The Architect, the Baseball Stadium and a Really Bad Couple of Years

Ebbets Field was one of the most famous ballparks in the world, a symbol of Brooklyn. But the man who designed it is totally forgotten. This is his story.

(Ebbets Field, 1913)

Some of Brooklyn’s greatest architectural treasures were designed by people whose names we either never knew or can’t remember. Most people don’t really care about architecture anyway, but despite that, a few names get stuck in the cultural conversation. But what about one of Brooklyn’s most famous icons? What about the ball park with the name that can cause a native-born Brooklynite of a certain age to get teary and wax nostalgic? We know the name of the team, and the exploits of the players in that temple of baseball. Their names are whispered like they were saints in church.

But who was the architect of this sacred space? Who designed Ebbets Field, home of the Brooklyn Dodgers?

Clarence R. Van Buskirk, that’s who… well, maybe.

WHO?

Clarence R. Van Buskirk came from old New Amsterdam Dutch stock. His father was the Reverend Peter J. Van Buskirk, the long-time pastor of the Gravesend Reformed Church. Rev. Van Buskirk was the spiritual leader of one of Brooklyn’s oldest Dutch Reformed churches; one that was organized by early settlers in 1655. Young Van Buskirk was his parents’ elder son; they also had another son named William, who became a very successful lawyer. Clarence went to college at Columbia and became both an engineer and an architect.

He was well liked and in the social set in Brooklyn, so it came as no surprise that he got a job with the City of Brooklyn in 1895, as an Assistant Engineer in the City Works Department. A year later, he married Lillie Van Siclen, the daughter of another old Dutch Brooklyn family, whose family were members of his father’s church.

Van Buskirk settled into his new job. He was assigned to the Department of Highways, where he oversaw the work of his inspectors who looked at roads and bridges. His boss was Frank. J. Ulrich, the Superintendent of Highways for the Borough of Brooklyn. Ulrich was investigated for fraud in 1905 and ended up being indicted and arrested. Before he could be brought to trial, he resigned.

The new Brooklyn Borough President, Bird Sim Coler saw himself as the new sheriff in town, determined to make a name for himself as a fighter against corruption, and thereby propel himself into higher office. He began the investigation of Ulrich, ended his career, and thought he could bring down the entire department, including junior officials like Van Buskirk.

Because Van Buskirk was a civic employee, he was entitled to a hearing before any criminal charges could be made. As Borough President, Bird Coler chose to adjudicate that hearing. Clarence failed to show up. His lawyer issued a statement saying that if Coler wanted to officially accuse him of a crime, he needed to take it to the Grand Jury. His client was not going to allow himself to be called up on the carpet like an errant schoolboy.

Coler retaliated by firing Van Buskirk from his job. He promised that the Grand Jury and formal charges were next. But charges were never filed and the entire matter just disappeared, and was never spoken of again, not even by the press in the years that followed.

(1914 Brooklyn Eagle photo. They spelled his name wrong!)

After being fired, Clarence went into private practice, joining Alexander F. W. Leslie in the architectural practice of Van Buskirk & Leslie. They are on record for a couple of buildings in downtown Brooklyn. He also had a thriving business in Coney Island as an electrical engineer and was also involved with several South Brooklyn projects from his native Gravesend which put him in the same room with Bird Coler on several occasions. One wonders how this minister’s son reacted.

In early January 1912, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Charles Ebbets announced that he was going to build a brand-new baseball stadium in Brooklyn for the borough’s beloved Dodgers. He made the announcement at a sportswriter’s dinner at the Brooklyn Club on Pierrepont Street. The news was met with great applause and became the front-page story in all the Brooklyn papers the next day.

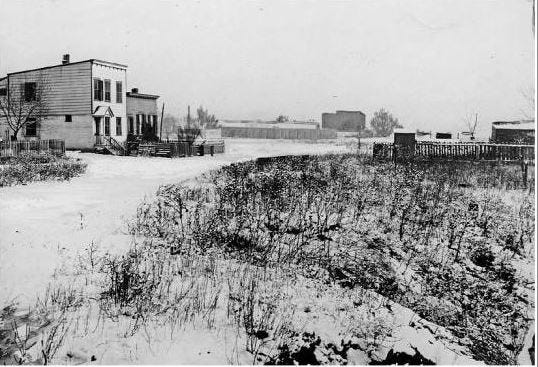

What was even a greater surprise was the news that the site of the stadium and its design had been in work for over a year and had somehow managed to remain top secret from everyone inside and outside of baseball and government. The new stadium was to be built in what is now Crown Heights South, in an underdeveloped section of Brooklyn at the edge of Flatbush known more for scrub fields, limited lower income housing and roaming goats.

(Area developed for Ebbets Field, Brooklyn Eagle, 1912)

As the plans became more formalized, a name appeared as the architect of this marvelous project. It was Clarence R. Van Buskirk. How Ebbets and Van Buskirk connected remains a mystery.

And what a design it was. Charles Ebbets was a smart man. He, Van Buskirk, and their unnamed steel construction engineer went on a long field trip a year before the announcement, gathering information from other parks on what worked, didn’t work, and what could be improved upon. They visited parks in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago, St. Louis, and ended at the Polo Grounds in Manhattan, the original home of the NY Giants.

The team took something away from each ballpark. Some of it was obvious and important, like the size and placement of exits and entrances. They also noted the little things, like armrests on stadium seating (bad), and made copious notes for Ebbets Field. At the time they went on their trip, no one except Ebbets knew that this would be for a new stadium in a new location. Even Van Buskirk was under the impression that Ebbets was going to remake the team’s old home turf, Washington Field, on the Gowanus/Park Slope border, not build a new stadium in another part of town.

Everyone was sworn to secrecy on the project. Clarence always had the plans on his person. Whenever anyone came to his office or to Ebbet’s office, Clarence whisked the plans away, and carried them around. No one was going to find out about this until Charles Ebbets made his announcement. The pressure and secrecy was all a bit much for Clarence, who had to take to his bed when it was over, but Charlie Ebbets was elated. His stadium would have the best of the other major stadiums and would be better than all of them.

(One of the exterior blueprints, now in the collection of Brooklyn College)

As can be imagined, when he did make the announcement, Brooklyn was elated and excited. The Brooklyn newspapers printed pages full of stats about the capacity, the square footage, as well as how many feet the outfield would have, how many seats were in the stadium, how many fans could squeeze in, and other building details. One modern innovation – the new stadium would be built with dedicated parking garages nearby. They realized that the car was as important to attending fans as the nearby public transportation. The location of Ebbets Field would greatly aid the growing popularity of Automobile Row, already established on nearby Bedford Avenue.

The stadium was built to hold 30,000 people. Opening day was scheduled for Flag Day, July 14th, 1912. If the stadium was delayed, August 12th was the back-up date. The opening date, of course, came and went, as did the back-up date. This is New York City, and nothing has ever been built on time here.

The ground breaking ceremony took place on March 4, 1912. The cornerstone wasn’t laid until July 6, 1912. A Brooklyn Eagle article said that Clarence was there every day, usually late into the night. According to the paper, “The park as it stands today is the best tribute to Mr. Van Buskirk’s tireless endeavor. He stuck on the job as if he were building the place for his very own and stuck around so much that when he went home, he felt as if he were visiting and reached for a card to hand to whoever opened the door for him.”

His wife Lillian thought he was a visitor to her house, as well. She was not pleased.

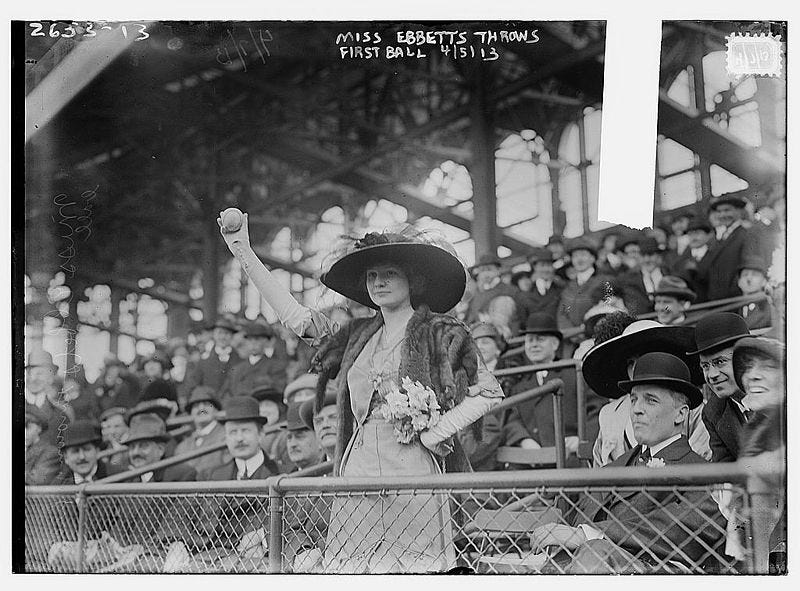

(Ebbet’s daughter throws out the first ball, opening day. Photo: Wikipedia)

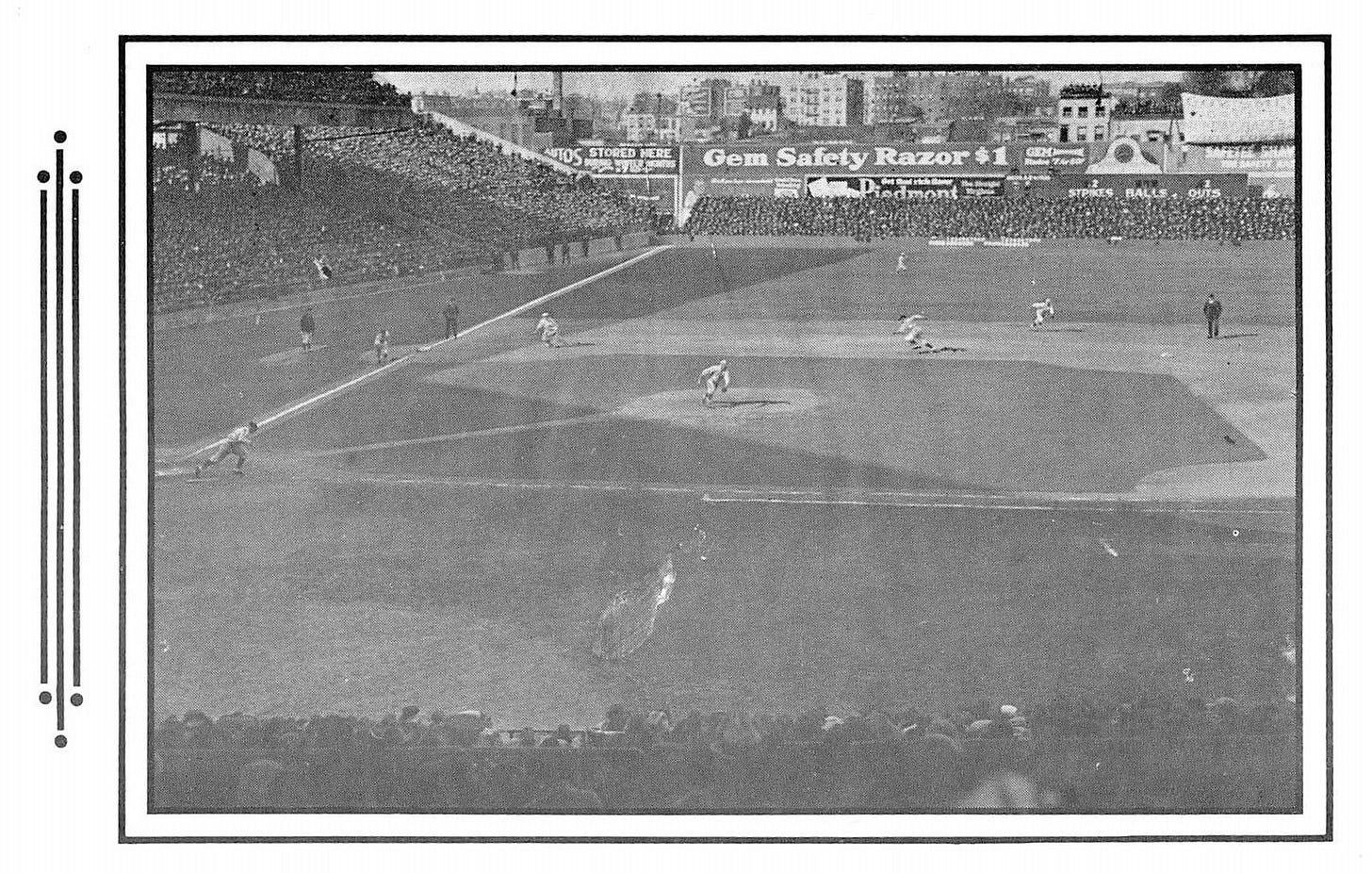

Ebbetts Field, home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, opened almost a year later with an exhibition game between the Dodgers and the Yankees, held on April 5, 1913. A few days later on April 9, the Dodgers played their first league game here against the Philadelphia Phillies.

Although a great deal of planning went into Ebbets Field, they forgot a few things. They had no press box. It took until 1929 for that to happen. They had to reconfigure and add onto the seating. They also had to add a larger scoreboard, which didn’t happen until the 1940s. But, hey, it opened with what they had, and most people were happy. Ebbets Field entered into the lexicon of legendary early 20th century ballparks.

Van Buskirk was happy, his reputation was soaring. He placed ads in the papers next to articles about the stadium, touting his role as architect. But as 1913 was progressing, the stadium would be the only bright light in Clarence’s life.

In January of 1913, Lillian Van Buskirk received a bill from a furniture store. The bill itemized the purchases by her husband and listed the delivery address as a building in Sunset Park. The furniture was for a Mrs. Van Buskirk. She had suspicions about Clarence’s activities since 1908, so she took a trip over to Sunset Park and spoke to the building owner. She showed him a photograph of her husband, and the owner verified that that man and a woman had rented an apartment from him and had been introduced as Mr. and Mrs. Van Buskirk. They also had another older woman living there, and she had been introduced as “Mrs. Van Buskirk’s mother.”

The real Mrs. Van Buskirk called her lawyer and filed for separation and divorce. Lillian and their ten-year-old son Bertram went to live with her parents. It was February. In March, Clarence’s father, the Reverend Peter Van Buskirk died. The stadium opened in April. Soon afterwards, Clarence’s business partner, Alexander Leslie broke up the partnership, and filed suit against Van Buskirk. Leslie alleged that he, not Clarence, had been the primary designer of the stadium.

Leslie charged Van Buskirk with fraud and said that Clarence and Charlie Ebbets had a “secret agreement” between themselves, which involved Clarence being paid on top of the agreement the firm had struck as a whole. Leslie’s attorneys also alleged that Clarence had been dishonest with Leslie from the start of their partnership. Leslie charged that Clarence had totally misrepresented himself and had never turned over their financial books to him, as Leslie had repeatedly asked him to.

He also brought up the unpleasantness at the Highway Department, with the allegations that Van Buskirk had been fired because of his involvement in payoffs and preferential treatment. And to top it off, Leslie alluded to Van Buskirk’s growing marital problems, all contributing to his dishonesty, and general untrustworthiness. It didn’t look good for Clarence at all. It was all circumstantial and gossip, but it was damaging gossip.

But somehow, he managed to get through 1913 unscathed, riding on the coattails of Ebbets Field. But 1914 was not a good year. Not a good year at all.

On January 12, 1914, Alexander Leslie died at the relatively young age of 58. But unfortunately for Clarence, Leslie’s lawyer and widow intended to continue the suit. Mrs. Leslie said that her husband had papers that proved that he, not Clarence Van Buskirk, had designed Ebbets Field. On the marital front, in May, a judge ordered Van Buskirk to pay his own wife $15 a week in alimony, and a $30 fee for her lawyer. This decision was made after the revelation of the second “wife” and her apartment became an official part of the divorce proceeding.

Clarence told the judge he couldn’t do it – he was flat broke. He was living at the Crescent Club in Brooklyn Heights, the upscale club was almost a dormitory for separated husbands. The judge was not sympathetic. By July, Clarence was back in court. He had failed to make his alimony payments for two weeks. The judge declared him in contempt of court, and gave him two weeks to pay up, or he’d be going to jail. Lillian’s lawyers advised they jail him now, as he was going to skip town. The judge was a Dodgers fan, so he gave him the two weeks.

Then Clarence completely lost his mind.

(1896 illustration of the Bedford Rest, from the Brooklyn Eagle)

On August 11, Clarence checked into the Bedford Rest, a hotel and restaurant on Eastern Parkway at Bedford Avenue. The next day, he was going to have to turn himself into the court, as he had not paid his wife her alimony as ordered and was going to end up in jail. He would be incarcerated with other deadbeat husbands in a section of the jail called the “Alimony Club.” He spent his last night of freedom at the hotel, a place he had been many times before.

The next morning, before the establishment opened, the owner saw him hanging out by the entrance to the upstairs storeroom. He watched Clarence slip through the open entrance and go upstairs with his suitcase. When he came out, he shut the door, looked around, and walked away. The owner had a policeman stop him. Inside the suitcase were 14 boxes of “2 for a quarter” cigars. Van Buskirk was arrested.

Standing before a judge, Clarence was a mess. He told the judge that he had been drinking and must have lost his mind. He explained that he knew he was going to the “Alimony Club” and suddenly thought it would be a splendid idea to have some cigars there to share with his fellows and pass out to the guards for favors. He knew his key fit the upstairs storeroom door, and he just helped himself.

He went on to explain that his wife was bleeding him dry, his business had “gone to smash,” and he didn’t know what to do. He didn’t know why he did it. The proprietor of the Bedford Rest wanted to press charges, and Clarence found himself at Raymond Street after all, and not in the Alimony Club part of the jail, either.

Clarence got out on bail. A few days later, his lawyer tried to get the charges reduced. He argued that since the door leading to the storeroom had been open, Clarence had not broken in, and should not be charged for the more serious crime. The judge grudgingly agreed he had a point. He would rule on the decision. The charge was reduced to petty larceny, and the proprietor of the Bedford Rest declined to press charges further. Clarence Van Buskirk was free to go, the case was dismissed.

On September 30, 1914, Lillian Van Buskirk received her final divorce decree from the courts. The judge upheld the $15 week alimony and added an additional $5 a week for child support. Clarence wasn’t there, his hard-working lawyer represented him at the proceedings. We’ll never know if he paid up, or simply left.

In 1916, Clarence Van Buskirk’s name came up in an ad for Germany’s Daimler Automobile Company. Clarence was being credited as one of the designers of Daimler’s “Mercedes” brand automobiles. Was Clarence in Germany? During World War I? No other details were mentioned, or available. But a Clarence R. Van Buskirk did arrive back in NYC in 1935 on a ship sailing from Paris. Hmmmm.

Years later, in 1940, a Clarence Randall Van Buskirk was living alone in Pontiac, Michigan. The census lists him as an architect. He had been at that address since 1935. He was one of two lodgers in a private house. He was 57 years old. Was that him? The census records show several people with that name in various parts of the country over the years. According to public records, that Clarence died three years later, on January 9, 1943, in Oakland, Michigan.

The Dodgers beat the hated Yankees at Yankee Stadium in the seventh and last game of the World Series in 1955. Then Brooklyn lost the Dodgers to Los Angeles in 1957. In 1960, Ebbets Field was torn down for housing. The Ebbets Field Houses still stand on the site of the stadium. A few original garage buildings remain. They won’t be there much longer, they stand on valuable land wanted for apartment buildings. Soon there will only be photographs of Ebbets Field and the buildings the ballpark made possible.

Did Clarence Van Buskirk design Ebbets Field, or did Alexander Leslie? No one remembers either one of them, but history records Van Buskirk as the official architect. Although his life was a rollercoaster of talent and very bad decisions, he made the history books after all.

I have probably said this before in comments on your articles. I generally don't know about many of the different people, places, or buildings you write about. But once I start to read one of your posts, the amount of research you do almost makes the stories come to life for me, like watching a movie.

What interesting story!!! I’ve always wanted to know the history of Ebbets Field. I really enjoyed it!

Tom