The Age of Electricity and the Unknown Story of Louis H. Latimer

Edison's great achievements would have been much less without the genius and talent of a hugely overlooked son of slaves.

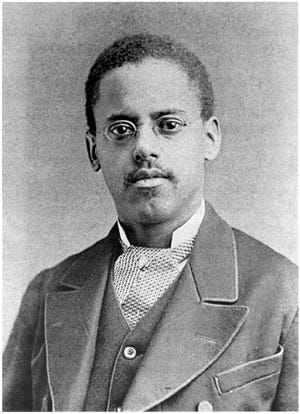

(Lewis Howard Latimer, via Wikipedia)

HBO’s new period show, “The Gilded Age” had a recent episode where industrialist George Russell had a grand ceremony to light the New York Times building in Manhattan with electric lights. Hundreds of people, from working class to high society, black and white, gathered in the square to count down to the moment that the lights came on, slowly, from the ground floor to the dormers at the roof. It was a magical moment, and when all the lights were on, the people gasped in wonder and applauded. (This scene was staged in Troy’s Monument Square, with some added special effects and CG.)

While everyone was lauding Thomas Edison, who was standing next to Mr. Russell, two of the African American characters in the show crowded in along with everyone else. They mentioned that although Edison’s work with electricity was groundbreaking and awesome, there would have been no long-lasting incandescent lightbulbs had it not been for the invention of a black man - Louis Latimer, who invented the long-lasting carbon filament that revolutionized light bulbs.

“Would Mr. Latimore be up on the dais with Mr. Edison,” one character asked the other. “Surely his inventions in electricity would be celebrated!” They then answered their own question – not likely. And no, he wasn’t there. Louis Latimer was not a fictional character, he, like Thomas Edison, was quite real.

The next time you go into a bathroom on a train, or turn on the air conditioning, take an elevator or more importantly, the next time you turn on an electric light, you should thank an African American inventor named Lewis H. Latimer. None of those things would have been possible in their present form without his inventive mind, yet he remains unknown and off the list of the great American inventors.

Did you learn about him in elementary school? Is he a household name like Thomas Edison, with whom he worked closely, and called a friend? No. The fact that he is more or less forgotten by most is one of the great flaws in our selective history. Why isn’t he up there with Edison, Bell, Otis, Westinghouse, Firestone, and the other greats of the 19th and early 20th century?

Lewis Howard Latimer was the son of slaves. His father George had been the property of a slave owner in Virginia named James B. Gray. His mother Rebecca was owned by a different slaveholder in a nearby household. Vowing never to bear a child into slavery, Rebecca Latimer devised an escape plan. George was very fair skinned, fair enough to pass for white. He would pose as a master and travel north with Rebecca as his servant. It worked. In 1842 the couple headed north from Norfolk, Virginia and eventually made it all the way north to Boston, a hotbed of Abolitionist activity.

Rebecca and George had four children, all born into freedom. Their youngest child, Lewis Howard, was born on September 4, 1848. In 1860, when Abraham Lincoln was elected president, Lewis was 12. The Civil War started a few months later. Massachusetts was one of the first states to have African American regiments, and Lewis’ older brothers immediately signed up with the Army. When he was 16, Lewis enlisted in the Union Navy.

Returning from the Civil War, Latimer felt that America would allow his people to assume their rightful place as American citizens. He thought the bravery and patriotism shown by the black soldiers would convince America that they were worthy. He was proud of his service, and in later life, became an officer in the Grand Army of the Republic, the Civil War veterans’ organization. He would wear his GAR uniform with pride on many civic occasions. But he was wrong about America. It was not ready for equality.

Back now in Boston, Lewis was looking for work. A black woman who cleaned in a copyist’s office told him that a patent law firm was looking for a black office boy. He would be working for the office’s draftsmen, who drew the drawings of client’s inventions for patents. One of the prerequisites of the job was that he would have to have an affinity for drawing. Lewis had always liked drawing, so he applied for the job and was hired.

While cleaning up and running errands, he took the time to watch the draftsmen. He took notice of their tools and what they were doing with them. Going to a secondhand book shop, he bought a book on drawing and the drafting trade and purchased some used drafting instruments. After his days at work, he spent his nights teaching himself how to draft. He continued to watch the men in the office, and then went home to practice. He mastered the craft and decided it was time to test it out. One day he asked one of the draftsmen if he could give a project a try.

The draftsman laughed at the thought but allowed Lewis to give it a shot. He sat down and showed he was a true draftsman. His employers at the firm, Crosby & Gould, saw his work, and allowed him to continue, and soon realized that Lewis was as good, if not better, than everyone in the shop. They hired him as a draftsman, increasing his salary from $3.00 a week as an office boy, over time to $12 a week as a draftsman. He stayed with the firm for eleven years.

Now making a living wage, Lewis was able to get married. He and his bride, Mary Wilson were married in 1873. They would go on to have two children, Emma Jeannette, born in 1883, and Louise Rebecca, born in 1890.

Working at the patent office gave Latimer an opportunity to see how the process of invention worked. He realized that most inventors did not come up with their inventions out of nowhere; they all improved on the ideas or products of others. An invention was more likely to be an evolutionary process, rather than a “Eureka” moment, where an idea came out of the blue.

He realized that he had this same knack; the ability to see a product or idea and know what the next step was. He could make what someone else had come up with even better. This process is at the core of our great inventions, from Bell to Edison to Jobs to Gates.

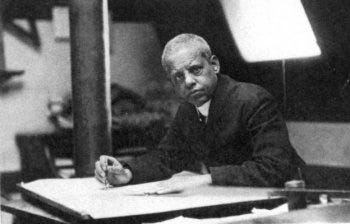

In 1885, Lewis began working for Thomas Edison. He first became a member of the engineering department at the company’s Manhattan headquarters at 42 Broad Street. He worked in this capacity until 1890. He was out, front and center in the department, doing what he did best, drawing the devices and electrical systems that would make Edison the leader in electricity. But while he was all about the work, some of the workmen still couldn’t believe they were seeing a black man in his position.

He had to take the time to prove himself to almost every new workman and new hire in the company. Some just couldn’t believe he could do the work and didn’t want him near their projects. They couldn’t believe a “colored man” would be in his position, and he had to patiently prove to them that he was an expert in his field. One by one, he won them over by his expertise, and they soon realized that not only was he good, but his abilities were also far ahead of almost anyone else in the field, period.

In 1890, Latimer was hired in the legal department of the Edison Electric Light Company as the chief draftsman and patent expert. The growing field of electrical studies meant that new inventions were appearing literally every day. Inventors, including Thomas Edison, were being inspired by other people’s innovations, and they, in turn, would use those innovations to spring off into a new direction.

Like computer technology today, electricity was an exciting field to be in, but if someone wanted to make money by marketing the technology, they needed to make sure their inventions were unique, and could be patented to protect them from being copied, and they needed to be able to do it fast and accurately. Latimer was an expert in that end of the invention process. Edison’s hugely inventive mind, along with the talents of his assistants and staff, meant that the Edison Electric Company had a lot of patents to file.

Lewis was such an expert now in electricity and electrical systems that he too was able to join the invention process and came up with innovations that were also patented. He invented a new carbon filament for light bulbs that extended their lives, while working for Edison. He not only drew these inventions, but he also understood them, which was invaluable to the company. He was often called as an expert witness in the many patent trials that took place at this time. Everyone was suing everyone else, in long drawn-out lawsuits. The stakes were high, as winning meant the difference between financial success and ruin.

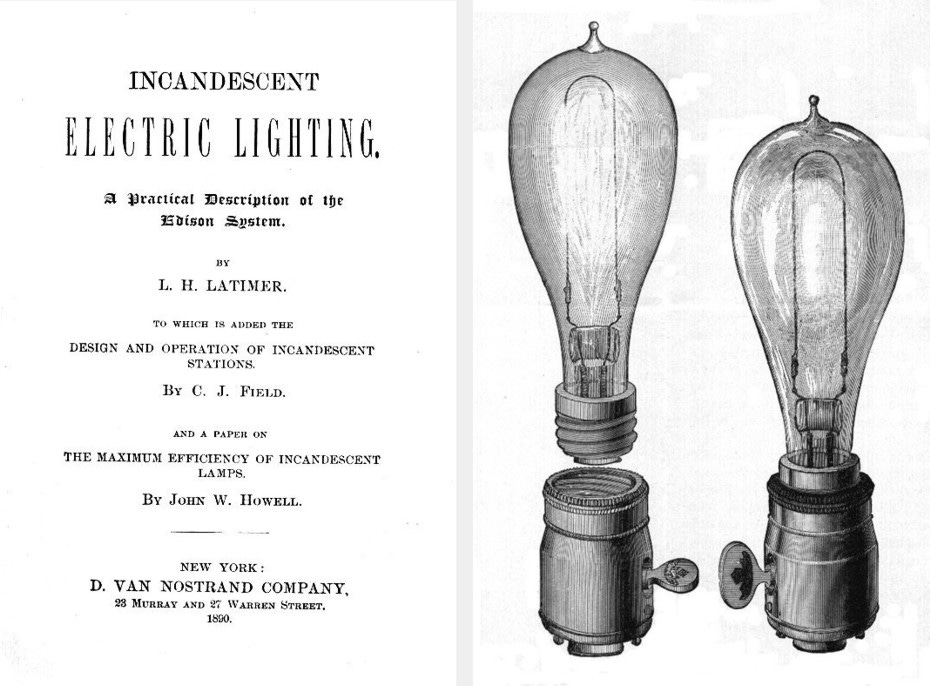

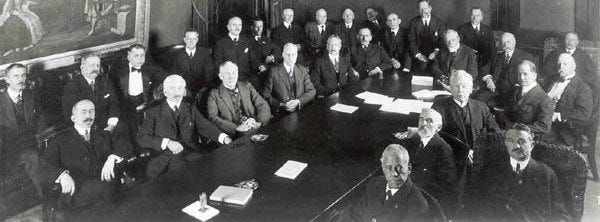

Latimer found himself on the witness stand often, defending Edison’s inventive processes and results. The same year he moved to the legal department Lewis wrote the most thorough book on electrical lighting to date. It was called “Incandescent Electric Lighting: A Practical Description of the Edison System.” He was named as one of the Edison Pioneers, an elite and distinguished group of people who were hailed as being responsible for creating the electrical industry. He was the only African American in the group of 28. He considered Thomas Edison a friend and mentor, and always spoke and wrote very favorably of him.

(The Edison Pioneers. Louis Latimer is in the foreground. Photo: Spark Museum)

In 1896, after years of protracted law suits, the Edison and Westinghouse Companies came together to form the Board of Patent Control. The advisory board’s purpose was to coordinate their future licensing and avoid expensive lawsuits. Latimer was asked to join the board, where he became its chief draftsman and full-time patent consultant. He was still busy inventing things on his own and applying for new patents. Earlier in 1894 he created a new safety elevator, an improvement on all existing elevators.

He received a patent for his Locking Racks, a device for holding hats, coats and umbrellas. The device could be installed in public places like restaurants and hotels and held the items securely against being misplaced or taken by mistake, or stolen. He invented an improved book supporter that kept books upright on shelves. He also came up with an early version of the air conditioner with the first HEPA filter. He called it an “Apparatus for Cooling and Disinfecting.” It was used in hospitals to prevent dust and particulates from circulating in public areas of the hospital, as well as in patients’ rooms.

In 1903, the Latimer family purchased a home in the predominantly white neighborhood of Flushing Queens. The house was on Holly Street. It wasn’t a fancy house, but a relatively new Queen Anne suburban cottage built between 1887 and 1889. The house had been constructed by, and for a family named Sexton. Lewis would live there for the rest of his life.

Latimer was a firm believer that the Constitution, if followed, demanded social justice for black people. He met with many of the black intellectuals of the day, including Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and Richard Theodore Greener. The latter was the first African American to graduate from Harvard. Greener was a scholar and diplomat, and one of the organizers of the National Conference of Colored Men, which took place in Detroit in 1895.

The Latimer household became a gathering place for many of the leading black cultural and political leaders of their day. The poet-composer James Weldon Johnson, his brother, composer J. Rosamund Johnson, composer Harry T. Burleigh, actor and singer Paul Robeson and writer and activist W.E.B. DuBoise, among others, were all guests at the Latimer house. Louis was also an accomplished poet, himself. His wife and daughters were fine classical musicians.

In 1911, the Board of Patent Control dissolved. Latimer once again found himself without a job, and no prospects. Despite his reputation and skills, he was not able to get a job until he was hired by an old friend and colleague, Edwin Hammer, another of Edison’s Pioneers. He became Hammer’s patent consultant until 1922, when ill health caused him to retire at the age of 74. He died on December 11, 1928, at the age of 80. The Edison Pioneers published an obituary. It read, in part:

“He was of the colored race, the only one in our organization, and was one of those to respond to the initial call that led to the formation of the Edison Pioneers, January 24th, 1918. Broadmindedness, versatility in the accomplishment of things intellectual and cultural, a linguist, a devoted husband and father, all were characteristic of him, and his genial presence will be missed from our gatherings.”

The Latimer home passed to his daughters, Louise Latimer and Jeanette Latimer Norman. After their deaths, the house passed to others and finally to a developer in 1988, who wanted to tear it down. A Save the Latimer House Committee was formed to move the house. The house was moved to a safe location in 1994 and set on permanent foundations.

It was ceded to the Department of Cultural Affairs which now runs the Lewis H. Latimer house as a house museum, under the direction of the Historic House Trust. The house is a repository of Lewis Latimer’s life and works, as well as the works of other black inventors and scientists who have been left out of the pantheon of America’s great inventors and innovators. It’s a museum worth visiting, not just for African Americans, but everyone.

In real life, as well as on “The Gilded Age,” Louis Latimer should have been on that stage.