(Mutual Bank of Troy side wall, 1st and State Street. Photo: Suzanne Spellen)

One of the most effective warriors against slavery was Harriet Tubman. After escaping from her own enslavers, she singlehandedly traveled from the plantations of the South to the Canadian border more than nineteen times, leading over 300 people to freedom. Her own family members were among the first she rescued, some settling in upstate NY.

Part of Harriet Tubman’s success lay in the fact that most people didn’t know what she looked like. To Southern slaveholders, she was a ghost, blending in as a field hand, disguising herself as an old woman, or a nursemaid or humble servant. For those she helped to freedom, she was called simply “Moses.”

In the spring of 1860, she was slated to speak at an anti-slavery rally in Boston. She was traveling east across New York from Auburn to Boston and decided to take some time to visit her cousin John Hooper in Troy. Not only was her cousin here, but she knew William Henry, Reverend Henry Highland Garnet, Stephen Myers and everyone else in the Capital Region Abolitionist network. She was a general to their army and was right at home in Troy.

Nalle was being held in the cells in the basement of the bank. Martin I. Townsend, a prominent attorney, quickly volunteered to be Charles Nalle’s lawyer. He rushed to prepare a writ of habeas corpus to present to a judge, and thereby get a stay. Charles was brought to the upstairs office of the US Commissioner, who released him to his vindictive half-brother and his slave-catching agent. Wall fastened heavy iron manacles to Charles’ wrists, and planned to lead him out into the street, with Averill and Hansbrough right behind him. From there, they would take a wagon to the nearby train station, and head back to Virginia.

But word of Charles’ capture had spread throughout Troy. Members of the Vigilance Committee had quickly gathered up a sizable crowd. Troy did not like slavery, or those that practiced it. John Brown had been very well received here, and after his execution, his long funeral cortege had stopped in Troy. Contempt for the Fugitive Slave Act was strong.

People had also gotten to know and like Charles Nalle, and they were not going to stand back and allow him to be taken away. As the crowd outside of the Commissioner’s office grew, unbeknown to most, they had a secret and powerful ally in their midst. “Moses” was in the crowd, and she and the Vigilance Committee had a plan.

According to the Troy Times’ account of the story, published the day after the event, the police were afraid to bring Charles down, as it seemed all of Troy was in the street. While they waited to see if it was safe, the Commissioner allowed several townsmen into the office, one at a time, to speak to Charles and offer him encouragement.

A tiny elderly and infirm black woman in a large yellow sunbonnet also pushed her way upstairs. The officers thought she was a relative and let her stay. It was Harriet Tubman, who was not as old or infirm as she pretended to be. Across the street, members of the Vigilance Committee watched from a house’s upper window. If they could see Harriet’s bright bonnet, through the hallway windows, they knew Charles was still in the office upstairs.

The group stayed in the room for so long that some were beginning to think that Nalle had been taken out by another exit, but Harriet’s bonnet was still visible. At one point, Charles had been seated by a window. When no one was watching, he managed to throw open the sash with his elbow and tried to climb out of the window. The crowd went wild with encouragement, but his heavy chains hindered him, and he was dragged back into the room.

William Henry, Charles’ landlord and friend, stood before the crowd and made an impassioned speech about freedom and a man’s right to self-ownership. He told them how Nalle had been brought before the Commissioner shackled as a prisoner whose only crime had been in stealing his own body. He said that Nalle had been condemned to be taken away from his home, his friends and his employer in Troy to be again imprisoned on a cruel southern plantation where he would no doubt be tortured and killed for the crime of wanting to be free.

Could the people of Troy, he asked, permit this good and intelligent man to be so deprived of liberty, a liberty they so freely had in abundance? Would they let a bounty hunter, a vile and low-down slave-catcher who trafficked in human misery, and his employer, a pampered slaveholder from Virginia, win the day? Would they allow Charles Nalle, a man many of them knew and liked, to be dragged back into slavery? The good people of Troy roared “No!”

It was now getting late into the afternoon. At 4 pm, attorney Townsend returned with his writ, which demanded that the marshal bring Nalle before Judge Gould immediately. Whether they wanted to or not, the parties involved had to go down into the street and face the crowd. Deputies were dispatched to make a path. As they went down the stairs, one deputy tried to move the aged Harriet out of the way. He even offering to help her downstairs, but she stood her ground.

The marshal, two deputies, Averill, the slave catcher Wall, Hansbrough and Charles came down the stairs. No sooner had they passed, Harriet threw off her decreptitude, rushed to the window, and shouted, “Here they come,” to the Vigilance Committee watching for her signal across the street. The party came out of the door. Charles Nalle stood before Troy, according to the papers, a tall, handsome white-looking man, weighed down by the heavy chains on his wrists, surrounded by two deputies. His half-brother Blucher Hansbrough was right behind him, the resemblance so strong, it was hard to tell them apart.

The crowd of Trojans, black and white, surged towards the group. Harriet Tubman ran out of the building, pushed one of the deputies aside and wrapped her arms around Charles Nalle’s chained hands, refusing to let go. They were both knocked down, and the mob surged around them, pushing and fighting with the deputies, Wall and Hansbrough. While they were down, surrounded by her people, Harriet took off the bonnet and tied it on Charles’ head.

But not everyone in the crowd was set on freeing Charles Nalle. There was also a contingent that had pro-slavery sympathies, or just liked a good fight, because the scene began to grow more violent, with fights breaking out throughout the crowd. The combatants surrounded Nalle and Harriet, who had still not let go of him. They rose, and with Nalle’s face covered, the master now became the slave, as Hansbrough was mistaken for Nalle, and both parties struggled around them all.

Charles and Harriet were knocked down again. Charles was cut and bleeding heavily from the manacles, and Harriet, who never let go of him, had her coat torn from her, and they had even torn off her heavy boots in the melee. The Troy Times reported that Harriet shouted, “Give me liberty or give me death,” which encouraged the mob even more. The chaos was such that over two thousand people were in the streets, many of them fighting, many more intent on getting Charles Nalle out of there.

The deputies lost Nalle. As they struggled to find him, Harriet and the Vigilance Committee managed to spirit him from State Street, through the crowds, down to the Hudson River. He was supposed to get into a rowboat commandeered for the occasion, but when the rower saw the crowd surging towards the river, he panicked and ran. Nalle made a mad dash for the nearby public ferry and jumped on board. The boat took him across the river to West Troy/Watervliet.

As fast as all of this was, the telegraph was still faster. Warned that the fugitive was coming across the river, the police were ready in Watervliet. Charles Nalle ran from the ferry, a man still in chains, bleeding and battered, found running up the street away from the river. Harriet had not been able to get on the ferry, but was on the one right behind it, but by the time she and her followers got to Watervliet, perhaps only ten minutes behind Charles, he was gone.

A Second and Final Rescue

As Nalle pulled himself up the west bank of the Hudson, and began running along Broadway, the authorities were waiting for him. Exhausted, drained of adrenaline, and seemingly without hope in sight, he was taken away without much resistance. The West Troy authorities took him to a brick building near the ferry dock, to a judge’s office on the third floor, awaiting the arrival of Troy’s marshal and his deputies.

Harriet Tubman never lost a passenger in her entire career as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. She, along with the members of the Vigilance Committee and the citizens of Troy, wasn’t about to start losing one now.

The ferryboat carrying Harriet and three hundred other people was only ten minutes behind him. Harriet and the others ran from the ferry up the river bank, but Charles was gone. A group of children playing by the river shouted, “He’s in that building,” pointing to the brick building by the docks, “Up on the third floor!” The crowd composed of blacks and whites, men and women, surged ahead, approaching the panicking officers of the West Troy constabulary. They rushed up the stairs, and the West Troy police began firing into the crowd, hitting two men, who fell backwards on the stairs, injured but not dead. The crowd kept coming.

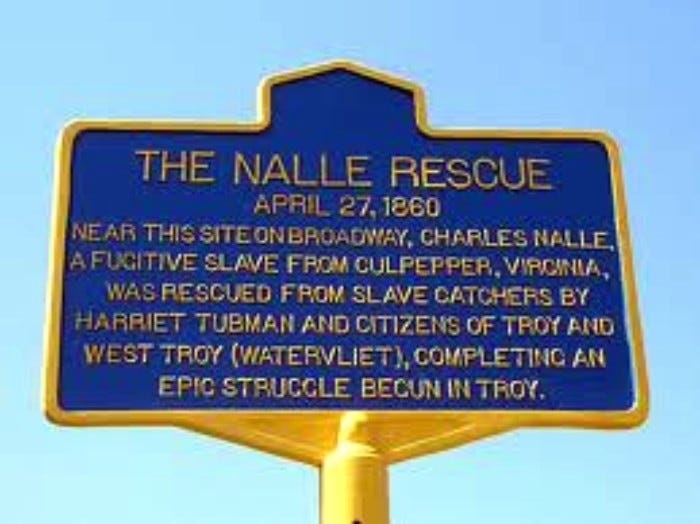

The police were outnumbered, and in the chaos Harriet and her men rushed in and took the exhausted and bleeding Nalle out of the room and down the stairs. According to legend, the five-foot Harriet Tubman, herself battered from the assault in Troy, took Charles in her arms, and like a mother with her child, carried him down the stairs. When they reached the street, a stranger rode by on a wagon. He stopped and asked what the commotion was. When he heard the story, he jumped down from the wagon and offered it to the rescuers. Today, a commemorative marker, erected in 2009, notes the place in Watervliet where the second rescue took place.

Harriet, along with a small number of supporters and at least one of Charles’ friends, jumped in the wagon, and headed west towards Schenectady and the Erie Canal. They stopped in Niskayuna, just outside of Schenectady, where Charles’ chains were struck from his wrists, and the bruised and battered man was hidden until he recovered enough to keep going. He moved northwest to Amsterdam and stayed in hiding for several months.

Meanwhile, his employer, Uri Gilbert, and his friends raised $650 to purchase his freedom from Blucher Hansbrough. Charles Nalle came back to Troy a free man and a hero. He was able to contact his wife Kitty, and three months later, she and their five children joined him in Troy. The Nalle’s lived in Troy through the Civil War years, until they moved back to Washington DC in 1867 to be near relatives on both sides of the family. There, Charles was employed by the Post Office. He died in 1875 and was buried in Rock Creek Cemetery. He never said a word to his children about his life before his freedom, his journey North, or the rescue in Troy.

(Commemorative marker in Watervliet on the site of the second rescue. Photo: Wikipedia)

The Aftermath

After going back to Virginia after his close escape in Troy, Blucher Hansbrough returned to his plantation just in time for the nation to go to war. During the winter of 1863 to 1864, over 20,000 Union troops from the Second Corp of the Army of the Potomac camped on his land. They took over his house as headquarters. He lost everything and died in debt in 1873.

Horatio Averill barely got out of Troy alive. He later claimed that he had not betrayed Charles and offered up several other names as the likely betrayers. No one believed him, the Troy papers did not buy it, and for many months later, were still printing accusations and letters from irate readers. He was warned to never show his face in Troy.

He moved to West Virginia with his brother and made a fortune in the coal business, and somehow became a judge. He returned often to his hometown of Sand Lake where he and his brothers built a resort hotel and speculative community, a venture that failed spectacularly. However, the town of Averill Park bears their name.

Today Harriet Tubman is one of the most famous and admired women in American history. During the Civil War, her uncanny ability to slip past the authorities made her a valuable scout, and she became the first woman to lead an assault during that war. Despite her service to the Union, she was denied pay and recognition by the U.S. Army until 1899. As she grew older, her fame spread, but she lived most of her life in dire poverty, her needs paid for by friends. She died of pneumonia in 1911 and was buried with full military honors in Auburn, NY.

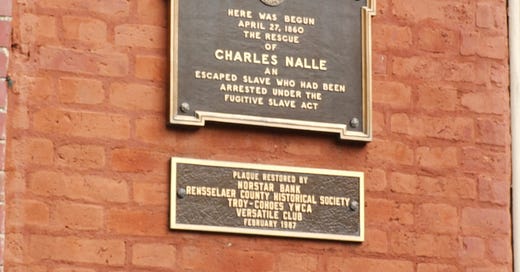

In 1908, the people of Troy placed a memorial plaque on the old Mutual Bank Building. celebrating the rescue as one of the ten most defining moments in Troy’s history.

As Garnet Douglass Baltimore ended his story, he looked at his friend, who had tears running down his face. Garnet had only been a baby, less than a year old when the dramatic rescue took place. John Nalle was only a child of four on that day, still living in Washington with his mother and sisters. The forgotten reporter scribbled in his notebook, taking it all down for the Troy Times.

Of his parent’s eight children, John and one other sibling were the only ones still living. His father never talked about his past. He knew his parents had been slaves, but he had never heard any of the stories regarding his mother’s perilous existence in Washington, his father’s flight to freedom, or of the Great Rescue, or his parent’s reunion.

He never knew that the announcement of his father’s death from heart disease in 1875 had been reported in Troy and Charles Nalle had been remembered publicly with fondness and respect. John Nalle was fascinated by his father’s story, and planned to write a book, but became ill and died soon afterward.

A year later, in 1933, the Sons of the Revolution, a Troy civic group, replaced the plaque with the bronze marker which still marks the place where Troy’s people decided that a man’s life was more important than the letter of the law. That marker was further restored by the Rensselaer Historical Society and others in 1987.

Today, the story of Charles Nalle and his rescue is taught in Troy’s schools and is still regarded as one of the city’s most defining moments. Trojans point proudly to this time in the city’s history when its citizens openly defied the law and fought against injustice and helped save a man’s life.

“Here was begun on April 27, 1860, the Rescue of Charles Nalle, an escaped slave who had been arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act.”

The rescue of Charles Nalle is a celebrated part of Troy and Watervliet history. My research for this story comes from the Troy Times, the Auburn News and information gathered on various websites, much of which is gleaned from the scholarship of Scott Christianson, the author of a very highly researched and detailed book on the subject called “Freeing Charles: The Struggle to Free a Slave on the Eve of the Civil War”. Mr. Christianson’s book was especially helpful with details about Charles Nalle’s early life and the people and places that made up his world.

(Garnet Douglass Baltimore via RPI Alumni magazine)

History is always there, only not everyone can see it. Thanks for a moving tale of a forgotten story.