The Life and Times of Uncle Frank Erickson, the “Tin-Horn Punk”

In my research I run across interesting characters. Here's one of them.

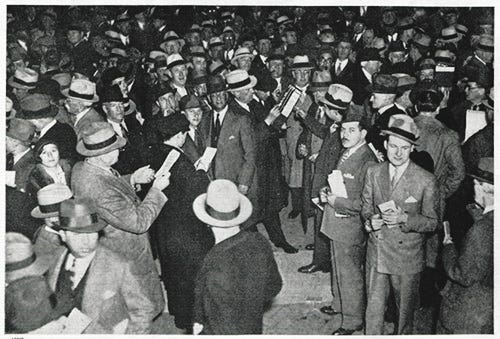

(1930s bookmaking. Photo: sfsu.edu)

We love our mobsters and bad boys in this society. Sure, we may hate their crimes; the murders and the violence, but over a hundred years of American fascination with mobsters in movies, television and books continues unabated. Gambling has always been a part of organized crime. Especially during economic hard times, the temptation to risk a little or a lot of money to strike it rich has been too strong for a lot of people, both the desperate and the risk-takers.

While many people get caught up in cards and games of chance, in the 20th century, the big money was always in horse racing and later, sports gambling. The odds were determined, you laid down a bet with a neighborhood bookmaker, and you said a prayer. If your horse won, you could clean up. If it lost, and let’s face it, for most people, their horses lost, then the bookie kept your money, and you might even owe him more, if you didn’t play the odds right. Of course, either way you were hooked, and you kept playing and paying.

For much of the last century, New York City’s king of the bookmakers was Frank A. Erickson. He succeeded because he was very good at what he did, and it didn’t hurt that he didn’t fit the stereotype of what the public thought the King of Bookies should be. He was a genial and jolly fat man who looked like your Uncle Frank. In fact, he was known as Uncle Frank to all the recipients of the charities he regularly gave to, and he was also Uncle Frank to the children of the famous mobsters whose parents counted Erickson as a friend.

(Frank Erickson. Photo: moviespictures.org)

Frank A. Erickson was born in New York City on November 27, 1895. His mother was Irish, and his father was of Swedish descent. Very early in his life, his parents died, and he spent his childhood in an orphanage. By the time he was a young man, he was working in Coney Island as a busboy in a restaurant. The job didn’t pay well, and young Frank was looking for extra work.

Legend has it that a patron of the restaurant gave him five dollars and asked him to run over to another local bar and place a bet for him on a race at the Sheepshead Bay track. The man sent him out too late to make the bet, as the race was already on, and the horse lost anyway. But Frank Erickson had found his calling. He also kept the five dollars.

He began his life as a bookmaker soon afterward and ran bets in his spare time. By the mid-1930s, he was one of the biggest bookies in New York, and was living like a lord in his new home in Forest Hills at 105 Greenway South, a medieval style banker’s castle he purchased for $75,000. At the time, the average home in a middle-class neighborhood was perhaps a quarter of that amount. Frank also married a girl he met and befriended in the orphanage, those long years ago.

(Erickson house in Forest Hills, Queens. Photo: Wikipedia)

Being the biggest bookie in New York was not without its notoriety, or an association with much more violent criminals and organized crime. The Depression era saw a whole new class of gangsters coming up, and Erickson knew them all, and called many of them friends. Gambler Frank Costello was one of his closest friends. He also hung out with Dutch Schultz and Lucky Luciano. He was the right-hand man of Arnold Rothstein, another Queens resident who was well-known as a kingpin in New York’s Jewish Mob.

Erickson was an extremely intelligent man, and it is said that he and Moses Annenberg, from Chicago, invented nationwide synchronized betting, establishing a country wide wire service where bets could be aggregated from all over the country. Erickson and Frank Costello started the system of laying off bets, which means buying bets from other bookmakers to even the odds and minimize losses. They also set up the lay-off and odds systems still used today by bookmakers.

All this bookie action made Frank Erickson very well known, and very rich. It also made him the target of law enforcement and do-gooder crusading politicians. His career was in the public eye from the 1920s well into the 1950s, during which time he was no stranger to the court system. Between 1919 and 1926 he was arrested for gambling at least five times. The charges never stuck. Reform mayor Fiorello LaGuardia hated him, and called Erickson a “tin-horn punk,” and threatened to have him deported, although technically, as Erickson was an American-born citizen, LaGuardia couldn’t do that.

But he could see to it that law enforcement harassed Erickson any chance they got. 1939 was the year they really started to go after him. In May of that year, the mayor’s office released to the press the results of a lengthy investigation of Erickson and his gambling operations. Much of it was stating the obvious: Frank Erickson was probably the largest bookmaker in the United States, accepting bets from every racetrack in the country. He had an unofficial staff of over 3,000 people across the country, and for many years ran his operation from an office in New Jersey, to sidestep New York City’s gambling laws.

The report also said that Erickson was associating with unsavory criminal types, such as the late Dutch Schultz, Frank Costello, Lucky Luciano, slot machine kingpin Leo Byck, and Brooklyn racketeer Joe Adonis. He also included among his many friends law enforcement officials, politicians, and court officials. One of his closest friends was Brooklyn District Attorney William F. X. Georghan. The two men had been friends for years, and Erickson contributed to his campaign fund.

(Bettors and bookie at a racetrack. Photo: guysanddolls.com)

Since Mayor LaGuardia and law enforcement were never able to get him on gambling charges, they searched for other ways to send Uncle Frank to jail. In 1939 the police arrested him on a charge of vagrancy. Erickson had admitted under oath that his wealth came from being a professional gambler, so an indictment came down to arrest him. They dusted off an old city law; Section 899 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which stated: “Any person who has no visible means of support, or any person who maintains himself for the most part by gaming is a disorderly person.” Disorderly person equals vagrant. The millionaire bookie had been hauled into court on a misdemeanor.

The “vagrant” showed up at the Queens County Courthouse in Rockaway Beach Court on June 12, 1939, after having left his swanky Forest Hills estate that morning in his chauffeur driven limo. He made quite the entrance into court accompanied by his lawyer, Martin W. Littleton, a former Nassau County District Attorney. As Erickson got comfortable in his chair, Littleton presented the judge with a thick pile of stock certificates. The gilt-edged documents represented over $125,000 worth of stock in three of New York City’s largest banks.

“Is a man with this kind of stock a vagrant?” Littleton asked, “I don’t think so.” He went on to argue that his client may have been a bookie on the side, but he was primarily a stocks and bonds trader, and was a Wall Street tycoon, not a back-alley bookie. Littleton also produced a trading ledger showing a long history of trades on Erickson’s account. The Assistant District Attorney, one J. Erwin Shapiro, strongly objected to the stock certificates, as well as Littleton’s assertions that Erickson made most of his money on Wall Street.

The judge, who was a known LaGuardia man, then had each side prepare their briefs. They spent the next three hours bickering in front of the judge, who also added to the drama by declaring that he was his own man, beholding to no one, and able to render a judgment based solely on the facts presented to him. Littleton ended the day with two motions. One for a postponement of the hearing, the other to have the case dismissed because it was frivolous, and the law was archaic and outmoded. The judge denied both motions.

A week after his court appearance for vagrancy, Erickson and his lawyer were back in Rockaway Beach. The magistrate, Judge Irving B. Cooper, found him guilty. He was officially a disorderly person and a vagrant without a legal means of support. Erickson had to post a $10,000 bond and was ordered to stop bookmaking. Theoretically, the reporter covering the case for the Long Island City Star Journal postulated, over 3,000 people who worked for Erickson’s bookmaking operations would be out of work.

By 1940, all of this was over and done. Erickson’s conviction for vagrancy was overturned by a court of appeals. Mayor LaGuardia was not happy. He told the papers that Erickson was “a bum that we don’t want around here.” Frank sat in his mansion and laughed. If they were going to get Frank Erickson, it was going to have to be for something a little more substantive than being a bum and a liar.

In April of 1941, Erickson was at the exclusive New York Athletic Club, where he kept an apartment, when three gunmen gathered outside his door. Erickson and several other men were inside having a meeting. The local scuttlebutt was that Erickson had $100,000 in cash in the apartment. But as the men put their masks on, ready to break in, a chambermaid passed by, saw them, and screamed. She continued to scream as she hauled off and hit one of the gunmen.

They knocked her to the ground and fled as the men came running out of the room. The police gave chase, and trapped one of the men, who shot himself rather than be captured. The other two were also caught and went to prison. Erickson was so grateful to the maid that he gave her a thousand dollar reward, a huge sum in 1941, and arranged for her to get $25 a month for the rest of her life.

The District Attorney’s office was looking into the rumor that a NYPD captain was one of the men at that meeting. A police captain had committed suicide the day after the robbery attempt, and it was thought that the dead captain had indeed been the man at the apartment. The DA’s office held hearings, and one of the people that testified was Milton F. Untermeyer, a very wealthy Wall Street broker who was also at the meeting. He testified that the police captain had been there.

Over the course of the next fifteen years, the courts went after Erickson time and again. He set himself up with a real estate business on Park Avenue, in Manhattan, and also owned a successful flower shop on Madison Avenue. He looked completely legit. In 1952, the state of New Jersey, where all his operations were, got him for breaking gambling laws in that state, and Frank Erickson finally went to prison for a while, spending 14 months in state prison. He had pleaded no contest at his trial.

(Betting on the races. Photo: gentlemen’sjournal.com)

When he got out, his legal battles were not over. He ended up going to Federal prison in 1953 for six months, convicted of Federal tax evasion. He paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in back taxes to both the Feds and the State. After he got out of prison, Erickson seemed to have been defeated. He was no longer in the news and spent his days in his legit business concerns. At some point, he sold the Forest Hills house, and moved into his apartments at the Athletic Club.

By the 1960s, Erickson was now old, tired, and sick. He had bleeding ulcers and a heart condition. In March of 1968, the 72-year-old Erickson went into the hospital for stomach surgery. He never left the hospital. He died before surgery; the cause of death was complications from the ulcers, which led to a fatal heart attack. “Uncle Frank,” the affable, but quite powerful and dangerous King of the Bookies, the tin-horn punk who made Mayor LaGuardia’s head explode, was now gone. Gambling would never again have such a stylish overlord.