Talmage’s Tabernacle: A Brooklyn Story

The history of the city of Brooklyn is full of colorful characters. I wrote this story in 2012, and it remains one of my favorites. You can't make these people up.

Brooklyn was named the “City of Churches” because of the many fine church buildings that graced her streets. She was also famous for some of the great men who took to their pulpits and thundered down the Word of the Lord to their congregations. The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher was probably the most famous of these 19th century preachers, and his sermons and anti-slavery fervor made him world famous. But he was not alone.

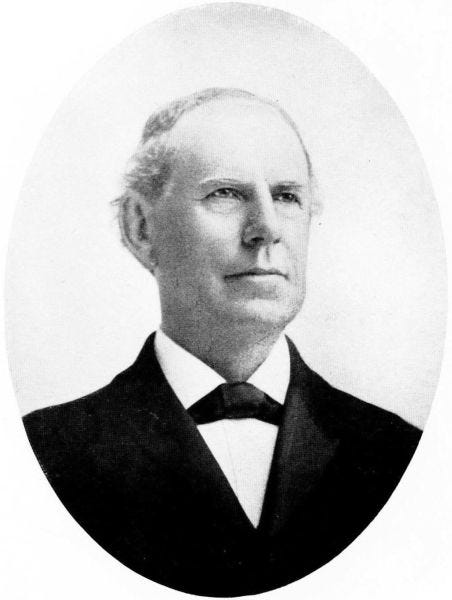

The second half of the 19th century saw the rise of several other famous preachers, with the Reverend Dr. Thomas DeWitt Talmage probably second only to Henry Beecher himself, in terms of popularity, and the size of his congregation. Rev. Talmage, like Beecher, was a charismatic man, a speaker of great oratorical skill, and could fill a room like few others. And, like his fellow clergyman, the Reverend Talmage’s triumphs, tragedies and tribulations were larger than life as well.

Thomas DeWitt Talmage was born in 1832, in Franklin Township, NJ. He got his degree at the University of the City of New York and studied law before deciding on the ministry like three of his four brothers. In 1862, Talmage became pastor of the Second Reformed Dutch Church in Philadelphia. It was here that he began to establish his reputation as a dynamic speaker and gifted preacher.

His sermons were often sensational and his delivery theatrical, causing him to be called a “pulpit clown” by his distractors, but his congregation didn’t care. They packed into the church, so much so that people had to be turned away into the street. His reputation spread outside of Philadelphia and in 1869, he accepted the job as pastor of the Central Presbyterian Church of Brooklyn.

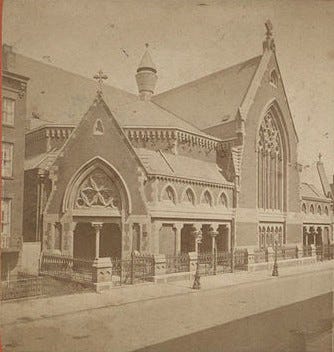

When Talmage arrived, the small church proved to be totally inadequate, with hundreds being turned away. They needed to build a bigger church. In 1870, a new church building went up in only three months, with funds quickly raised through Talmage’s popularity. This was called the Brooklyn Tabernacle, forever referred to as “Talmage’s Tabernacle.” The crowds grew even greater, three services had to be held on Sundays to accommodate them all. And still they came.

Talmage gave his congregation the must-have’s of successful preaching: sound theology well delivered, with theatrical pizzazz. No one fell asleep at Talmage’s Tabernacle. Although there were, and still are, dynamic preachers who literally scare the hell out of people with fire and brimstone pronouncements, Rev. Talmage’s sermons were instead much more intellectual, had practical and worldly references, and appealed to his urbane and sophisticated audience of Victorian-era Brooklynites.

A reporter from the NY Times recalled Talmage’s preaching style: “One Sunday morning when the time came for him to deliver his sermon, he walked to the extreme edge on one side of his fifty-foot platform, faced about, then suddenly started as fast as he could jump for the opposite side. Just as everybody in the congregation, breathless, expected to see him pitch headlong from the further side of the platform he leaped suddenly in the air and came down with a crash, shouting, ‘Young man, you are rushing towards a precipice.’ And then he delivered a moving sermon upon the temptations and sins of youth in a big city.”

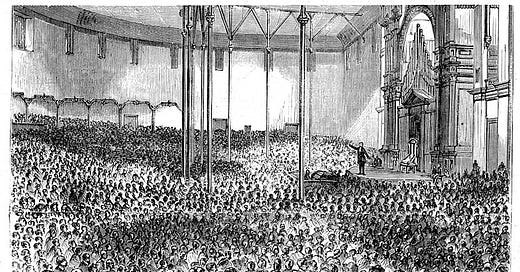

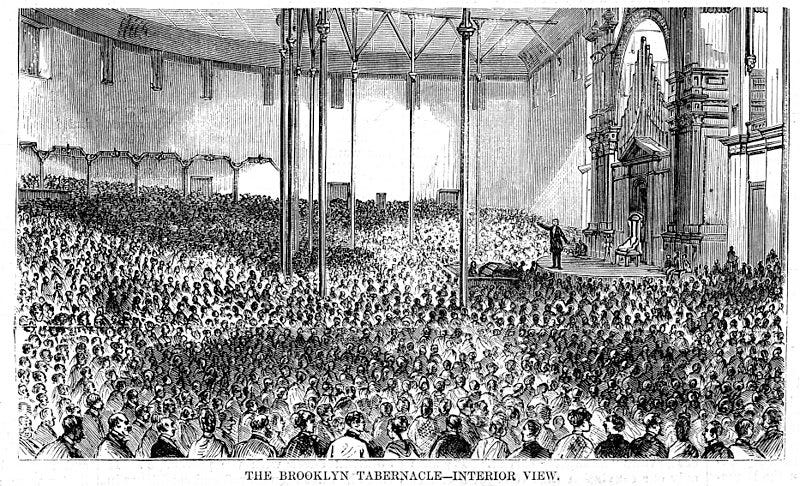

The Tabernacle itself was a different kind of church building. Like Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church, this was a preacher’s church, more auditorium than altar-bound sanctuary. The Brooklyn Eagle reported that the building resembled a concert hall, inside and out, with only a small steeple to denote a church. It was built for acoustic excellence and sightlines, not stained glass and flying buttresses.

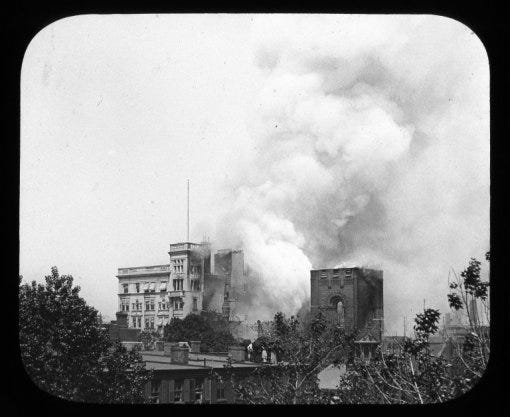

The eagerness to have the building finished in record time to house Talmage’s growing audiences contributed to some pretty shoddy building. Two years after the Talmage Tabernacle was finished, it burned to the ground in a spectacular fire just before Christmas in 1872, one of Brooklyn’s worst fires to date.

This fire took place as many made their way to services on Sunday morning, and fortunately, no one was trapped or injured. Later, it turned out that the building was a cast iron shell façade built over a wooden frame, resting on an older wood-clad foundation. All the interior furnishings, including the large number of pews, were wood, and the building was a tinderbox looking for a spark.

Talmage and his congregation were devastated but wasted no time in announcing that a new church building would be built on the ashes of the old. In the meantime, they moved their services over to the Brooklyn Academy of Music, a large concert hall on Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights. They stayed there until 1874, when the new church was finished.

Architect John Welsh’s new church for Talmage could seat 5,000 people. The pews were arranged in a semi-circle, pointing to the stage and pulpit, with several galleries and balconies to accommodate everyone. The center of the stage was backed by the largest organ built for a church in Brooklyn at that time. This wonderful new building opened for business in 1874, with the Reverend T. DeWitt Talmage at the pulpit, backed by his popular organist, George W. Morgan, “exercising his musical muscle,” as the Brooklyn Eagle enthused. Talmage’s Tabernacle would go on.

The years between 1874 and 1889 started off well enough, with church membership growing every week. Reverend Talmage was now one of the most famous preachers in the United States. His lectures were published in book form and as single articles, distributed across the country and in Europe. His congregation was growing every day, and he was being called on to give advice to the famous and speak to congregations great and small.

But as we all know, when all is going well, a wise man looks for trouble. In 1878, trouble came to call, and it announced itself throughout the Tabernacle in a loud crash of discordant organ music.

People came to the Tabernacle to hear Talmage preach, but a good church service needs more. Music was an important part of the service, giving the congregation a chance to participate as well as listen, and Talmage was on record as saying that in his opinion, the only way to praise the Lord though music in his church was with an organ and a coronet blasting the music of God to the heavens. The first Talmage Tabernacle featured a huge pipe organ that was bought from the Boston Coliseum. At its keyboards was Mr. George W. Morgan, one of the 19th century’s most accomplished organists.

Today, Morgan is included in many lists of the great organists of the 19th century. He was hired by the Tabernacle specifically to play the National Peace Jubilee and Music Festival organ, a massive instrument built for the Peace Jubilee, a celebration of the restoration of the Union, held at the Boston Coliseum in 1869. The Tabernacle purchased the organ and had it rebuilt in the church. It was said to literally rattle the walls when Mr. Morgan pulled out all the stops. It must have been magnificent.

The fire in 1872 destroyed this organ, along with everything else. The second Tabernacle’s organ was even bigger than the Peace Jubilee organ, with three keyboards, a 30-note foot pedal organ, 2 ½ octaves of bells, 43 stops and 42 ranks. This was a big, powerful musical instrument that needed a master organist, capable of reading a complicated score while playing three 58-note keyboards with his hands while simultaneously playing another full keyboard with his feet. This was not the minister’s wife gamely plodding though a hymnal. Watching and listening to Morgan play was worth coming to church for, all by itself.

Morgan was handsomely compensated for his work, with a salary of $2,200 yearly, which was reduced in hard economic times, with Morgan’s approval, to $1,800 a year. He had plenty of outside work. The Tabernacle had a large board of trustees which took care of the everyday business dealings of the church, to relieve the Great Man to do Great Things. In 1878, the trustees, who had the power to hire and fire employees, decided to fire George W. Morgan. Before you could say “Bach Toccata and Fugue,” the battle was on.

This happened in the summer and both Rev. Talmage and Mr. Morgan were vacationing. Morgan was with his family in Newport, RI, staying with friends. When he came back on September 1st, he found out he was unemployed. Talmage was also back from vacation, and he promptly had a few conversations with the board, and Morgan was reinstated.

But the next year, the board tried firing Morgan again.

In February of 1876, the board sent Mr. Morgan a letter, telling him negotiations for his contract would commence. They wanted him to take another cut in pay, reducing his salary from $1,800 to $1,200 per annum. (All this while membership in the church was rising at the rate of 500 new people per month.) He sent them a letter saying he wanted to wait for Talmage to weigh in, but then sent another letter saying he’d take the pay cut. Two days later, he received a letter telling him that after his contract expired in May, his services were no longer required.

Talmage came back from his trip and was told about the decision. He immediately called for a meeting of the Board of Trustees and the Elders of the Church. What resulted was a very messy power struggle, and in the words of the Brooklyn Eagle, “the boys (trustees) gave themselves away very badly.” After a lot of ecclesiastical wrangling, and probably some very un-Christian behavior, the trustees had to back down, and re-hire George Morgan, at his present salary, as well as a Mr. Gulick, who led the congregation in singing, who had also been canned.

The entire trustee board quit. The first thing they did was go to the Eagle and voice their complaints in the form of a very long letter explaining their actions. They voiced their support of Rev. Talmage, despite his “grave errors” in this matter, and made reference to Mr. Morgan’s talents, despite his “faults”, which they had so generously overlooked the first time they fired him but couldn’t overlook the second time.

A separate letter from Mr. Pearsall, the Secretary of the Board, revealed more dirt. He said that Mr. Morgan often came to the church intoxicated, and was drunk during services, so drunk he couldn’t walk. He said that Talmage had complained about it often, but had also overlooked it, saying that Morgan was “a better organist drunk than any other organist sober.’’ Morgan’s re-instatement, achieved by tossing out the church bylaws, was why he and the whole board had quit.

They may have been moral, and they may have been right to do so, but no one cared. Morgan was back in front of his organ, perhaps drunk as a lord, perhaps not. Gulick was leading the congregation in song and Talmage was at the pulpit.. The church was still growing, and the new Board of Trustees and Elders voted to give Talmage a substantial raise for 1879. However, back at Presbyterian Church headquarters, far above Rev. Talmage’s head, that sage body did not like their preachers ignoring church by-laws whenever they chose, no matter who they were.

Word of this incident reached the Presbytery, the governing board of the Presbyterian Church, and charges of falsehood and deceit were placed against Rev. Talmage. He was ordered to appear before an ecclesiastical court. The day of the trial brought out not only Talmage’s supporters and accusers, but the press and representatives from almost every denomination in Brooklyn, as well as Manhattan and even overseas.

The Presbyterian church chosen for the trial was packed to the rafters. Talmage entered with his wife, seated her with supporters, and sat in a pew with his advisors. After the rest of the panel was seated, including a blind clergyman who had to be escorted to his chair, (great dramatic move, there) the meeting got down to business. Many people testified against Rev. Talmage, but no one was able to really prove that he had lied about anything or had gone against church doctrine.

After much deliberation, the Presbytery of the Church declared that no evidence existed to show that Dr. Talmage had lied, misrepresented himself, or had otherwise done any wrong. He was cleared of all charges, his church was still his church, and he was able to go back to his pulpit. They just asked him to tone down the sensationalism.

By the end of the 1880s church expenses grew, causing the trustees to wrangle with their debt. There were suits and countersuits by church members claiming they had not been paid back for loans to the church. Then, on October 13, 1889, it happened again. The second Brooklyn Tabernacle burned to the ground.

If your church burns down once, it can inspire a congregation to build again; larger, stronger and better. If the new building, in the same location as the first, burns down fifteen years later during a violent thunderstorm, you might take it as a sign that it’s time to find another part of town to build in. This is exactly what the minister, board and congregation of the Brooklyn Tabernacle thought after Talmage’s Tabernacle burned to the ground for the second time. The first two churches had been on the edge of Downtown Brooklyn. After a search for a suitable property, it was announced that the third Talmage’s Tabernacle would rise on Clinton Avenue, in the heart of fashionable Clinton Hill.

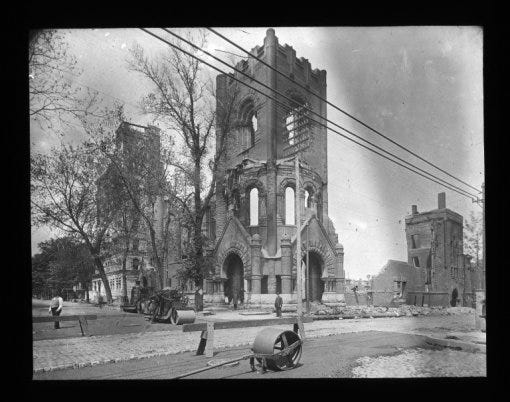

Rev. Talmage told the press that there seemed to be “a fatality about the location” and he and the congregation retired once again to the Brooklyn Academy of Music until the new church could be built. The third Tabernacle, like the second, was designed by architect John Welsh. It was a large brick, sandstone and granite Romanesque Revival style church, with a tall, thick bell tower that rose over that part of Clinton Avenue. The cornerstone was laid on Oct. 28, 1889, and signaled the beginning of a new church, and a whole new bunch of problems for Talmage and his flock.

The church cost $400,000, a massive sum for the time, and they didn’t have it. By 1890, there was a mechanics lien on the building for work that had not been paid for, and construction had halted. Talmage assured reporters that the church would be finished and dedicated by Easter of 1891. The church had insurance from the last building, collections, a building fund, fundraisers, they even got donations from other churches, but it just wasn’t enough. In September of 1890, they filed papers with the courts to take out a mortgage on the property, which would be held by Manhattan financier Russell Sage.

Sage agreed to lend them $113,000 to finish the church. Russell Sage was a notorious skinflint, and probably only lent the church the money because his wife leaned on him. Olivia Slocum Sage was a generous philanthropist and a very religious woman. Sage was a businessman. He charged the Tabernacle 6% interest on the loan. The hard-working trustees of the church issued bonds to raise even more money. The bonds were backed by a mortgage of another $250,000 on the church and property. The Tabernacle was running solely on faith, not cash.

Of course, money or no money, Talmage wasn’t going to go cheap on the furnishings of his new church. For the new Tabernacle, he ordered a $30,000 Jardin organ, five times as expensive as most church organs. The second Tabernacle organ had three keyboards, this one had four, plus a 2 ½ octave foot pedal keyboard. This magnificent instrument would be the second largest organ in America, surpassed in size only by the organ in the great Chicago Auditorium. The longest pipe in the system was 32 feet long, the same as the longest pipe at Westminster Abbey in London. All in all, the organ would have 66 stops and a whopping 4,448 pipes.

The third Brooklyn Tabernacle was up and running in the spring of 1891, as Dr. Talmage had predicted. There were still some details to finish, but the church, which had which had garnered a lot of NIMBY resistance, was conducting Sunday services, as well as weekday lectures, concerts and meetings.

The enormous church seated 6,000 people and could fit another 2,000 in standing room. It had one of the largest pipe organs in the Western world, and a 200-voice choir. Only the Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City, which could hold 10,000 people, was bigger. Despite the neighbor’s trepidations, the church proved to be an economic draw for the neighborhood. In 1891 a luxurious new hotel called the Regent was built right next door to the church. But the church’s money problems persisted.

During a prayer meeting at the church one Friday night in December 1892, sheriff’s marshals came in and seized the building. An interior decorator named Alfred R. Tong was suing the church for non-payment of $1,104.88, for work done in the Tabernacle, and had won the judgment. He was going to get his money from the collection plate if he had to. The church needed another quarter of a million dollars, and the treasurer reported that they were barely paying their running expenses.

At the height of this financial crisis, Dr. Talmage announced that he might have to resign, as it was all too much for him to deal with. He hinted that other churches were eager to hire him. He told a reporter that “These money troubles of ours oppress me. They interfere with my work. I have often said that I have but one real trouble in life and that is the conditions that beset the Tabernacle. The truth is that the person who occupies the pulpit in a church needs to conserve all his mental forces for his Special Work.”

On March 3rd, 1894, Rev. Talmage announced that he would leave if the financial problems of the church were not resolved by March 22. He put in his resignation, saying that “the constant uncertainty as to the continued life of the church embarrassed him in his work, and he thinks that he is not called upon to stand the strain any longer.”

Brooklyn rallied about the Tabernacle, with charity events and fundraisers held to benefit the church. No one seemed to want to lose the Rev. Talmage. By 1894, thousands of dollars had been raised, within and beyond the church, holding the wolf of debt at bay. But that soon would not be a problem. Or not the same kind of problem, anyway.

May 13th, 1894 was a Sunday. Reverend Talmage was getting ready to leave Brooklyn on another lecture tour and he and his wife were greeting the last of the congregation after services. Suddenly, one of the church members remaining in his pew noticed smoke coming from behind the altar. In no time, the back of the church went up in flames, and the Talmage’s, the organist, and remaining members barely escaped from the church.

As a growing crowd gathered and the fire wagons arrived, the entire building was engulfed in flames. By the end of the day, the third Brooklyn Tabernacle was an empty burned out shell. Lost in the fire were thousands of dollars’ worth of furnishings, the second largest pipe organ in America, and a whole lot of debt.

The Lord works in mysterious ways.

Not only did the fire destroy the third incarnation of the Brooklyn Tabernacle, but it also destroyed the brand new Regent Hotel right next door, as well as caused damage to at least twelve other buildings in the immediate vicinity, including another church a block away. It was a conflagration of Biblical proportions, fed by flammable materials and a strong wind that blew burning cinders for blocks.

In the aftermath of the fire, the most astonishing revelation of all emerged. The interior walls and ceilings of the Tabernacle were not plaster, or fire-resistant asbestos, or even wood, as was thought. They were a manufactured wall covering called “artificial lumber”. And what was artificial lumber? Macerated straw pulp and pine resin, heated and pressed into boards and decorative ornament. You can’t get more flammable than that.

Added to that, the gorgeous and magnificent organ, with its over 4,400 pipes, channeled the heat and fire through the building like an array of chimneys, funneling the fire like a bellows. Plus, the church had large swaths of heavy velvet curtains and draperies, especially near the altar and organ. It was a perfect storm. An investigation would be carried out to see if this highly flammable material had been in the plans, and if the Buildings Department had approved it. Or had a cheap switch been made, figuring no one would ever know? Did Talmage know?

After the fire, while the ruins were still smoking, Talmage announced he was leaving town for his speaking engagements on the Continent and in Australia. In a long rambling letter to his congregation, reprinted in full in the Brooklyn Eagle on June 9th, 1894, Talmage spoke of the cleansing fire that consumed the buildings of man. He questioned if some of his congregants weren’t idolizing the building itself, placing too much importance and glory on its splendid appearance and its mighty organ.

He spoke rapturously of that incredible musical instrument, eulogizing it thus: “An organ that was a hallelujah set up in keys and banked in pipes, waiting for a musician’s manipulation that would lead a congregational song as an archangel might lead heaven. Glorious organ! When it died down into the ashes of that fire perhaps its soul went up where Handel and Hayden began to play on it.”

The man could certainly turn a phrase. He could also turn his back on the people who had supported him and made him who he was.

He wrote of his meetings with presidents and kings, and trips that took him to the corners of the earth. How he, a mere farm boy had risen in the world. Like any good narcissist, Talmage only saw how the fire affected him personally. The destruction of two buildings, the frightening near-death experiences of the guests of the Regent Hotel who escaped with only the clothes on their backs and the damage to many other structures in the neighborhood was part of the Divine plan just for him. The fact that the church still owed hundreds of thousands of dollars to creditors didn’t mean much to him either.

He wondered if God was telling him that he should be humbler. “There was a danger that I might become puffed up and my soul be weakened for future work,” he reasoned. He ended by saying that perhaps God was cleansing by fire his most important instruments, the people of the Brooklyn Tabernacle. They would be made stronger and better. He didn’t know what God had planned but he was confident that it would be revealed to them. It was too bad he wouldn’t be there.

He would, of course, write to see how they were doing.

He officially resigned on November 5, 1894.

The Trustees and church members met to decide what to do next. They considered rebuilding and finding a new preacher. The congregation met at a local theater for services, and their interim pastor read a letter from Talmage, who was checking in while doing God’s work on the Continent. Only 300 people showed up, and when the letter was read, it was met with dead silence.

The congregation of the Tabernacle slowly broke up, with members joining other churches. The burned-out hulk of the church became a neighborhood draw, the ruins almost as popular as the church had been. The site was sold and upscale housing was built several years later. The trustees stayed together long enough to wrap up business and settle the debt as much as they could.

In August of 1895, Talmage’s wife of over thirty years, Susan Whittemore Talmage, died in their home in Brooklyn. Mrs. Talmage was much loved, and her funeral brought her husband back to Brooklyn for the first time in years. Susan Talmage had been from a wealthy family and at her death Talmage received her fortune, setting him up financially for life. He would later raise eyebrows by marrying again, three years later. His new wife Eleanor Collier was a 40-year-old widow. Talmage was 67 at the time, the father of five grown children.

After lecturing on the road for a few years, Talmage decided to go back to pastoring a church, and became the associate pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Washington DC. He brought in large crowds, but nothing like the ones he had had in Brooklyn. Times were changing and his style of preaching was no longer as popular. He returned to DC from a trip to Mexico seriously ill and died from inflammation of the brain on April 12, 1902. His funeral was a quiet one, and his family received condolences from all over the world. Reverend Talmage is buried in the family plot in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.

The questions remain. Was Rev. Talmage responsible for any or all the fires? All happened on a Sunday when he was there. Did he set the first two to force his congregation to build larger and better churches? The third fire was a result of faulty wiring in the organ. Was it carelessness, or a bold attempt to get the church out of debt? They were, after all, holding a massive amount of debt. Who had authorized the flammable building materials? Someone had to know they was up there. Or was Talmage’s ego so big that he thought he could be God’s instrument of cleansing fire? We’ll never know.