Thomas E. Murray, the Genius Machine-Whisperer from Albany Who Made Brooklyn His Home

The story of one of the nation's most prolific inventors and his extended family

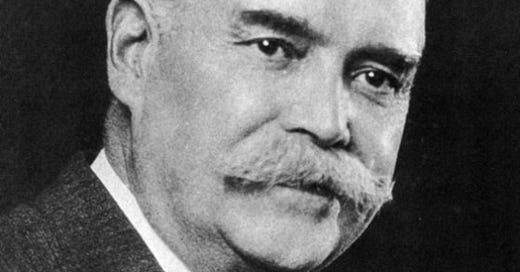

(Thomas E. Murray via temurray.com and Wikipedia)

History can be fickle. We know many who are left out of the pantheon of great achievers in just about every discipline possible. People of color, women and religious minorities have been overlooked or have had their achievements belittled or forgotten for hundreds of years. For some reason, history forgot about Thomas E. Murray, too.

Perhaps because his friend and co-inventor Thomas Edison was such a dominant figure in his day. Or perhaps because people tend to forget who made someone like an Edison as successful as they were, and people like Edison liked to take all the credit. Here is the story about one of the nation’s top inventors, second only to Edison. We use his patented inventions every day. He lived his entire life in NY State and was a classic rag to riches success story, and a family man who never forgot to give back to his community.

Thomas E. Murray was born in Albany, N.Y., on October 21, 1860. He was one of twelve children, the son of a carpenter. When he was nine, his father and two of his siblings died. Young Thomas went to work to support the family, working three jobs. In 1875 he apprenticed at the Albany Iron and Machine Works. Here he learned how all kinds of machines worked, and how to build them. He built his first steam engine that year. He was 15.

Young Murray had a gift; he was a machine whisperer. He was one of those mechanical geniuses who instinctively know how machines and technology work, and how to improve on it. By the time he was a young man, he had caught the eye of the owners of the Albany Waterworks. They made him the chief engineer at the age of 21. He had no formal education in engineering. It was here that he caught the attention of Anthony N. Brady, a powerhouse Albany businessman who was well on his way to becoming a national transportation and energy mogul. He was president and owner of the Albany Municipal Gas Company.

In 1877, he hired Murray to run the gas company. That same year, Murray married Catherine Bradley, the daughter of State Senator Daniel Bradley. According to family lore, they met while singing in the choir at an Albany Catholic church.

While working with the gas company, Murray began inventing things to improve gas production and distribution. He also showed a natural business sense that was impressive in a man of his age and experience.

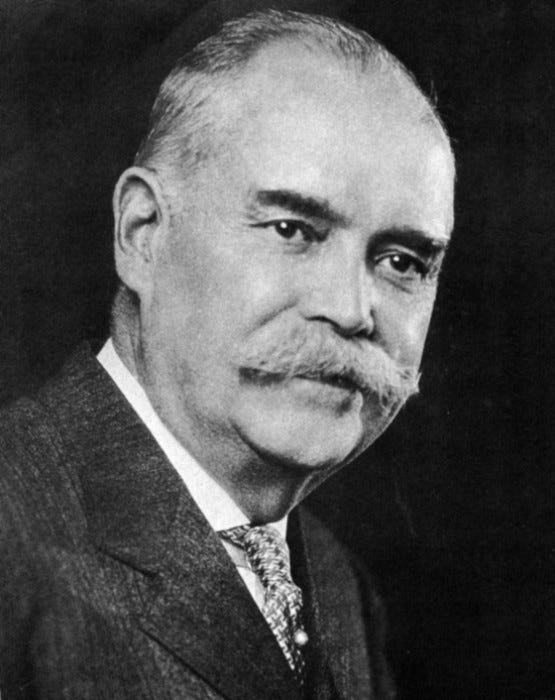

Brady, by this time, was partners with Thomas Edison. He had expanded his energy holdings well beyond Albany to New York, Brooklyn, and throughout the Northeast. At one time, Brady was the richest man in America, with a net worth of over $100 million. He sent Thomas to New York City and Brooklyn to purchase and organize the electric franchises in those cities.

(Anthony N. Brady via temurray.com)

The Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Brooklyn was formed, which later became the Brooklyn Edison Company, Inc. In Manhattan, he united the companies to form the New York Edison Company and the United Light and Power Electric Company. Eventually, they all became one utility called Consolidated Edison.

After Murray had finished putting the new companies together, he was put in charge of all of them — in Westchester as well as Brooklyn and New York City. He was responsible for the building of many of the city’s earliest and largest power stations, many of which are still in use today. They include plants at Gold Street in Brooklyn (1898), Hell Gate in the South Bronx (1921), and the East 14th Street Power station in Manhattan (1926). Murray also electrified the Brooklyn Transit System.

By 1901, the Brady-Edison partnership represented the largest electric and gas monopoly in the world. Murray had his hands full, as the demand for electricity spiked by 32% between 1899 and 1901. He was always trying to find new ways to bring more power to a growing system.

With seed money from Brady, he established the Metropolitan Engineering Company in 1904, with factory space in Brooklyn on Atlantic Avenue. The company made, sold or rented some of the first electric signage on Broadway and other locales throughout the city, and soon expanded to other cities. By 1901, Murray already held several patents for electric signs. In addition to manufacturing products, Metropolitan was Murray’s laboratory, where he could try new ideas and develop new patents.

Murray established several other companies, some of which shared space on Atlantic Avenue, leading to the building of more factory space there, until Murray’s firms took up almost the entire block. Murray owned the Metropolitan Device Company, the Murray Radiator Company, Murray Manufacturing, and Thomas E. Murray, Inc.

(Ad appearing in the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper, 1911)

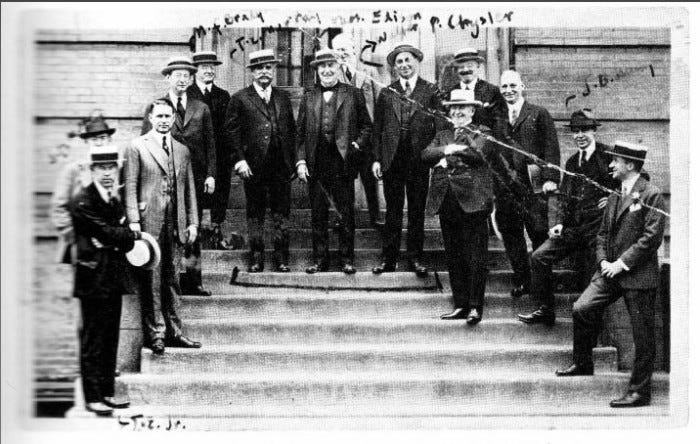

By 1908, the Metropolitan Engineering Company had 11 patents to their name, all Murray inventions. Some of his inventions are so familiar to us; we forget that at some time, someone had to come up with them. They include electric switches, fuses, meters, light sockets and insulated wiring. Through Murray’s association with Anthony Brady and the Edison power companies, Thomas Edison was a frequent visitor to the Murray household and businesses. Edison came to Brooklyn on official visits several times, and always stopped by Metropolitan Engineering. Thomas Murray posed on the steps of his factory with Edison and Brady at his side, along with Walter Chrysler.

Murray and his growing family lived in Brooklyn. Thomas and Catherine had eight children, four boys and four girls. The Murrays were devout Catholics, and as their fortunes grew, they generously gave their time and money to Catholic causes, especially the establishment of orphanages, hospitals and old-age homes. Catherine Murray was very active in fundraising for various causes throughout her life.

(The Murray family, via temurray.com)

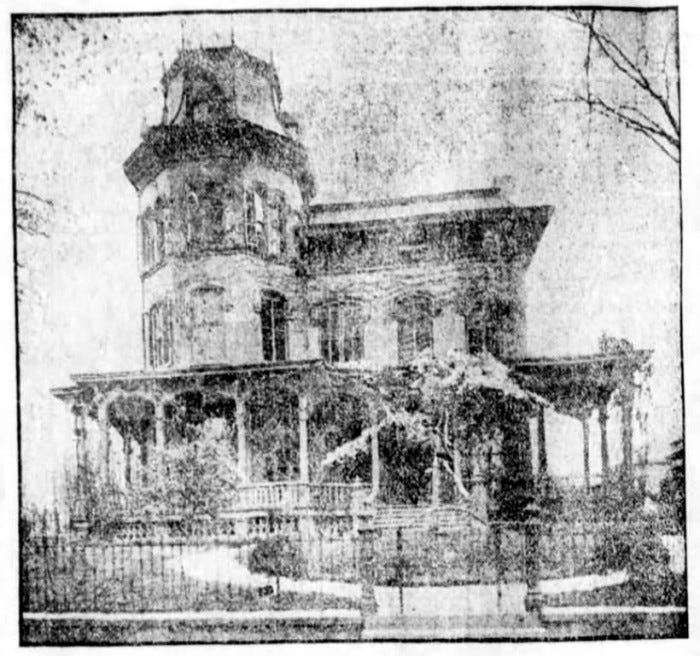

By 1913, the family had moved to 783 St. Marks Avenue, in the prestigious St. Marks District. The wood-framed mansion was one of the oldest houses on this street of new, enormous estates. It was between New York and Brooklyn Avenues, the most prestigious block on the row. Their neighbors included some of the richest people in Brooklyn, which was fitting, as the Murray clan were also quite wealthy. Papa Murray was pretty low key, as rich guys go, but subsequent generations would change that. The house stayed in the family for several years past Thomas’ death in 1929.

In the spring of 1920, Villanova University in Pennsylvania bestowed an honorary degree of Doctor of Science to Thomas E. Murray. He must have been thrilled, since he had been a working man supporting his family since the age of 10 and had never had the opportunity to go to high school, let along college. His success was a testament to hard work, self-improvement and genius. Although Thomas Sr. had many business ventures beyond his work for the power company, he was, first and last, a prolific inventor.

His children received the educational opportunities he never had. His eldest son, Thomas E. Murray, Jr. graduated from Yale, and was also a mechanical wizard. He would take over the companies after his father’s retirement or death. Another son, Joseph also had the gift, and worked with his father. His daughters were doing well in marriage and family; the other boys were successful in school and work. He and his wife were on the boards of several charities and gave generously of their time and money. Thomas was famous for saying, “When charity is accompanied by publicity it is not charity; it is advertising.” He was never one to toot his own horn.

(Murray family home at 783 St. Marks Avenue. The house was torn down in the 1930s for an apartment building)

The Murray family parish was St. Gregory the Great, on Brooklyn Avenue, a fine new church building built in 1915. They and other wealthy Irish Catholics in the St. Marks District contributed greatly to the building and furnishing of the church and adjoining school. Because of the family’s devotion and generosity to Catholic causes, the Murray mansion had a private chapel, complete with a small pipe organ and an altar. That was special enough, but they also were one of a very, very few families allowed to have mass and to take Communion in the home. That privilege illustrates the heights to which the family had risen in the eyes of the Church.

(Thomas Murray, center left, with Thomas Edison, center, and Walter Chrysler, center right. Photo taken in front of the Atlantic Avenue factory)

Thomas Edison made another visit to Brooklyn in 1921. He was here to see a new invention of Murray’s. As he watched, two halves of a housing were welded together in a second. The process was another Murray patent. Edison was delighted, saying “You can do things I cannot!” Two years later, Murray patented a process that Edison also saw that day, a machine that sent an electric current through glass or porcelain, welding it to metal in seconds. This procedure had been attempted since the Egyptians, with more failure than success. Because of this major advance, we have modern spark plugs, fuses and electric sockets, among other things.

Murray excelled at inventing processes and manufacturing tools that joined disparate components together. He had a remarkable intuition and understanding of substances, metallurgy and the power of electricity. The joy was in figuring out how to do something that couldn’t be done before and making that process cheap and available to other technologies. Murray applied that knowledge to all sorts of mundane uses; double threaded pipe couplings, new kinds of radiators in their radiator company, or coming up with the first electric dishwasher, or the now-familiar chains that slip onto tires for traction in the snow.

(Thomas Edison at table, left, TE Murray at table, right. 1908. Photo via temurray.com)

All was going well for the family until the first week in May in 1926, when Catherine Murray contracted pneumonia. Several days later she died at home on St. Marks Avenue. Her devastated family attended her funeral mass at St. Gregory’s and laid her to rest at Calvary Cemetery.

Afterwards, Thomas Sr. began to slow down. The family had just purchased a large summer “cottage” in Southampton, Long Island, which they named Wickapogue. He and his large family spent a lot of time there, part of a growing colony of rich Irish Catholics.

In 1928, Murray resigned his position as chairman of New York Edison. His health wasn’t what it used to be, and it was too much. He kept up with the company affairs, as well as the affairs of his other four corporations on Atlantic Avenue. He continued to invent, racking up more patents towards the end of his life than he had in the past.

By 1929, America was on the window ledge of economic disaster. Thomas Murray headed out to his beloved Wickapogue with family. His eight children had given him dozens of grandchildren, and the elder Murray, who was a short, round and genial grandfather, has his hands full. He had not been particularly well for the last few months but was confident that his time on Long Island would be a cure. On July 21, 1929, Thomas E. Murray died at Wickapogue at the age of 69.

(St. Gregory the Great RC Church, St. Johns Place at Brooklyn Avenue, Crown Heights North. Photo: Bridge and Tunnel Club)

His body was brought back home to Brooklyn. His funeral and requiem mass at St. Gregory’s brought out dignitaries, industry heads, and prominent Catholics from all over. The funeral cortege left his home and made its way to the church, only about three blocks away. The service was officiated by the Bishop of Brooklyn, Thomas E. Molley. In attendance were ex-Governor Alfred E. Smith and his wife, Mayor James Walker, and a host of other city officials.

Also there were the heads of some of the city and nation’s most important businesses, and representatives of the many charities and organizations that the Murray family supported. There were also workers from his plants, friends and neighbors from Albany, Long Island and all over New York. The large Murray family was there as well, of course. The great church was filled to the rafters, all there to say goodbye to a great man.

Thomas Murray had been made a Knight of St. Gregory, a papal honor going back centuries to the Templars. He was also a Knight of Malta. Both orders were honors bestowed only on Catholics who had been altruistic examples of faith, charity and nobleness of spirit. Thomas Murray had certainly been that. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery next to his beloved Catherine.

Murray left a body of work that included 1,100 patents under the Murray name. He also left a massive estate worth over $11 million. His son Thomas Jr. took over as head of the businesses. He was a master of invention himself, a better businessman than his father, and a champion of charity, as well. His brothers were also involved. Their parents now gone; the Murray family remained in Brooklyn for only a hot minute. The palatial towers of Park Avenue were already calling.

Thomas Jr. wasn’t the only smart Murray son. His younger brother John was also an engineer. He lived at 169 Rugby Road in Flatbush with his family. In January of 1929, he was appointed by Governor Theodore Roosevelt to a position on the board of the powerful Port Authority of New York, due to his engineering expertise.

(Former Metropolitan Engineering Co. and other Murray companies HQ. Atlantic Avenue, Crown Heights North. Photo: Rebecca Baird-Remba. This is within easy walking distance to the family home on St. Marks Avenue)

When World War II broke out, the War Department came to Brooklyn to talk to Thomas and his brother Joseph. The two men had overseen operations during the first war, when the company was the country’s only manufacturer of 240mm trench mortar shells. Now their country needed them again.

Those shells were needed again, as were three-inch Stokes mortar shells and other ordinance. The Murrays, through patented welding technology, were the fastest and most expedient shell manufacturers in the country at that time. To handle to massive production, the company opened two new factories in East New York.

Meanwhile, as success followed the Murray family in business, their social standing and success was matched by very few in the country at the time. They were Irish Catholic aristocracy. They were lauded and written about in the society and gossip columns of New York City and Southampton, Long Island. The family became part of what was called the “Golden Clan,” a group of extremely wealthy Irish Catholics who summered in Southampton and made news in the society pages, on Wall Street and in the halls of power.

The Murrays and another family, the McDonnells were at the top. The McDonnells’ fortune was derived from stocks and banking, among other interests. Thomas Jr.’s daughter Anna married James McDonnell, joining these two clans into a huge, blended family. Given that the McDonnell scion had 14 children and Thomas had 11 — and many of his brothers and sisters also had large families — this was going to be an enormous family.

(Cover of “The Golden Clan,” by John Corry, written in 2020)

Thomas Jr. built his own large house in Southampton, near where his father had built Wickapogue decades earlier. Joseph built his own castle in nearby Water Mill; others, including his brother John, followed suit. The papers ate this up, and the gossip flowed as to what these rich, good-looking people were doing out in Southampton.

Like the Boston Kennedy clan — whom the Murrays all knew, of course — the Murray-McDonnells were the talk of society and those who cared what rich people were doing. And what they did was build big, have more children, and build even bigger. They summered a lot, invited prominent clergy to hang out with them, rode polo ponies and show horses, and looked good. Basically, they looked and acted like a Ralph Lauren commercial on steroids.

Over the next 30 or so years, the papers were full of Murray-McDonnells and their spreading families. One of the McDonnells married Henry Ford II. One of the John Murray’s daughters married Alfred G. Vanderbilt II. After World War II, Thomas Jr. was appointed by President Truman to the new Atomic Energy Commission.

The family had long ago left Brooklyn for the towers of upper Park Avenue, near their favorite churches, St. Ignatius of Loyola and St. Thomas More. Slowly, as the second half of the 20th century progressed, the Murray children passed on, and the subsequent generations either lost much of the family money or just got very quiet about it.

The Murray family today is still huge. But the legacy of great-grandfather Murray was lost to history and lost to his family. In 2008, his great-grandson Sean Murray McGuire and some of his cousins pooled together long-lost information and made an effort to bring Thomas Murray back into the spotlight. Through their efforts, Thomas E. Murray was finally inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame and is prominantly mentioned on Wikipedia and in search engines. Today, that’s about as “found,” as one could be, and hopefully more people will learn about him.

Several years ago, I met one of the family members, Lucy, who attended one of my walking tours in Crown Heights North. She was looking for her great-grandfather’s house on St. Marks Avenue. An apartment building stands there now. She told me a bit about him, but I didn’t realize he was THAT Thomas E. Murray until this article first appeared as a series on Brownstoner in 2015.

I also heard from Sean McGuire and Tom Murray, the grandson of Thomas E. Murray Jr. and great-grandson of patriarch Thomas E. Murray. Both were grateful for the family attention, some new information they hadn’t yet uncovered and had nothing but kind remarks.

Tom Murray and I became friends. He’s an Emmy-winning independent writer, film maker and producer. His documentary about his family and his brother Christopher called “Dad’s in Heaven with Nixon” introduced us to his immensely talented younger brother who was diagnosed with autism as a child. Today, Chris is a respected artist, collected by art lovers. The well-reviewed film was aired on Showtime in 2012, before my articles were published. It’s available on Amazon.com and is well worth watching.

He and his sons attended one of my Crown Heights North walking tours, and last year, Tom and I met here in Troy to talk about researching his great-grandfather’s life in Albany. That a man raised on Park Avenue, descended from “American Irish royalty.” and an African American woman from a small town in upstate NY shared a common interest and became friends is one of the wonderful things about what I do.

It has been my pleasure to shine a spotlight on Thomas E. Murray, he is well-deserving of much greater attention. I’m hoping Tom will film a new documentary, one about his amazing great-grandfather. It will be a must-see for me!

(Macy’s Department Store, by Chris Murray, 2005. via mutualart.com)

Your piece on Murray, which I came upon this evening, is great fun to read. I know his great grandson well and knew his father, too -- James B. Murray -- who would have been, of course, Thomas' grandson. The genes involved must be formidable, since the two Murray's I've known led notably accomplished lives.