker or firm that deals in these options. In 1869 he was accused of being the leader of a usury group, overcharging borrowers with high interest loans. Basically, he was a loan shark. He was found guilty and fined but received a suspended sentence. He continued to work the markets.

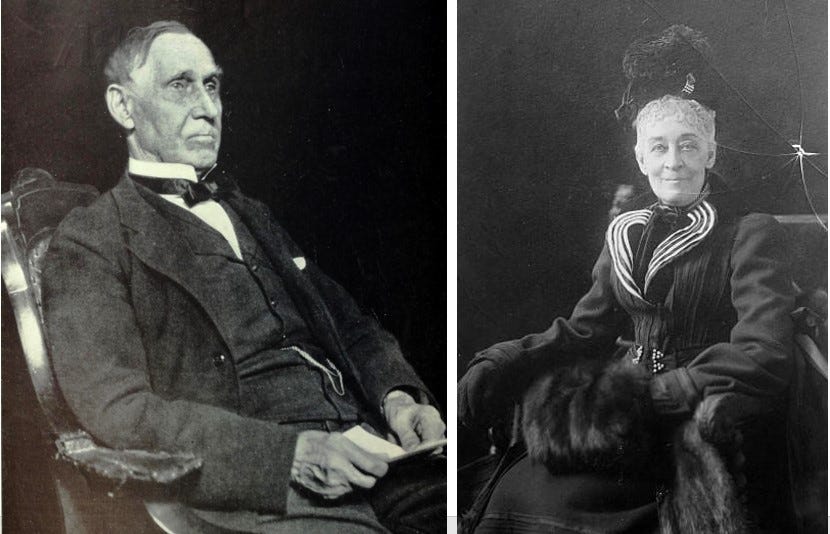

Sage bought a seat on the Stock Exchange in 1874. He invested in smaller western railroads, and was vice-president and president of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway for twelve years. Most of the nation’s smaller railroads ended up merging with larger lines, which then merged again to become very large and vital companies. Each time there was a merger, major stockholders like Sage became wealthier and wealthier.

He and Gould partnered in the management of the Wabash Railway, the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railway, as well as several other lines. He was the director of the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway. He also invested in and was a director of the American Cable Company and Western Union Telegraph Company. His most important position, which cemented his large fortune, was as a director of the Union Pacific Railroad, most famous for being a part of the first transcontinental railway. He was also an advocate for the building of an elevated transit system in NYC, another strong-arm deal with Jay Gould, and sat on the boards of several banks.

(The Sage 5th Avenue mansion, long gone. Photo: Daytonian in Manhattan)

Long story short – Russell Sage was now one of the Robber Barons and became very rich during what we now call the Gilded Age of the late 19th century. He was known as a man guided solely by profit, with few moral scruples, never yielding, and never giving anything to anyone. He would argue with a street vendor over the price of an apple. He moved to a brownstone mansion on Fifth Avenue, NYC’s latest exclusive street of the very rich. His home is long gone now, one of many such houses torn down for Rockefeller Center.

Along with his fierce financial pursuits came appetites of another source. It was well known that he had numerous affairs while married to his first wife Marie, who died of stomach cancer on May 7, 1867. They had no children. She’s buried in Troy’s Oakwood Cemetery, memorialized with a tall obelisk on the hill upon which lies the Sage plot. Marie’s family had been one of the founders of the cemetery. After a suitable time of mourning, Russell Sage found himself in need of a new wife.

Margaret Olivia Slocum also came from an old American family. Her father Joseph’s family immigrated from England to Massachusetts in 1630. She was born in Syracuse on September 8, 1828. Joseph Slocum was a successful merchant who did well when Syracuse prospered along with the Erie Canal. But he lost much of his money in the financial panic of 1837. The growth of the railroads, which drew business away from the canal, contributed greatly to the lowering of the family’s financial status.

In spite of their financial worries, Olivia was educated in private schools and was able to borrow money from a relative to attend Emma Willard’s Troy Female Seminary. The school was groundbreaking because of educator Emma Willard’s insistence that young women receive the same education as men; learning classical languages, mathematics and science at a time when many believed that such education was impossible for a woman’s delicate brain to process. Olivia thrived there, was mentored by Emma Willard and became a lifelong champion of the school.

She returned to Syracuse as a teacher, one of the few respectable professions for a single woman, and lived with her parents for over 20 years. The family continued to struggle financially, and in 1857, Slocum was forced to sell the house. The family had to live with relatives and friends. When the Civil War broke out, Olivia moved to Philadelphia, where she worked as a governess and volunteered in a military hospital. Her father died of tuberculosis in 1863.

(Young Margaret Olivia Slocum)

At some point before her father’s death, she was introduced to Russell Sage. Olivia was 41, an old maid in society’s eyes, brainy, self-reliant and not conventionally pretty. In her youth she had turned down several suitors, she had too much to do. But rumor had it that Sage had swindled money from Joseph Slocum when Slocum was desperately seeking funding. It was said that Sage later told Slocum that he would marry Olivia, and that would square them for the money that he owed him. Somehow, I don’t see Olivia agreeing to this arrangement, but times were different then, and women didn’t have a lot of choices.

Although Sage was a filthy rich widower, living in a 5th Avenue mansion, with a summer home on Long Island, NY’s society crowd did not particularly like him. His business dealings were ruthless, his morals lax and his affairs were well known and looked down upon. It wasn’t that many wealthy men were not also just as profligate, but they kept their liaisons quiet, and their wives pretended they didn’t know about them. It was all very civilized, but Sage didn’t care what people thought, and did what he pleased.

However, he was aware that he had been excluded from certain parts of polite society that he needed to be in, and a respectable wife from a good family would be his entry to that world. Margaret Olivia Slocum and Russell Sage married on November 24, 1869. It is said that after they said their vows, Sage turned around and left her standing at the altar, saying he had to get back to the office. Theirs would be a loveless, unconsummated and therefore childless marriage. Sage continued his dalliances and his life as if nothing had happened.

As the wife of a wealthy man, Olivia was expected to join New York’s high society. It was a world of social calls, dinners and dances, expensive gowns, fine carriages, finer homes and a lot of committees supporting worthy causes and charities. If Society expected Olivia to join them, they would be disappointed. Not because she didn’t want to be in that world, which probably didn’t hold much appeal to her, except for the charitable part, but her miserly husband made it difficult.

Their mansion was certainly not as large or well-appointed as he could have afforded. Russell didn’t see any need to spend money on it. Olivia therefore didn’t entertain. He also didn’t give her a generous allowance for clothing and accessories, as befitted her station. She was known to wear well-cared for clothing that was out of date and fashion, which may have also kept her from a great deal of socializing. Sage himself was well known to favor plain food and cheap clothing, to him both were just as good as gourmet meals and fine suits. He only indulged in his hobby of owning fine horses.

In their 37 years of marriage, she managed to squeeze only three large charitable donations out of him, all which elevated him and made him look good. He donated money to build Sage Hall on the Troy Female Seminary campus in downtown Troy. In actuality, he was against women’s education, believing it was totally unnecessary. As for higher education for anyone, he was quoted as saying that all any man needed was a grade school education and hard work to succeed. After all, that’s what he did.

The other two major donations his wife pressured him to make were to the Woman’s Hospital and to the American Seamen’s Friend Society. She teamed up with her close friend Helen Gould, Jay Gould’s eldest daughter, to build the Sand Street YMCA for Seamen near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. During Russell Sage’s life, Olivia’s charitable work consisted of what her biographer Ruth Crocker called “performative philanthropy.” She contributed what money she could, and volunteered everywhere. She headed committees for women’s suffrage, was the “lady manager” of the Women’s Hospital and sat on various committees to further women’s education at Troy Female Seminary.

Sage’s stinginess was legend. The NY Times would regularly have a story with yet another example of his tightness. One story complained that he allowed his 5th Avenue lawn grass to turn into hay, so that he didn’t have to buy hay to feed his horses. In 1902, a reader wrote in thanking the paper for providing yet another new story about “Uncle Russ.” Instead of gaining respect, he became a laughing stock. He didn’t care. He cried all the way to the bank.

(Editorial written after Sage’s death in 1906, NY Herald)

One day in 1891, when he was 75, Sage was in his NY office in the financial district. A man named Henry Norcross entered, saying that he was there to discuss railroad bonds. Norcross settled down with Sage and his clerk, then gave Sage a note demanding $1.2 million, or he would blow them all up. He revealed a bag of dynamite and a fuse. Sage angrily stood up and refused to pay, telling Norcross to get lost. But Norcross was serious and set off the bomb. Just before it went off, Sage grabbed his clerk, William Laidlaw and pulled him in front of him. The dynamite exploded, killing Norcross,, severely wounding poor Laidlaw and only slightly injuring Sage.

Disabled for life, Laidlaw sued Sage, accusing his employer of using him as a shield. After four trials, he won a judgement of $43,000, quite a large sum at the time. But a Court of Appeals reversed the judgement. Sage never paid Laidlaw a dime of settlement. He thought of it as a win, but NY society and the newspapers were quick to publicly criticize Sage and call him a cheap and heartless miser.

As the 20th century began, Russell Sage was now an old man. Olivia was over ten years younger than he was. He started to get sick and slow down and was unable to see to his finances as he once did. He didn’t trust anyone else and reluctantly handed his fortune over to Olivia to run. To his great surprise, she was not only competent, (that Emma Willard education) but excelled, with good investments that increased his fortune even more. In 1909, he was at his home in Sag Harbor, fell ill for the last time, and died at the age of 90. He left his entire $70 million estate to Olivia. In today’s money, that would be almost three billion dollars. 78-year-old Olivia Slocum Sage was now the wealthiest woman in America.

(Russell Sage Mausoleum, Oakwood Cemetery, Troy. Photo: Suzanne Spellen)

Olivia first needed to bury him. The Sage family plot at Oakwood Cemetery in Troy had only Marie’s obelisk rising at the top of the hill. Olivia had it moved to the side of the hill and had a large, very impressive Greek temple mausoleum built at the very top of the rise. It’s quite prominent and would be a fine resting place for a great man, except for one thing. She purposefully had no name inscribed on it. If one was visiting the cemetery and knew nothing about its inhabitants, one would never find Russell Sage.

The conventional explanation for not putting his name on it was that it would deter grave robbers. But no other prominent monuments were blank and Oakwood has some very wealthy families with very prominent mausoleums, which could also have been broken into. She also commissioned a stone bench to be placed at the side of the plot. It features a carving of the head of Medusa, the snake-haired figure from Greek mythology whose gaze turned men to stone. Olivia Sage had a wicked sense of humor.

She then turned her attention to all that money that Sage couldn’t take with him. He left no restrictions or instructions as to the use of any of it, and there were no heirs. He had worked so hard to accumulate it, cheating people, charging outrageous interest rates, playing hard and fast with railroad worker’s livelihoods, and ruining other businessmen. He never gave and only took. Mrs. Russell Sage, as she preferred to be called, changed all that. For the remainder of her life, she was dedicated to giving his vast fortune away.

Her first mission and great love was education. She gave her alma mater, the Troy Female Seminary, now renamed the Emma Willard School, a new location and a new campus; a beautiful Collegiate Gothic series of buildings built on a hill overlooking the city. That was in 1910. Six years later, she founded Russell Sage College for women on the old Emma Willard campus. Both institutions were dedicated to the higher education of women. Russell must have rolled in his mausoleum.

She also gave generous donations to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) in Troy, enabling the construction of a new dining hall and a laboratory, both with the Russell Sage name, and a women’s dormitory at Cornell University. She also bult a building for Vassar College, another women’s college. She established a teacher’s college at Syracuse University, demonstrating her love for her hometown and for the teaching profession. She also funded new buildings at both Yale and Princeton universities, and contributed to the National Training School in Durham, NC, which trained African American teachers.

She established a wildlife and bird sanctuary on Marsh Island in the Gulf of Mexico, and donated money for a new library in Sag Harbor, as well as the Pierson Middle-High School in the same town. Not all these donations were named after Sage, some, like the Sag Harbor school, were named in honor of her relatives and ancestors.

Her greatest financial contribution was to establish the Russell Sage Foundation for Social Benefit, which she set up in 1907 with a starter fund of ten million dollars. The foundation’s mission, as per her instructions, was to “be applied to the improvement of social and living conditions in the United States.” In the beginning, the fund gave modest amounts of money to poor people directly, but most of its work was in the advancing of the social sciences, studying societal problems and devising solutions that went to the core of those problems, not just the symptoms.

As a test case for developing housing, the foundation built Forest Hills Gardens in Queens, designed to be a completely contained new middle-class community. Society architect Grosvenor Atterbury designed it, but it ended up costing far too much, and was never affordable to middle class people. It remains a wealthy Queens enclave, beautiful, but technically, not successful in its initial goals. The foundation did not repeat the experiment.

Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage, Mrs. Russell Sage, became ill in her later years, and spent much of her time either at her brownstone in Manhattan or at her home in Sag Harbor. She died in 1918, having matched her husband’s lifespan of 90 years. In her will she left large gifts of $800,000 each to 19 educational institutions, in today’s funds, almost $15 million each.

She left the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Emma Willard School and the Women’s Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church more than a million dollars each and bequeathed the Russell Sage Foundation another five million dollars. She also gave many more smaller donations to many other causes, missions and organizations, including to the historically black colleges of Hampton and Tuskeegee Institutes.

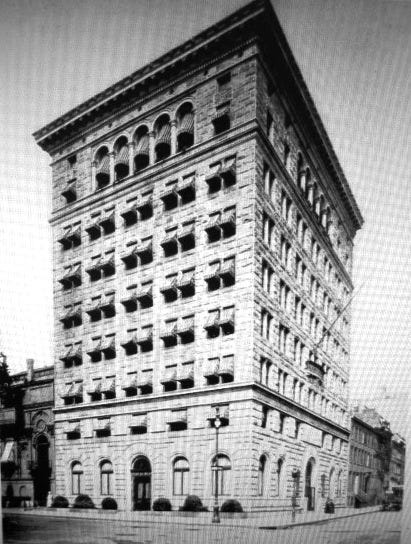

The Russell Sage Foundation is still operating, and still carrying on its mission of advancing the social sciences and support programs and institutions that work to better society. Its first headquarters was a Grosvenor Atterbury designed Beaux-Arts building on the corner of E.22nd Street and Lexington Avenue in Manhattan. Mrs. Sage had it built in 1912-1913.

(Russell Sage Building, 22nd St. at Lexington Ave. Manhattan. Photo: Wikipedia)

The foundation was housed on several floors and they offered office space at no charge to other social service organizations. It was fancier than many charitable institution’s buildings, as Olivia wanted it to be a special memorial to her husband. The building remained with the Sage foundation until it moved in 1981 to a Philip Johnson designed building on East 64th Street, where it remains. Today, the Atterbury building is a condo called Sage House.

One is left with the question of her relationship with Russell Sage. In her will she stated that she be buried in Syracuse with her parents, unlike many wives, she does not share the Troy mausoleum with her husband or his first wife. She put his name, not her own, on almost all of her projects, some of which, like Russell Sage College and the Foundation, remain prominent today. The mean old miser must have been spinning in his grave so fast, he could have generated enough electricity to light Troy for a century.

After almost 40 years of marriage, as frustrating and lonely as it may have seen, did they grow to love each other, or at least respect each other? Or was her naming everything after him a means of payback? Perhaps she felt this was a way he could atone for his life’s choices, as the Russell Sage money helped so many people and organizations over the last century. We’ll never really know, but Mrs. Sage remains one of the greatest philanthropists in the nation’s history. A great lady, indeed.

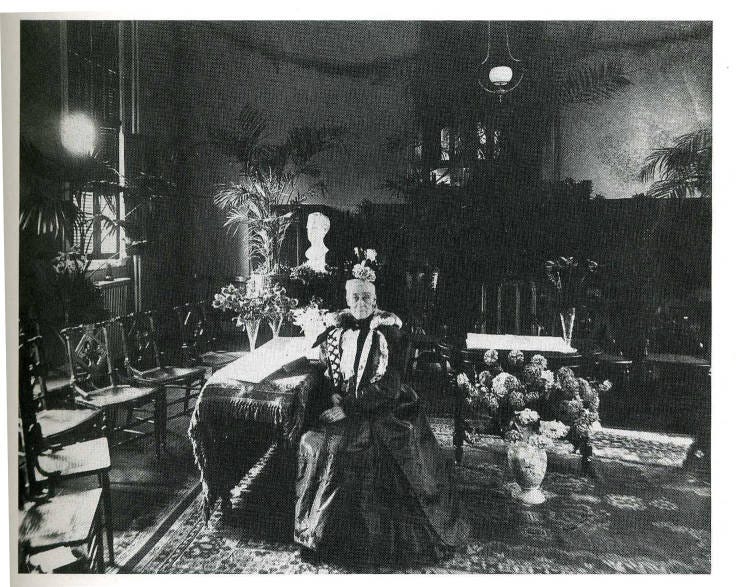

(Mrs. Sage at the NY Women’s Hospital, to which she gave generously. 1890)

A wonderful story! Thank you!

Thanks for filling in the gaps I didn’t even know existed! What a story and Olivia did so much for this country’s wellbeing! Well done. And thanks for the tour you have at The Troy Library. I could love to read your notes for that tour.