The Devil’s Weed

Cigars dominated the smoking habits of the 19th century. It got ugly in many ways.

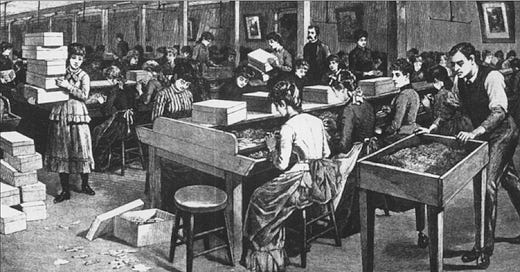

(Cigar factory workers, 1887, as portrayed in Harper’s Magazine)

When Christopher Columbus and his men saw the Taino people of the Caribbean rolling large dried leaves, lighting them and inhaling the smoke, it took them no time to try it too. The global love affair with tobacco had its humble and disastrous beginnings there, back in 1492. The Spanish introduced it to Europe, and by the 1600s, everyone was hooked. The British were buying so much Spanish tobacco that they almost bankrupted the country, creating a coin shortage that took an Act of Parliament to halt.

All the Europeans who established colonies in the New World counted tobacco as one of the most important trade commodities. The colony at Jamestown Virginia was established so that they could grow and export tobacco back to England and break the grip of Spanish tobacco.

Cigars were inevitable. The word comes from the Spanish “cigarro”, which came from the Mayan word “sicar,” which means “to smoke rolled tobacco leaves,” sensibly enough. By the 1700s, the word was in use in English. By the beginning of the 18th century, everyone smoked, except the Puritans, and even they would sneak a pipe in occasionally where no one could find them.

Men have always been the biggest smokers, but back then, women smoked pipes and cigars, too, and even children were allowed to smoke. Snuff was also popular, and all tobacco products were big business for the colonies, and later the fledgling United States.

Quality was always an issue, and tobacco leaves were inspected in all states before being shipped overseas. Some of the most powerful tobacco came from New England, believe it or not. Cigar tobacco was the best tobacco, leaving lesser grades for pipes and snuff, and later, cigarettes. Standards and rules were set up for the growing, harvesting, sorting and drying of tobacco leaves, for both domestic and foreign sale.

So, what is a modern cigar, anyway? According to Wiki, “Tobacco leaves are harvested and aged using a process that combines use of heat and shade to reduce sugar and water content without causing the large leaves to rot. This first part of the process, called curing, takes between 25 and 45 days and varies substantially based upon climatic conditions as well as the construction of sheds or barns used to store harvested tobacco. The curing process is manipulated based upon the type of tobacco, and the desired color of the leaf.

The second part of the process, called fermentation, is carried out under conditions designed to help the leaf dry slowly. Temperature and humidity are controlled to ensure that the leaf continues to ferment, without rotting or disintegrating. This is where the flavor, burning, and aroma characteristics are primarily brought out in the leaf.”

Once the leaves have aged, they are sorted, and the better leaves become the wrappers, while the lesser become the fill. A good cigar is hand rolled, with the leaves moistened for softness and ease of use. An experienced cigar roller can make hundreds of cigars a day, using a special curved knife called a “chaveta” to manipulate the tobacco, and form and shape the wrapper. As most people know, there is a long Cuban tradition of cigar making, but in the 19th century in New York, the tobacco rollers were from many different countries and nationalities.

In researching this story, what surprised me most was that almost every city and town in the country seemed to have had a cigar factory, usually several. Larger metropolitan areas could have hundreds. One did not need a large factory building to be a cigar roller. You only needed the tobacco leaves, which could be grown relatively locally, some tools and a table. Consequently, this was soon an industry begging to be abused by the greedy and embraced by the desperate.

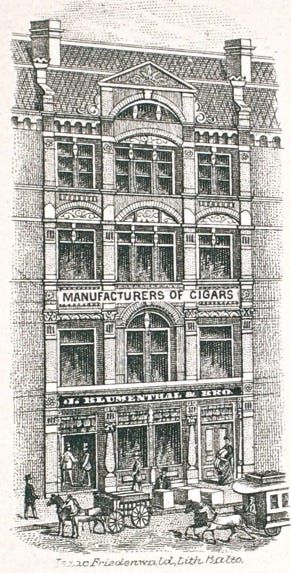

By 1860, the American cigar industry was growing rapidly. A very conservative estimate at the time reported that there were over 1,478 cigar manufacturers in the United States, with 8,000 people employed in it, men, women and children. Other estimates say that the number of manufacturers was close to 5,000. The government, both local and Federal, had finally figured out how to tax the lucrative industry. All cigars had to be packed in boxes that had only a one-time use. They were affixed with tax stamps signifying that the tax had been paid on that particular box of cigars.

There were rules regarding the size of the boxes, the number of cigars in those boxes, as well as a grading system for the quality of the cigars, and more. Cigar boxes were wood, metal, and later, cardboard. The familiar cigar ring was invented as advertising during the 1860s, as once a wrapper was off, no one could identify whose cigar it was. The paper ring assured bragging rights. The tax laws regarding cigars were complicated and confusing, even to the tax collectors. It would take a decade to simplify them. Meanwhile, the makers of cigars organized, founding Cigar Maker’s National Union of the United States in 1864, one of the first trade unions. They would need it.

Pennsylvania, which grew a lot of tobacco, was the largest cigar manufacturing state in the country. New York state was the second largest. 41% of their close to 5,000 factories were in Manhattan alone. Brooklyn had over 900 factories, with only one large factory: Jensen & Wallach at 24 Adams St. and only 30 medium sized factories. All the rest were small family run, or single person businesses. Just as a comparison, upstate Oneonta had 6 factories, Troy had 56, and Buffalo had 125. Albany had 140.

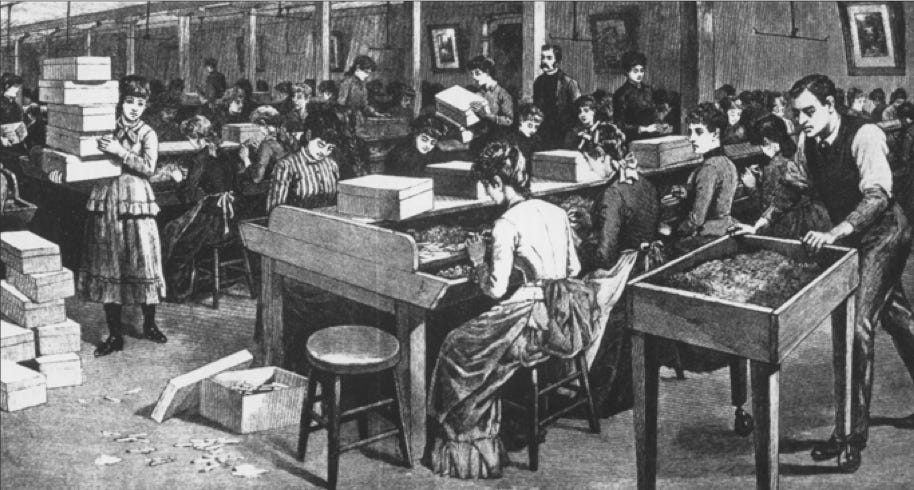

(Workers in a cigar factory, late 19th century. Photo: cigarhistory.info)

The larger factories were unionized by the 1880s, and many of the workers were Spanish-speaking, mostly from Cuba and Spain. Many of the higher end cigars and the shops that made them were owned and run by Cubans or Spaniards. Then, as today, the Cubans were the craftmasters. The workers there were higher paid, even though their output was lower than those made by other factories. They also used Cuban and Sumatran tobaccos, a much finer grade of tobacco than the home-grown American variety.

The other factories were generally staffed by people from Germany and Bohemia, which today is the Czech Republic. A member of the Cigarmaker’s Union had to have a three-year apprenticeship before being eligible for journeyman status, and full membership in the union. But although thousands of factory workers were women, the union did not admit them, it was for men only. Female cigar workers made the same product as their male counterparts, but were only paid half of what the men received.

The larger factories employed a lot of women, especially when the new cigar molds and cigar making machinery were introduced into the industry. The machines took quickness and dexterity, and the ideal woman operator was between 16 and 25 years of age. But some of the smaller factories did not hire women at all because they would have been forced by law to have a separate bathroom for them.

Medium sized factories employed from 10 to 99 rollers. They were usually in larger towns and cities and were housed in multi-storied buildings where the different operations were performed on different floors. Tobacco storage, sweating and blending took place on the first floor; the cigars were manufactured on the second floor, and packed and shipped from the top floor. If the factory was in a good commercial area, the first floor would also be used as a retail shop. Most of the product from these factories was wholesaled out. The railroad insured deliveries across the country and to more isolated areas. Most of the actual rollers in these factories were women.

The large factories had 100 or more rollers. They could make 25,000 cigars a day. In 1885, there were 24 huge factories in the US that had 500 or more rollers, three had 1,000. They could manufacture a quarter million cigars a day, or 50 million a year. They made their own brands, which sold to wholesalers, jobbers and retail stores or they could make private label cigars to retailers and distributers who wanted their own name brands. The demand for cigars was so great that all these factories, large and small could make money. All this production needed a lot of workers, and although by this time only men smoked cigars, at least in public, women and children played important roles in their manufacture.

Cigar rolling took agile fingers. Ideally, a good cigar roller started as a child, with the nimblest fingers of all. Teenage girls were also desirable, as they made the best workers in the larger factories. But as production increased, quality decreased, so you basically had two completely different industries. The famous Cuban cigar makers were generally men, and they trained since boyhood in their crafts.

They made a higher-grade product, all hand rolled with superior tobacco leaf, hand cut to use the best of the leaf in the center pack, as well as in the leaves that rolled around them. They knew how to shape the cigars, with larger centers, tapering down to more slender ends, and did so with experience. They knew how much moisture was needed to make the tobacco adhere to itself. These were the highest paid craftsmen.

Below them were rollers of lessening ability, from different nationalities, and on the bottom were the factory workers who churned out thousands of cheap cigars made in molds. Instead of gently shaping the cigar with carefully cut leaves, these were made by packing tobacco into a mold and quickly wrapping it. The factory owners did not want their rollers lingering over a perfect product, they wanted volume. This piecework could also easily be taught to new workers who did not have any experience in rolling at all, and in short order, they could be producing product by the hundreds a day. This mass production produced all kinds of cheap product, and it also gave way to the worst in industrial abuse of workers, especially women and children. This came in the form of the “cigar tenements.”

In addition to all the legit factories, there were thousands of illegal tenement factories. Here entire families worked to produce cigars, living in the worst conditions of poverty themselves while making an organic food product to be sold on the open market; one you put your lips on and drew into your body. Think of the health hazard possibilities. Local officials did, and finally banned the tenement cigar factories. So they all up and moved to Brooklyn, which was still an independent city.

The very small cigar factories, the “Mom and Pops,” were disdainfully called “buckeyes” and “chinchallas” (cockroaches) by the larger factories. They employed less than ten cigar rollers, and many were family operations that had only two or three rollers. These operations comprised 70% of the number of factories in the statistics. They were run in sheds, attics, storefronts, private homes and tenements. The goods were sold to wholesalers who distributed them under many brand names, and the quality of the product varied greatly.

In New York City, Brooklyn, and other cities, the cigar tenements were an urban form of sharecropping. The factory owner owned the buildings, which were full of families who were slaves to the cigar industry. These were mostly new immigrants to the United States; Poles and Bohemians primarily, who had come here with nothing, and were uneducated and dirt-poor peasants. Unscrupulous cigar manufacturers hired these families, put them up in their buildings, and had them making cigars at home. The entire family worked to produce cigars in their small flats, competing with cockroaches, rats and mice for space in the rooms. The children remained unschooled, and no one learned English, or any other skills, helping to further guarantee that they remained in their state.

The workers worked day and night to meet the quotas, while continuing to live in the worst conditions imaginable. We’ve all read about and have seen photographs of the piecework garment workers of the Lower East Side, and as horrible as their conditions were, the cigar makers were worse. Social reformers referred to these factories as “dens,” their conditions especially foul and dangerous for the thousands of children who worked in them.

The children who worked alongside men and women were generally from 9 to 14 years old. Some were as young as 5. There were some child labor laws in place in the 1880s, and they were supposed to ensure that no children under 13 were to be employed in factories, but inspectors were not required to be in places with less than five employees, so there was no danger of being closed by inspectors who may not have been able to find these places in the first place. Besides, these “factories” were in their homes.

Most of these workplaces had little or no ventilation, so that tobacco dust was everywhere, on everyone and everything, and being breathed in regularly. Children were suffering from lung diseases like consumption right and left. They were also barely eating, taking only the time to wolf down a “poor man’s sandwich” which was a bit of bread between two pieces of bread. Children and adults lived surrounded by tobacco scraps on the floor, which found their way under beds and tables, where they rotted, smelled, and drew vermin and insects. Personal sanitation was lax, poverty and squalor pervasive, and all to produce enough cigars as to pay the rent, to stay in the tenement, which required you make cigars. It was a vicious circle.

(Tenement cigar “factories,” illustration. Via cigarhistory.info)

On top of the horrible conditions for those producing the cigars, the product would have churned the stomach of those who smoked them, had anyone cared to find out. The tobacco was inferior anyway but was stored and moistened for use in filthy conditions, made by people who were not themselves clean and not especially healthy either. Consumptive people were coughing and expectorating all over the tobacco, while using leaves that were being chewed by rats, and harboring roaches. Sometimes saliva was used to moisten the leaves and finish off the cigar, and the same hands that changed diapers in a corner were then wrapping cigars moments later.

The cigar unions were furious at this activity. A moral sense of horror that people were living that way was mixed with financial outrage, because the tenement factories were producing an inferior product that was cutting into their bottom line. Many of the tenement workers were also brought into the larger factories as scabs when the unions went on strike. Factory owners were also complaining that the tenement cigars were going out into the market as bootleg product, without taxation. The government, both federal and local, was making a tidy penny in the taxation of cigars, but tenement cigars often were sold illegally.

(Female cigar factory workers. Photo: cigarhistory.info)

By the 1880s, many changes had come to the cigar industry. Tobacco workers’ unions forced manufacturers to raise wages and slightly improve working conditions. But the unions only represented the men, not the women who worked in the large factories. Women were prized in the cigar rolling business for their smaller hands, manual dexterity and their ability to pack and roll a cigar with more ease than men. But they were still exploited for being women. They were expected to have the same quotas as men but were paid only a third of the wage. Where a man might make $10 a week, a woman doing the same job would make $7.

Consequently, many large cigar factories employed a lot of women and girls between 12 and 16 as rollers. This was the highest paid, most skilled job, and employing women kept costs down. Men rolled as well, but also did other jobs, such as hauling, grading and chopping the tobacco, as well as boxing, packing and shipping. Children were often employed to strip the leaves, taking the hard stem out of the middle. Then the tobacco had to be soaked just enough to be malleable, but not rot. It wasn’t easy.

Social reformers in Victorian society took up the factory worker’s cause, seeking to pass laws to force factory owners to improve conditions and wages, as well as improve the lives of working children. Most reformers wanted to banish children from the workplace all together, but that would not happen for some time. They faced an uphill battle in a society that felt that each man’s business was his own and shouldn’t be interfered with. That society also didn’t much care about the working conditions of the poor. But gradually laws were passed, forcing improvements in factories in general, including one that forbade the employment of children under twelve.

The tobacco industry was a cash cow for the government, in terms of taxes. In 1880, tobacco tax accounted for one-third of Federal revenue. 50% of the collections came from smoking and chewing tobacco, 40% from cigars and cheroots, 8% from snuff and less than 2% from cigarettes. By this time, there were hundreds of brands of cigars, ranging from cheap to high grade Cubans. The latter were even then in a class by themselves, and rare, due to growing problems in Cuba, and later, war. The familiar cardboard cigar boxes, and metal tins were part of a large industry of related products that were also making a lot of money for the industry.

Cigar boxes were a great way to pack, store and market cigars, but they were really developed so that the tax stamps could be easily affixed to them. These paper stamps sealed the boxes, and also indicated that all of the federal, state and local taxes had been paid. Cigar boxes and tins were also among the first successful means of mass marketing advertising, which was also becoming a huge industry. Even the classic American cigar store Indian was a part of that marketing. They were made by cigar manufacturers to advertise to those who couldn’t read, or speak English, that cigars were sold at the stores they were in front of.

In 1903, the New York Herald published a long article hailing the cigar machine. It was in their financial section, not on the regular news or technology pages. This machine, the article gushed, would revolutionize the cigar industry. The Carpenter Cigar Machine could cut factory costs in half. Operated by a girl, “the Carpenter Cigar Machine will make as many cigars in a day as six expert workmen can roll by hand. The average output in the modern cigar factory is 300 cigars per day per man. The Carpenter machine will make 2,000 cigars per day.” The article was an ad to buy stock in the company. It warned in capital letters that, “The cigar manufacturer of the future MUST USE OUR MACHINE OR GO OUT OF BUSINESS!”

Although this was a lot of hype, it signaled a large change in the business. It effectively put the tenement cigar factories out of business. Cigar manufacturing in larger factories became part of the larger manufacture of cut leaf tobacco and cigarette manufacturing facilities. One by one, the cigar factories in towns and cities across the country closed. The much smaller and cheaper tobacco product, the cigarette surpassed the cigar as the tobacco product of choice. Cigarette production boomed when machines that could roll them took over the industry. The newly popular cigarettes were marketed, brands are targeted to women and young smokers, and the tobacco industry totally changed direction.

The industry centralized behind the large tobacco companies. By World War II, the cigar industry was made up of only several large tobacco conglomerates, and imports from Cuba and a few other places. A few specialized tobacco stores still made their own, but nothing like in the past. Florida, with its larger Cuban and Dominican population replaced New York as a cigar manufacturing center. The government, which had always made a great deal of money from taxing tobacco, found an even larger cash cow in cigarettes. Cigars lost popularity and became a specialized, but much smaller niche market.

The age of the cigar had passed. The rest of the 20th century belonged to cigarettes.

(Tomorrow - The Draft Riots of 1863 tore NYC apart, as black people in NY were among the targets of rioters protesting the draft during the Civil War. But even before that, the idea that black Americans were taking white jobs resonated in two cigar factories in Brooklyn. This little known story is on deck for tomorrow.)

Regardless of the subject of your writing, the amount of research always amazes me. Hope you take a little time for yourself occasionally.