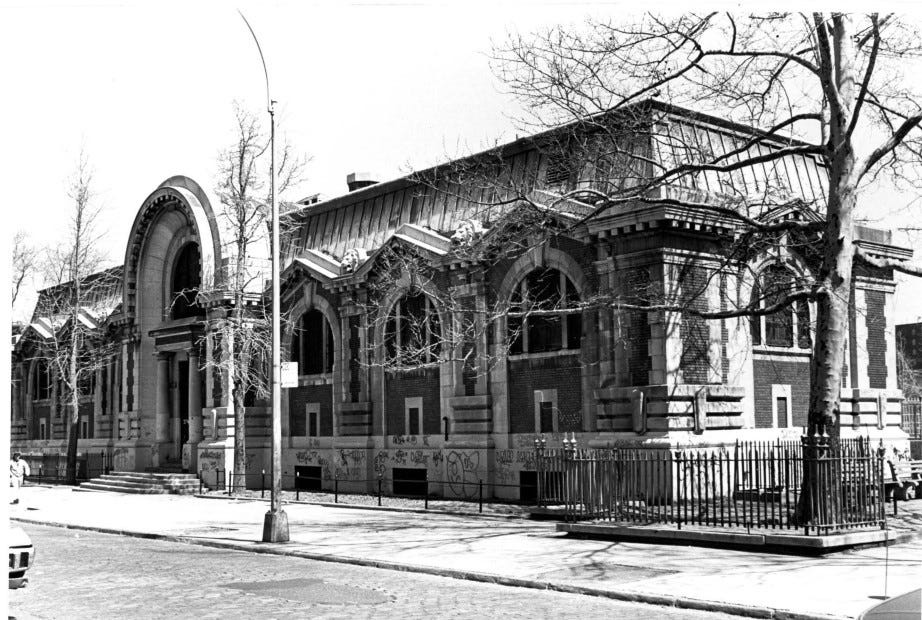

(Asser Levy Bathhouse, E. 23rd St, NYC. 1908. Photo: Wikipedia)

Whenever we get a particularly hot spell of weather, meteorologists and newscasters always compare it to a day in the past, when it was inevitably even hotter. Sometimes these record-breaking days are in the 19th century, or early 20th, long before air conditioning, or even the widespread use of fans. Our forebearers were tough people, wherever or whoever they were.

In New York City, the heat and humidity can sit like a physical weight, seeping into buildings and roasting the pavement and the streets. The summer streets were generally left to the poor and working classes in the summer, the rich got out of town, to a shorefront community or the country. Poorly ventilated buildings were like ovens, with no relief but the streets. What people wouldn’t give for a cooling dip in a pool.

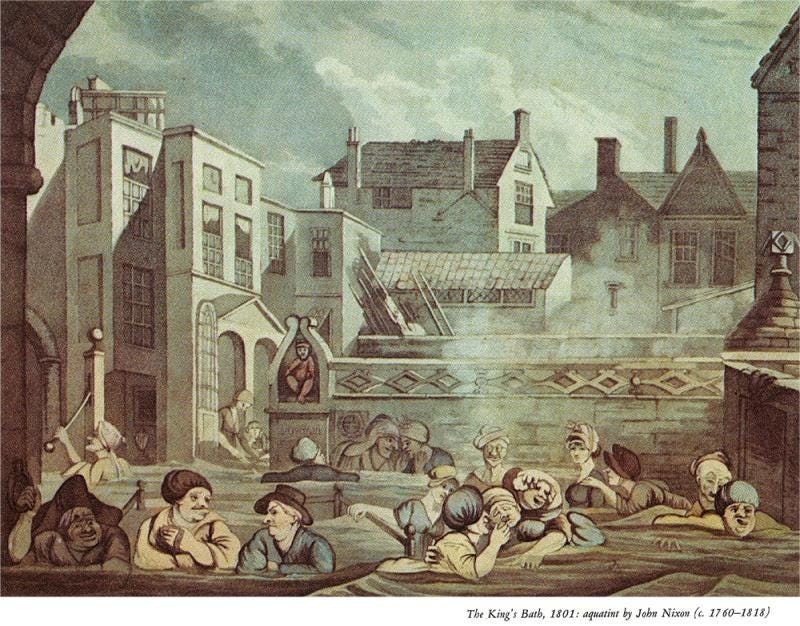

But we can’t talk about swimming until we talk about taking a bath. Believe it or not, in 1851, Millard Fillmore was the first American President to have a bathtub installed in the White House. He got flak from detractors for wasting the American people’s money on frivolities. The rich were used to “taking the waters” at spas and hot springs. But not even they were used to full immersion in a bath tub on a daily basis.

(The healing waters of Bath, England. 18th century.)

The European habit of going to public baths didn’t really catch on here, Americans have always been too private, and too prudish to bath amongst strangers. The advances in indoor plumbing in the 1840’s opened up a world of opportunities for private bathing among the well-to-do, but for the poor? Not so much.

By the Civil War, public health reformers were calling for frequent baths for good health. Catherine Beecher, the sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Ward Beecher, wrote that Americans should not only wash their faces, hands, feet and necks, but wrote, “It is a rule of health that the entire body should be washed every day.” By the end of the century, reformers were convinced that a person could not be healthy unless they were also clean; the two went hand in hand. And in those healthy hands should be a bar of soap.

Soap was far less common that one would think. Most soaps up to that point in time were manufactured for cleaning and scrubbing floors and clothing. This soap was strong and abrasive stuff. The gentle perfumed bars were for the wealthy, made by apothecaries and perfumers. A mild body soap wasn’t readily manufactured for the public until the end of the 19th century. As the popularity of soap for washing one’s body hit the middle classes, one of the first endorsers of Pear’s Soap was the Reverend Henry W. Beecher, who declared in an ad in 1885, “If cleanliness is next to Godliness, soap must be considered a means of grace.”

As the upper- and middle-class habits of personal cleanliness changed from the mid-19th century forward, they bolstered the attitude that cleanliness was morally superior. It defined intelligence, refinement and good breeding. The flip side of this was the dirt of poverty, defining ignorance, vulgarity and animalistic behavior.

The practical reality that those with means could afford indoor plumbing, bathtubs and soap, while the poor had none of these things, was lost on many who looked down their noses at the poor and the increasing amounts of new immigrants to the city. This conundrum was not lost on the dedicated reformers who pioneered the fields of public health. It took frequent cholera epidemics in large American cities to get those governments to authorize building public bath houses.

(Floating bath, NYC 1892. Photo: Columbia University)

Public bathhouses were common in European cities, with houses for both rich and poor, but in America, the first bathhouses were built and designed solely for the poor. New York City’s first was called the People’s Bath and Washing Establishment, built in 1852 at 142 Mott Street in Lower Manhattan by the New York Association for Improving the Conditions of the Poor. The facility had communal bathtubs for men and women, a pool, and laundry facilities. There was a charge to do laundry, or to bathe. It was very successful for a while but was closed in 1861 because of a lack of patrons. The simple fact was that it was too expensive for most of the really poor to afford.

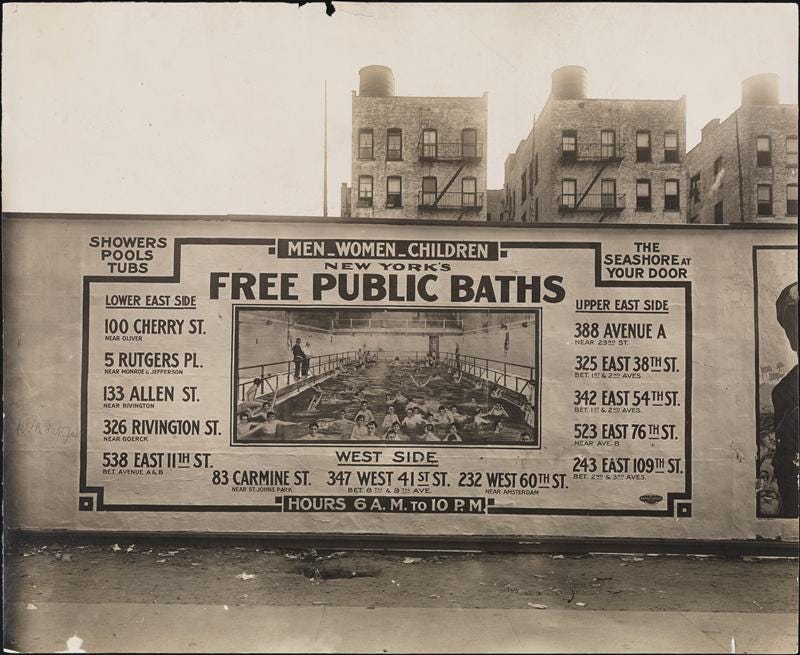

Reforms of any kind were put on hold during the Civil War, but from 1868 to 1878, the Legislature of New York State passed a number of laws authorizing New York City to build free floating baths on the Hudson and East Rivers, and at the Battery. The first opened in 1870, and by 1888, the city had 15 floating baths under the operation of the Department of Public Works.

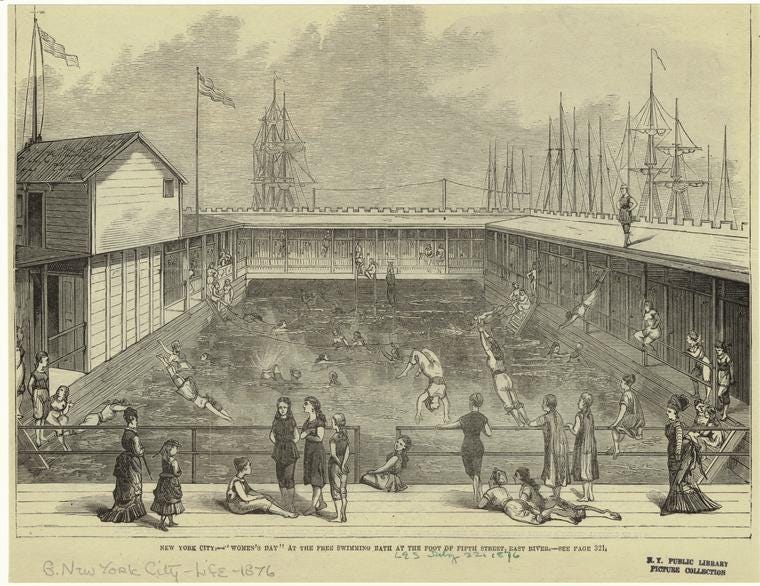

These baths were floating platforms on the rivers and bay, and used unfiltered river water, and were only open in the summer. They were divided into men and women’s sections, with dressing rooms and paths floating on pontoons. The floating pools of today, like the one moored on the Brooklyn waterfront in 2007, were based on this concept and design.

(Women’s Day at an 5th St. Bath. East River floating bath, 1876, via NY Public Library)

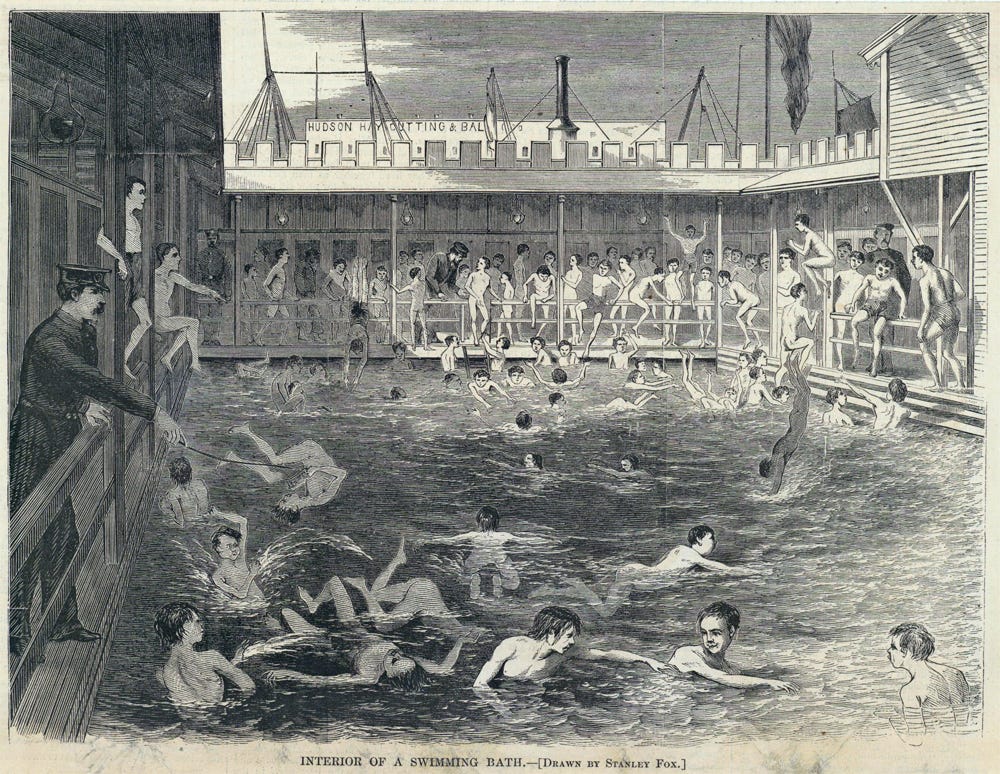

The floating baths were hugely popular with the poor, but were used to cool off and play in, not as baths for cleanliness, as designed. The authorities at these facilities limited people’s stay to only 20 minutes, enough time to get clean, not splash around. Some enterprising boys would go from pool to pool, getting dirty on the way, to be admitted.

(Another East River “Swimming Bath.” Boys generally swam nude until the mid 20th century. Illustration: NY Historical Society)

By 1914, the rivers had gotten so polluted from sewage that the baths had to be watertight, and the water filtered. While a boon in the summer for many, the floating pools did not address the need for year-round facilities for the poor to bathe in. The cry from reformers, the American Medical Association, and the New York City Board of Health was for year-round public baths.

In 1883, the New York Tribune editorialized that although it would be expensive, a series of public baths would in the long run, be a boon to the city. They suggested that the death rate would go down, as would the numbers of sick. They also suggested that a wealthy person donate a bath house, instead of an art gallery or library, saying that this would have a more lasting positive result on our society. Unfortunately, nothing happened and no one stepped forward. Public baths, paid for by the city, would not arrive until the dawn of the 20th century.

(A much later arrangement - 1935. Photo: Untapped NY)

It took partisan politics to do it. The Democratic machine, Tammany Hall, was against paying for public baths, saying that there was no public cry for it. This position held for three mayoral administrations, even though one of them, Mayor Thomas Gilroy, had been the head of the Public Works Dept. when the floating baths were inaugurated. Pro-bath people were sure he’d authorize the funding, but he toed the party line and sat on his hands, saying there was no demand. In 1892, the State passed a law mandating public baths to be built by municipalities across the state, but New York City ignored the law.

Finally, in 1894, sick of Tammany Hall politics, a coalition of reformers and Republicans got a reform mayor elected, Republican William L. Strong, a wealthy banker and advocate for many social reforms. He won handily, and among his many projects was to authorize a study for the building of city public baths, much to the disappointment of those who wanted to see the buildings built in a timely fashion, not just “studied.”

The study, which was a lesson in politics in of itself, did manage to recommend that many baths be built, as well as giving a recommendation that public schools install showers and baths for students. Unfortunately, Strong dithered around, and the baths were never built in his administration. It wasn’t until 1901 that the first public bath was built on Rivington Street, on the Lower East Side.

(Hamilton Fish Bathhouse, NYC. Carrère & Hastings, architects, 1898. Photo: Landmarks Preservation Commission)

In Brooklyn, the cry from the Brooklyn Eagle, in April of 1902, was, “We shall never have a beautiful city till we have a clean city, and the city will never be clean when masses of its inhabitants are dirty.” The editorial went on to urge the city to “build baths, big ones, handsome ones, and in every crowded quarter of the town.” The first public baths were built in 1903. By 1915, there were six, one on Hicks Street, Pitkin Avenue, Montrose Avenue, Huron Street, Duffield Street and Wilson Avenue.

Ironically, the grand building of public baths between 1903 and 1915 came too late. Many of these bath houses were spectacular pieces of architecture, designed by prominent architects. The Hicks St. bath in Brooklyn was designed by prominent Brooklyn architect, Axel Hedman. In Manhattan, the Beaux-Art bathhouse in Hamilton Fish Park was designed by the eminent firm of Carrère and Hastings. Most of the bathhouses were well appointed with excellent facilities and were well thought out and designed. But except for in the summer, none of them were used to capacity.

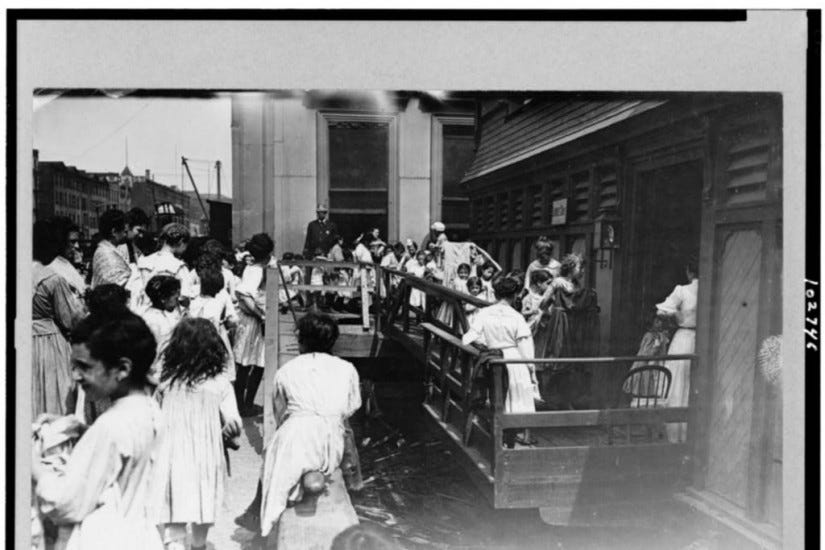

(Women and girls in line at a bathhouse. Photo: Library of Congress)

Long overdue progress killed the bathhouse movement. New tenement laws passed in the early 20th century mandated indoor plumbing. Many newer tenements also began to have bathtubs, first one on each floor, then in each apartment, albeit in the kitchen. Tenants began to demand them, and landlords had to supply tubs, or lose tenants. People didn’t need to leave home to get clean, and bathhouse use declined as the years progressed. Most of NYC’s public bath houses were re-worked by the WPA in the 1930’s, and turned into swimming pools or recreation centers, or torn down.

Public swimming pools? Well, that’s another story.

(E.11th Street Bathhouse, Manhattan. 1904. Photo: Wikipedia)

Waiting for that next other story! #FillThePool

Really interesting! I knew nothing about any of this. Thanks!