“The Great Mistake,” The Story of the Creation of New York City

Brooklyn never really got over it.

(Pedestrians crossing the Brooklyn Bridge, 1905)

With Brooklyn’s status as the newest “Hippest Place on Earth”, comes some nostalgic feelings about the “Great Mistake”, the consolidation of New York City. On that fateful day, January 1, 1898, Brooklyn, the city, disappeared, and Brooklyn, the “outer borough”, was born. (As were the Bronx, Queens and Staten Island.) The decision to join all the counties surrounding Manhattan into one central city was not made easily, quickly, or lightly. Politicians, businessmen, city fathers and ordinary citizens argued and lobbied for, or against this for almost twenty years. Involved was a tremendous amount of money and power, business interests, tax revenues, city bureaucracies, and social issues and civic identity.

For some people, it was inevitable and progressive. For others, it was the Death of Brooklyn. The bill that created the municipality of New York City was signed into law on May 1, 1897, but the talking and the negotiating had been going on for years beforehand. As early as 1873, the leading citizens and politicians of both New York and Brooklyn began talking about joining the two cities. The union was always presented as the annexation of Brooklyn by Manhattan, not a true merger of equals.

By the 1890’s, the commission overseeing this matter, the Greater New York Commission, had concluded that just annexing Brooklyn would do little for New York City. Brooklyn had its own debt and financial obligations, and the joining of the two cities would skew towards advantage: Brooklyn. It would get more tax dollars and Brooklyn property values would rise. They needed to add more boroughs to keep Brooklyn in check. Simply joining the two cities would not have the tax revenue, or the overall growth needed to keep New York the first city in the nation.

That title would be taken over by Chicago, which was growing far faster than New York, threatening to become America’s largest and most prosperous city. For Greater New York to generate the tax revenues needed for continued growth, it needed to think bigger. It needed to add the Bronx, Richmond and Queens counties, so the idea of a truly Greater New York City was now in the hands of legislative committees.

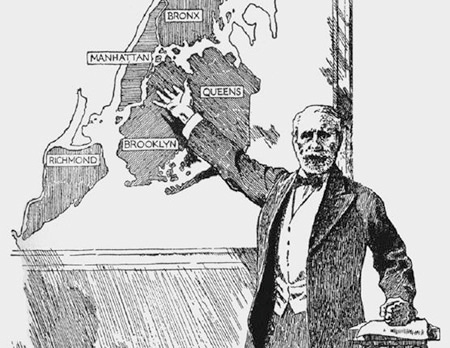

(Andrew Haswell Green explaining the new city. Richmond is Staten Island for those not familiar with the city)

The chief mover of the Consolidation movement was Andrew Haswell Green, a Manhattan lawyer, city planner, and visionary. He was born in 1820 in Massachusetts, studied law under the tutelage of Samuel Tilden, and was a member, then president of the NYC Board of Education. Through the course of his career prior to consolidation, his name was associated with the creation of Central Park and the creation of the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Natural History. It was also his idea to join the endowment of his mentor, Samuel Tilden, with the Astor and Lenox funds, to facilitate the creation of the New York Public Library.

Green was appointed by the State to be the head of the consolidation committee. He wanted to join New York’s greatest treasure, its harbors, under one municipal jurisdiction, free of the petty bureaucracy that was hindering the growth of the city. He wanted to develop transportation lines, bridges and new port facilities, but the fractured power of different municipal governments, along with their graft, petty politics and jealousies was helping to keep progress away from New York. The main opposition came from Brooklyn, where Green’s efforts were derided as “Andy Green’s hobby”.

The whole of the 19th century saw Brooklyn grow from six villages to become the third largest city in the nation. Brooklyn had important industries, ports, centers of business, its own civic center, cultural institutions, and diverse neighborhoods. It had its own transportation centers, rail and streetcar lines and roads.

Brooklyn had its own independent parks, police, corrections and fire departments, water and gas companies, and later, telephone and electric companies, as well as a separate, and very progressive public school system. It had its own government, courts, and newspapers. Had Brooklyn been located anywhere else, it would still be an independent and successful city. But it was directly across the river from Manhattan.

By 1883, it was a well-known fact that the economies of the two cities were intrinsically linked. It started with the waterfronts and rivers, and Manhattan always had the advantage. From the very beginning, it grabbed control of the bays, the East River, the Hudson and Harlem Rivers. When ferries began crossing back and forth to Brooklyn, Staten Island, New Jersey, the Bronx and Queens, they were all under a Manhattan-centric schedule and control.

Water traffic was the lifeline of the city of New York, with goods and services coming and going, and people commuting to the financial and business center of Lower Manhattan. With everything and everyone coming to Manhattan, it was inevitable that a greater city would center in Manhattan.

Brooklyn, of course, was growing up to be a major city, too. By the 1850’s, the state had combined Manhattan and Brooklyn’s police, fire and health boards into a joint metropolitan board, still separate in jurisdictions, headquarters, and officials, but sharing resources, information, and operating practices.

By the 1870’s, talk of a Greater New York City began in earnest, and in 1874, Manhattan annexed part of the Bronx, and began the process that would create the Bronx as a part of New York City, separating it from Westchester County. They annexed the even more territory in 1895, setting up the borough as we know it today. Brooklyn, in the meantime, began to annex all its towns into one united city.

Many civic leaders and businessmen on both sides of the river knew that what was good for one city had a positive effect on the other. Those who were for consolidation spoke lavishly of the profits that would be made, especially in Brooklyn, as space-starved Manhattanites swarmed to Brooklyn in search of homes, and businesses flowed across the bridge in search of room for factories and warehouses.

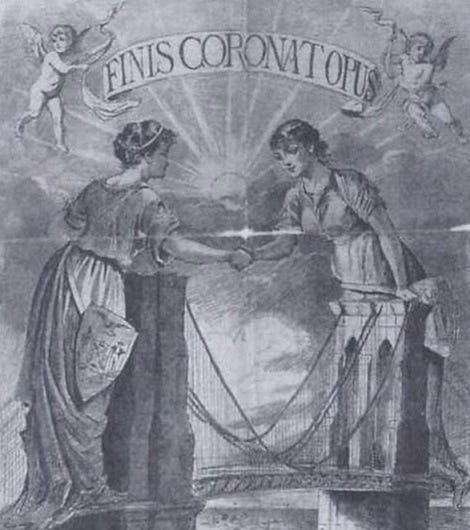

(The meeting of two gracious ladies: Manhattan and Brooklyn, 1898 illustration)

To not sound quite so mercenary, and smooth out the crass commercialism, these same people also spoke of how the well-heeled ladies of Brooklyn would be able to claim they were from New York City, when they travelled abroad, or around the nation – a bragging point as impressive as being from London, or Paris. Speaking of which, these consolidation boosters noted, a greater New York City would then have the population, physical size, and municipal power, as great, or greater than London or Paris, putting us on a par with Europe’s great cities, something that Americans have long been obsessed with.

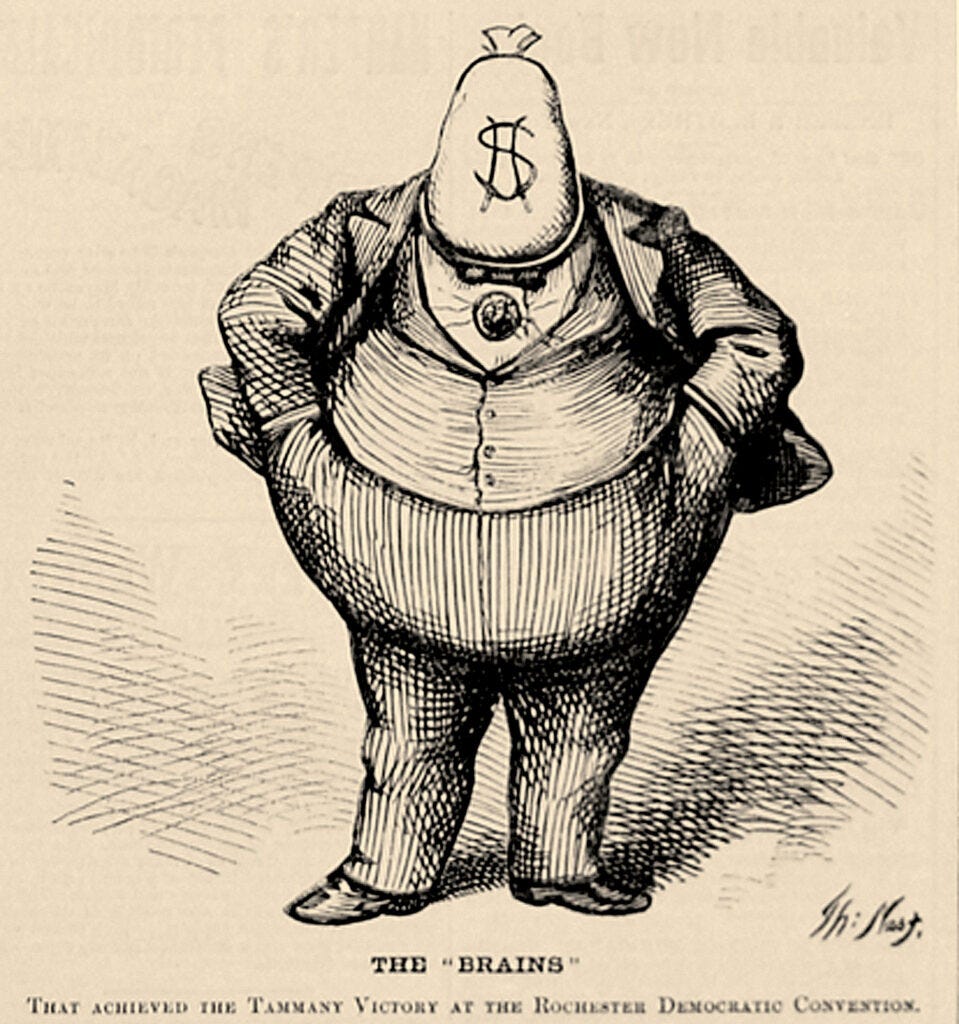

For many of Brooklyn’s elite, consolidation was a matter of Brooklyn getting taxed for Manhattan’s problems. They saw their taxes rising. They also saw Brooklyn losing its identity and civic pride, and identity many had worked hard to create. And they were very afraid of Manhattan’s Tammany Hall.

(One of many cartoons by Thomas Nast, depicting Tammany Hall’s Boss Tweed)

One of the most powerful political machines to ever run a city ran Manhattan from 1854 to 1932. Tammany Hall was most famously led by “Boss” Tweed from 1858 to 1872. After his arrest and subsequent death, power passed from leader to leader, but whether the mayor of the city was a Democrat, or an occasional Republican, the real power of the Tammany machine ran New York. It was notoriously corrupt, using New York’s rising immigrant population, especially the Irish, to further its goals.

The Republican Party, which had run Brooklyn for as long as Tammany ran Manhattan, was very powerful, as well. Many Republicans were personally against consolidation, and the loss of their own power. They rallied many to their cause by painting Manhattan as the city of Democratic graft and corruption.

But there was certainly dissention in their ranks, as many Republican businessmen could see the advantage and opportunities offered by joining New York City. Personal interests won out over political loyalty, and by 1895, Manhattan and Brooklyn Republicans had organized around Republican Boss Thomas Platt, who came out for consolidation.

(Chicago World’s Exhibition, the 1892 World’s Fair. Photo: Library of Congress)

And then there was Chicago. The Windy City loomed large over the talk of consolidation because Chicago was on the rise. Chicago, with its railroads, and Great Lakes traffic, was the premiere city of the Midwest, as much a hub for business and industry as New York, and was more and more, a destination for new immigrants from Europe, making their population rise, as well as their potential workforce.

Chicago beat NYC to host the 1892 World’s Fair. Chicago was a threat to New York’s dominance as premiere city in the United States. If ever there was a reason, outside of money and power, which the average person had no say in, for a consolidated New York, one need only look west. It was time to step up.

Andrew Green drew up the lines for consolidation, choosing what are now the five boroughs because of one thing: they brought together all the major port facilities in the metropolitan area. Brooklyn and Manhattan are obvious, and the Bronx was basically a part of Manhattan, for the most part. Long Island City, Queens was its own independent city, as well, and its shoreline was important to the plan, as was Queen’s Jamaica Bay and the waterfront and bays of Staten Island. It was all about access to the waterfronts and ports.

In 1894, a non-binding referendum was passed, with a majority voting for consolidation, even in Brooklyn, where it passed by only 300 votes. This had two opposing results. The pro-consolidation forces considered the vote a victory, and thought consolidation was now a done deal. They were wrong. The anti-consolidation opposition kicked into high gear, ratcheting up the anti-consolidation sentiment to the point that by 1895, they were able to block any further legislation.

Andrew Green was road blocked. It would take Republican Thomas Platt to wrest the movement away from the idealist Green. He got down and dirty, and called in his political favors and muscle, and the measure was pushed through the legislature in 1896. The charter was passed in 1897, and on January 1, 1898, Greater New York City was born.

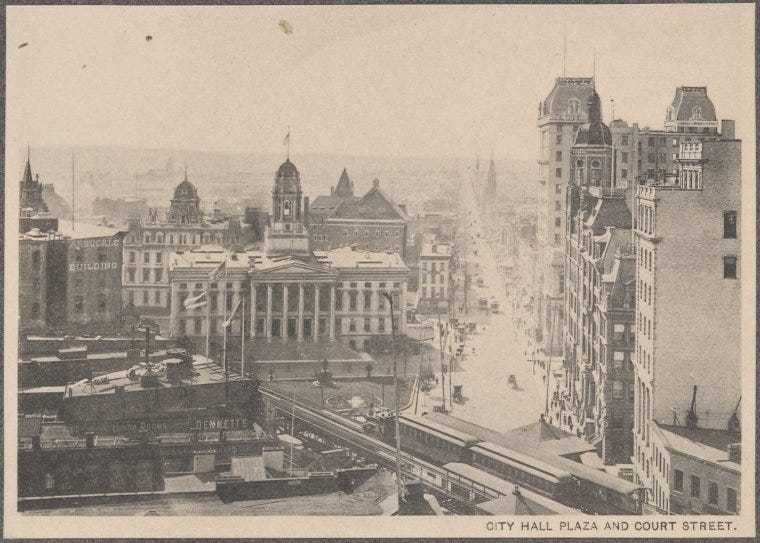

(Brooklyn’s City (now Borough) Hall Plaza, with el train running past it. Late 19th century)

What must have it been like to wake up in Brooklyn, on January 1, 1898, and realize that you were not in an independent city; you were now a part of Greater New York City? To be no longer the captain of your own team, but now only one of the players on someone else’s team. I would imagine for most people, especially the average working man in New York, the consolidation meant nothing, and it was just another New Year’s Day. Some Brooklynites embraced the change, eager to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the new rules. And some people, who were dead set against the whole thing, raged, mourned, and took pen in hand to complain to their local politicians and newspapers.

For the people who feared the horrors of Tammany Hall politics, the leadership of Greater New York confirmed their predictions of business as usual. The first mayor of the newly expanded city was Robert Van Wyck, the brother of Augustus Van Wyck, NY State Supreme Court Justice, and Democratic candidate for governor of NY, running against Theodore Roosevelt in 1898. The Van Wycks were one of the oldest Dutch families in New York.

Robert was a successful lawyer and man about town, who enjoyed travelling and the good life, and had been Chief Justice of the City Court of New York when chosen to run for mayor by Tammany Hall boss Richard Croker. As mayor, he is credited for bringing order to the many municipal fiefdoms that made up the new city and for approving and championing the first subway line to be built in the city. He also set up the ground work for the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel.

However, for the most part, he is remembered for being a lackluster mayor, chosen by Croker for being the kind of man who would not make waves, or interfere with Tammany’s many other concerns in running the city. In the next election, in 1901, Tammany lost power to Brooklyn’s own Seth Low, who ran under a reformist platform. The New York Times later called the Van Wyck administration as one “mired in black ooze and slime.”

The effects of consolidation were many, some good, some not so much. Transportation and infrastructure improvements improved, with subways, roads, able to cross boroughs and bring people, goods and services anywhere in the city. It took years to coordinate this, but Andrew Green’s ideal of one city did take place. Other municipal services, such as sanitation, police, social services, surface transportation, and other agencies became single city-wide agencies.

One comptroller’s office regulated all the city’s tax rates and budgetary concerns. One central government took the place of many localized governments, with a mayor and other officials supposedly concerned with the well-being of ALL New Yorkers. Greater New York City became the second largest city in the world, surpassed only by London in size and population. Chicago was relegated to “Second City” status and was no longer a threat to NYC sovereignty.

As we all know, however, bigger is not always better. Centralized government became exceedingly Manhattan-centric; a complaint that still is much voiced, over 120 years later. The needs of the “outer boroughs” still do not get the attention of City Hall, and the boroughs will always be the poor step-children to Manhattan. It was never the marriage of equals.

Could Brooklyn have survived as an independent city? Would they be like Minneapolis and St. Paul, two cities across the river from each other, equal in most ways, or more like Philadelphia and Camden, one rich, the other not? Was this ever “Greater New York City”, or was it really “the Great Mistake”? The debate continues….

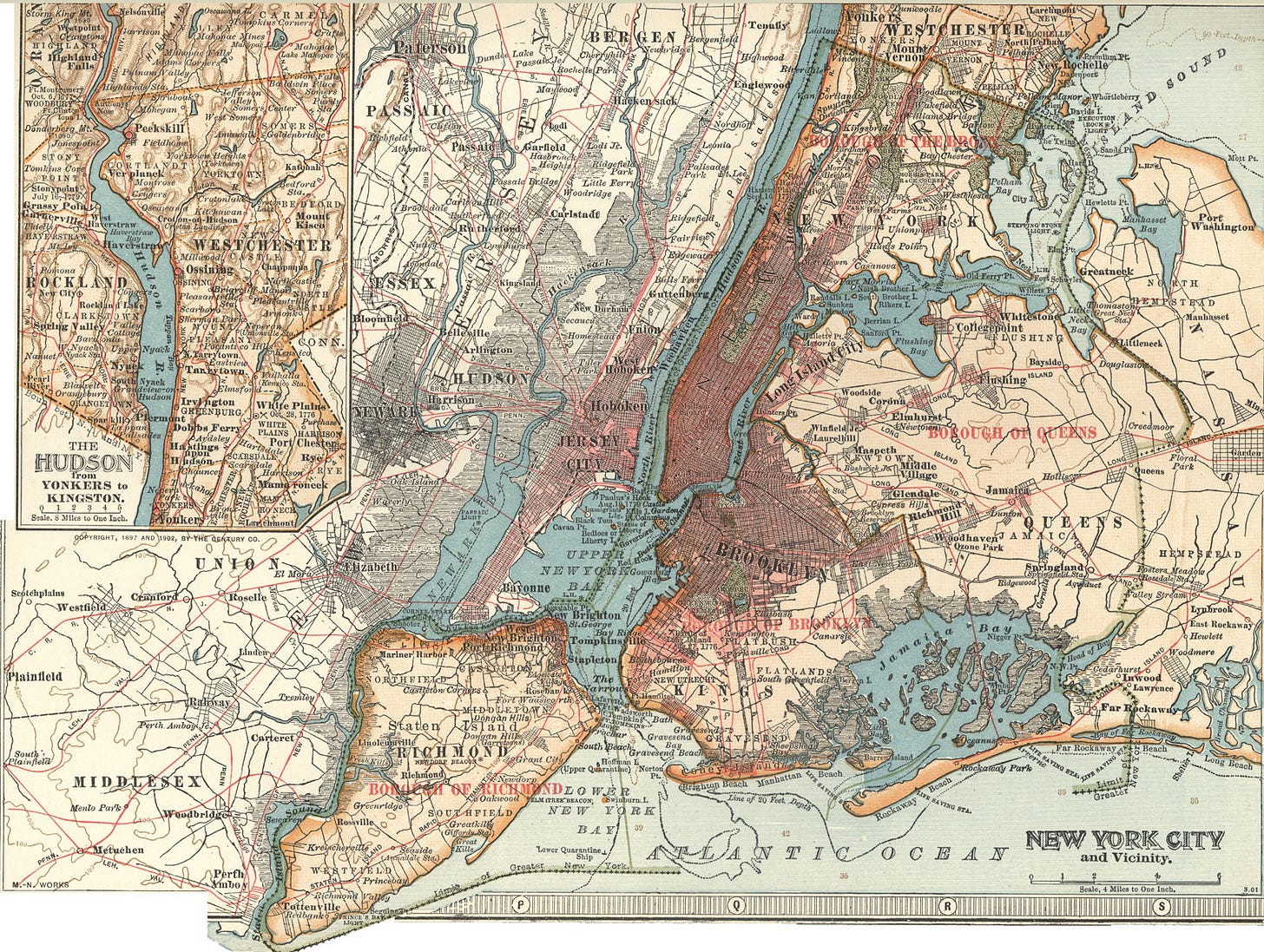

(1898 map of a consolidated New York City. Library of Congress)