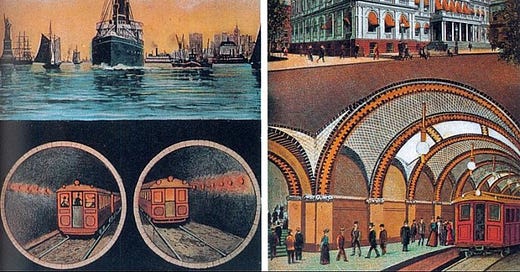

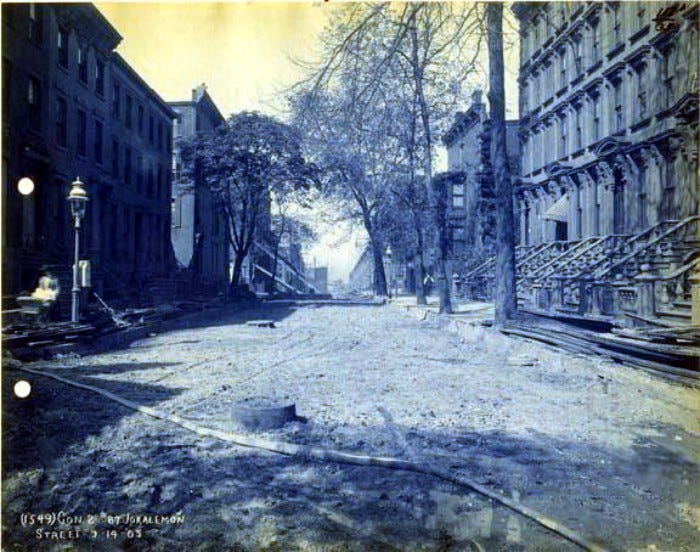

(1907 postcard showing the Joralemon Tunnel, as well as the new City Hall subway station)

At one point, in the mid-18th century, Philip Livingston owned most of Brooklyn Heights. His forty-acre farm once spread across the width of the cliffs overlooking the East River. While the town of Brooklyn was growing quickly below and to the east of him, the Heights were still pasture and farmland, and Livingston’s estate sat on the best part of it. By the time the American Revolution rolled around, Livingston was one of the wealthiest and most influential of Brooklyn’s elite. He was a friend of the patriot cause, and the only signer of the Declaration of Independence from Brooklyn.

After the war, Livingston began selling off parcels of the estate. One of the buyers was a harness and saddle maker named Teunis Joralemon. In 1803, he purchased a good-sized plot, and became one of Brooklyn’s most powerful landowners and important citizens. But Brooklyn was growing, and this hilltop land was more valuable as buildable lots on named streets, than farmland.

Joralemon really didn’t like it and complained bitterly at town meetings. He especially didn’t like some of the people for whom the streets were being named, DeWitt Clinton, chief among them. But progress is progress, and even Teunis Joralemon realized that. Besides, they named an important street after him, a street that would be filled with mansions and fine townhouses.

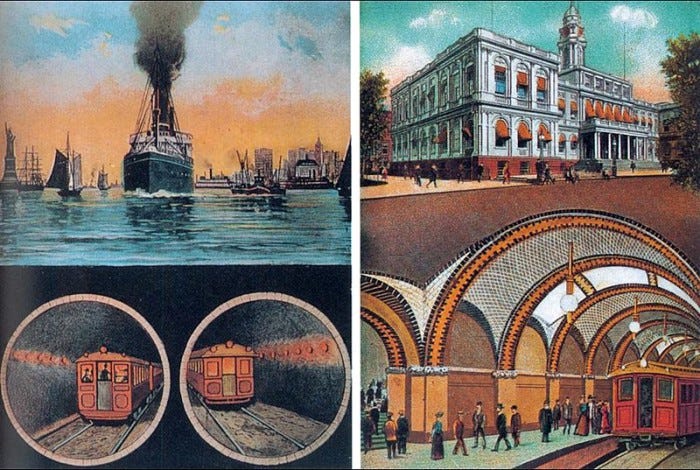

In 1854, a wealthy merchant named John P. Atkinson bought a double sized plot from the Joralemon estate and built a large mansion on the corner of Joralemon Street and Garden Place. 94 Joralemon St. was a large 41 foot wide Greek Revival style house with an impressive columned entryway opening onto the street. In a neighborhood of large houses, at that time, this was larger than most. By 1890, the house belonged to Wilhelmus Mynderse, and it is here that our story really begins.

(94 Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights. Photo: Brooklyn Public Library)

Mynderse was from an old Dutch family whose people settled upstate in Seneca Falls. A lawyer, he was considered one of the foremost experts on admiralty law and had clients around the world. But all of that meant nothing when Progress came to Brooklyn Heights.

In 1903, the ambitious project to dig a subway tunnel between Manhattan and Brooklyn began under the auspices of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, the first underground subway line in Manhattan. Subway transportation between Brooklyn and Manhattan was necessary, and like the Fulton and Wall Street Ferries that had been transporting commuters for 80 plus years, the thousands of commuters travelling back and forth would be well served by this new mode of transportation. It also made sense to have the tunnel stretch under the East River from the Battery to Brooklyn Heights. Now they just had to figure out how to do it.

After much consideration, it was decided that the Brooklyn end of the tunnel would be cut underneath Joralemon Street, and was originally called the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, later changed to the Joralemon Tunnel. The tunnel would consist of two huge parallel cast iron tubes, with a train running in each direction. The engineering for this project would be impressive, as the sandhogs would have to tunnel underneath the river, and through the cliffs that made up the Heights. No one really knew what was under there, or how difficult it would be to construct.

(Red dot in center marks the spot. Googlemaps)

As the Brooklyn end of the tunnel progressed, the homeowners of Joralemon Street started to notice cracks in their plaster walls. In the summer of 1903, the Mynderse’s noticed more and more cracks every day. One night, the family was awakened to groans and rumblings coming from somewhere, and then stopping. They thought it was the wind. The next morning, they found cracks in every wall in the house, and decorative plaster had fallen to the floor.

An inspection outside showed that the house was sinking into the ground, settling as though the foundation had been knocked out from underneath. All the old houses on Joralemon had been settling slowly over the century, that was expected, but the house had sunk two inches the night before, and the walls were in danger of separating, collapsing the house like cards.

Mynderse quickly called his architect, who called the City Engineer, who called the engineers from the tunnel. They all stood around looking at it, perplexed as to what had happened. It wasn’t just 94 Joralemon either, houses up and down the block were also “settling” overnight.

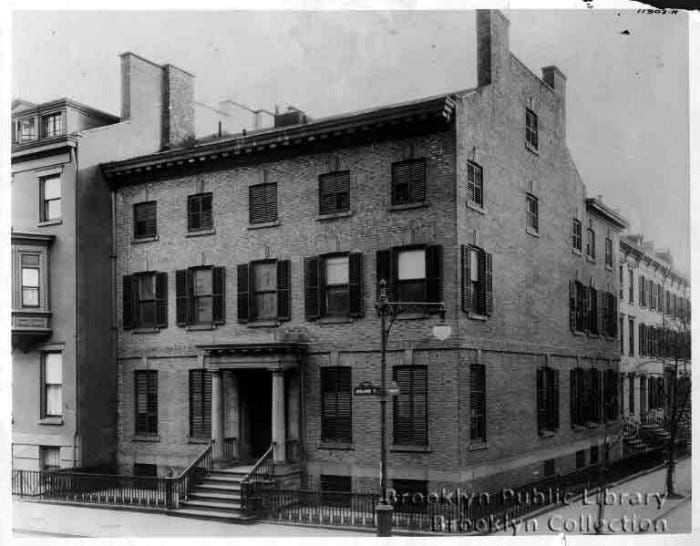

It was theorized that the block sat on a bed of sand, “quicksand” the papers called it, and the tunnel excavation was causing the sands to shift. Mynderse quickly moved to have the building shored up with timbers, and told reporters that if it came to it, he was going to stay in his house until it collapsed. His wife, children and servants probably weren’t as confident of this course of action.

(Brooklyn Eagle photo of 94 Joralemon emergency repair - May 1904)

The winter of 1903 turned into the spring of 1904, and tunnel construction continued. The houses on Joralemon continued to slowly settle, with cracks appearing in everyone’s home, but the Mynderse house was getting the brunt of the damage. The family was still living there, but it was getting worse. Because the house was on the corner, with only one party wall, it wasn’t being supported by the surrounding homes, and it was pulling away onto the street. In May 1904, a huge support system was built on the side of the house to shore it up.

The other prominent people on the block were also being affected, as well. Judge George Abbott lived right next door to 94 Joralemon, and as the house pulled away from his own house, he feared the worse. So did Brooklyn Borough President Littleton, who lived on the corner of Hicks and Joralemon. As the tunnel moved closer to his house, he was worried his corner house would suffer the same fate.

The engineers working on the problem admitted that they were not worried about losing the rest of the houses on the block, the settling would stop, and the damage could be repaired, but they thought they might lose the Mynderse house. The stoop had pulled away from the house, and the front wall had separated, as well.

In a report to the city, on June 17, 1904, the IRT said in that the problems with pressure in the tunnel were being relieved by the digging of a shaft on Joralemon Street. This shaft would also be used to dig the rest of the tunnel underneath the street, making it easier to join the construction coming from Manhattan with the Brooklyn construction.

The Joralemon Street airshaft would alleviate the pressure, and they hoped would also keep the sand from moving around anymore than it had. It would also provide ventilation when the trains were running. The new shaft would stop the houses from being more damaged. Today, that air shaft is hidden in the famous hollow house at 58 Joralemon Street, between Hicks Street and Willow Place.

But soon afterward, the residents of Joralemon Street woke to read some of the most horrific news a home owner can ever read, emblazoned in the Brooklyn Eagle on June 17, 1904; “Property Owners Must Make Their Own Repairs. City not liable for damage done by Joralemon Street Tunnel, so says Transit Board.” They couldn’t believe it. It was like being knocked down, beaten up, and then charged for vagrancy. These were well-to-do, important people. They had never been so abused and outraged in their lives.

As a famed expert on admiralty law, Mynderse was not given to panicked action. But he was a New Yorker. While he was willing to spend what was necessary to save his house, he was keeping his receipts, because there was no way he was going to be paying for this. The City of New York or the Interborough Rapid Transit Company was going to have to write a nice big check when all of this was over. At least that’s what he and his neighbors thought. Mynderse was at the forefront of the homeowner’s group seeking recompense.

The head of the Transit Commission issued a statement saying that their engineers admitted that the contractors working on Joralemon Street had not done as good a job as perhaps they could have. They’ve “obtained the ill-will of many of the property owners on that account,” the paper wrote. But, as the newspaper account continued, Commissioner Orr wrote Mr. Mynderse in a letter to say, “I regret to say that the board finds itself unable to comply with your request.”

“The things you complain of are either the necessary result of the city’s great public work of creating at great public expense what is in fact and law a great public highway: or else due to some negligence on the part of the contractor, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company – or its subcontractors. In either case, as we are advised by counsel, the City of New York, for which this board acts, is not legally liable.”

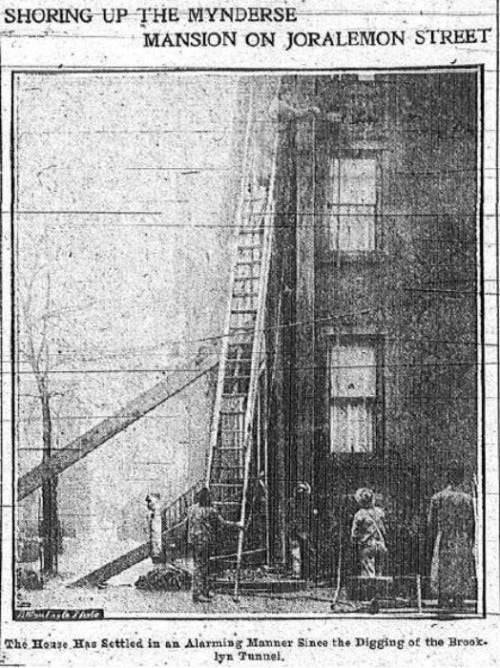

Them’s fightin’ words to any lawyer, and Wilhelmus was one angry lawyer now. He and his neighbors sued. Meanwhile, the construction continued, and so did the problems. Only a month after the letter from the Commission of the Rapid Transit Board arrived, another accident to property occurred on Joralemon Street. After the tail end of a hurricane passed through Brooklyn, with heavy rains, the entire stoop and sidewalk of 45 Joralemon Street tore away from the house and collapsed. There was also extensive damage to the sidewalk and stoop of 47, next door.

(Repair construction along Joralemon. 94 is in the background on left. Photo: NY Public Library, 1905)

The contractors of the tunnel denied that their work was the cause of the collapse, and blamed the heavy rains and the storm. Number 45 had a little courtyard to the side of the building. That slipped entirely off its foundations. The paper noted that the stoop of the house looked like it had been cleaved with a knife; it had cleanly separated from the building. Workmen shoring up the building and stoop had to put up a ladder so that tenants could get out of the house.

Work continued on the tunnel. In March 1905, a miracle of sorts happened in the midst of a disaster. Workmen were installing pressure shields in a portion of the tunnel underneath the river, near the Brooklyn side. One of the shields broke loose and the pressure in the tunnel cause the metal shield to bore through the mud and water to the surface, like a torpedo. The workman closest to the shield was sucked up into the mud and sucked to the surface, as well.

Witnesses said he shot up through the mud and water twenty feet into the air, “performing acrobatics” in the air for a few of the longest seconds in his life, before falling into the water. Miraculously he lived, more amazingly he didn’t have a scratch on him. His fellow workers below were also able to escape through the tunnel to the surface, and only two were seriously injured. This was the first time men had survived a tunnel collapse of this kind. The shield was replaced and the work continued.

(Sandhogs constructing the tunnels. Photo: NY Transit Museum)

In May of 1905, the contracting company hired by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company declared in a city commission meeting that they were not responsible for the damages done to the homeowners of Joralemon Street. The president of the construction company, Andrew Onderdonk, was protesting a proposal in front of the Planning Board that IRT not be paid until the construction company made good on the damages sustained by the digging of the tunnel, and restored Joralemon Street to the condition it was before the tunnel was begun.

Onderdonk protested and said that his company had already approached the homeowners, and was in the process of doing repairs, which he estimated would only cost the, ten or fifteen thousand dollars in total. “I didn’t know of the complaints until a few weeks ago,” Onderdonk told the commission.

How he missed the cracked plaster, shored-up houses and collapsed stoops is amazing, but…he went on to say,” As to the damage we have done, I may state that our counsel advised that we were not liable under the law, and neither is the city. On this our counsel was absolutely clear. However, we held a meeting and decided to do our best by the residents.”

Unsatisfied, the homeowners’ lawsuit against the city and the IRT proceeded. In 1906, the city bestowed four awards to homeowners affected by the tunnel. These awards were test cases to see how the rest of the plaintiffs in the suit would be awarded damages. There were 400 awards on the line, all property owners, business owners and tenants who demanded satisfaction in the case. Wilhelmus Mynderse received the largest amount; $15,000. The other awards were $6,000 to his next-door neighbor, Judge George Abbott, and $12,000 to John Notman who owned 136 Joralemon Street, closer to the river. A fourth award of $1.00 to “an unknown property owner” fulfilled some legally arcane clause of the case.

It would not be enough. At the end of the day, several years later, the case was kicked up to a higher court and the city and the IRT were indeed found liable and paid out over a million dollars to various plaintiffs. The case changed the way the city handled further tunnel building in the future, as well as dealings with the various independent companies that owned the different subway lines. The Mynderse house was completely repaired.

Wilhelmus Mynderse died on November 15th, 1906. He was only 57 years old. He was survived by his wife Hannah and his daughter. He had been the driving force in fighting the city and the IRT to get them to pay for the damages. Although he had received some compensation, most of the settlement money went to his wife after his death. Hannah lived in the house with her servants and two paid companions for another twenty years. By 1927 she had been blind for seven years and had sunken into deep depression.

On May 11th, 1927, Hannah was found dead in her bed, an empty bottle of chloroform liniment by her side. Her companion, a registered nurse, was unable to revive her, and called the doctor. He pronounced her, and a later report by the coroner confirmed it was a suicide. She had left no note. That determination was later changed to a pronouncement of accidental death, caused by her blindness. Suicide was not an acceptable option for the lonely old lady whose family traced back to the Mayflower.

The house at 96 Joralemon Street was sold to the Young Women’s Christian Association and would become the International Institute of the YWCA. The International Institute was a safe refuge for young women from other countries traveling to New York and had many programs to help them settle in a new land. A generation later, the house changed hands again, and today is a condominium with five apartments. No trace of the problems that plagued this storied home are visible today, and visitors still marvel at the home’s size and beauty.

Today, all of Brooklyn Heights is a tourist mecca. People admire the row houses, mansions and that magnificent view of Manhattan. When they walk down Joralemon Street walking towards the harbor, very few realize that they are above the tunnel that almost ate Brooklyn Heights.

(94 Joralemon St. today. Photo: Googlemaps)