Garnet Douglass Baltimore: A Son of Troy

We shouldn't have to wait for Black History Month to highlight important men and women who made American history. Today, I'd like to introduce you to a great man and his family who lived in Troy, NY.

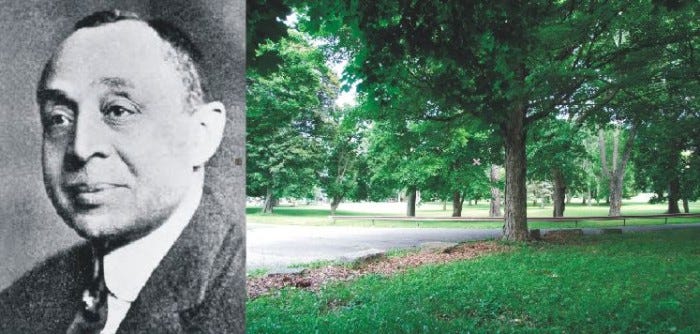

(Garnet Douglass Baltimore and his Prospect Park, Troy)

Garnet Douglass Baltimore is Troy, NY’s most well-known African American citizen. There is certainly good reason for that – he was born and raised here and during his lifetime accomplished great things in this city. His accomplishments can be seen around us today, even though he was active at the turn of the 20th century and died almost 80 years ago.

He was a man of many “firsts.” In his business and social life, he was not just a “first,” he was an “only,” up until the end of the 20th century and beyond. One of the things that he wasn’t was a diarist, or someone who spoke much about himself in print or otherwise. So, while we know of the man and his deeds, we still really don’t know him. He remains an enigma. I hope to be able to someday fill in some blanks. But in the meantime – here is his inspiring story, and for that, we have to start sometime before his own beginning.

Baltimore was born in Troy, NY, that small city just upriver from the state capital of Albany. Once part of the patroon (feudal lands) of 17th century diamond merchant and Dutch West India Company co-founder Killian Van Rensselaer, the village of Troy was established in 1787. Because of its location on the Hudson River, Troy initially developed as a trading town, a nexus point between Boston and New England to the east, Canada to the north, western NY and the Great Lakes to the west and the Hudson River towns and New York City and its harbors to the south.

As the 19th century progressed, Troy became an industrial center. An abundance of fast flowing water feeding into the Hudson from two creeks that run through the city led to textile, paper and other mills, and most importantly, a large and important iron industry. Troy was an educational hub as well, with important schools, including Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), the oldest technical college in the country. It was founded in 1824 by Stephen Van Rensselaer, Killian’s descendant.

Around the time Van Rensselaer was establishing his institution, a woman named Hannah Lord Montague invented a detachable collar for her husband’s shirts. The idea took off like wildfire. By the time Garnet Baltimore was born, in 1859, Troy was a rich city, prospering from its position on the Hudson River and the Erie Canal, from iron and steel, its educational institutions and from the manufacture of millions of detachable, starched and pressed shirt collars.

Garnet’s family saw Troy’s beginnings. His grandparents, Samuel and Phebe Baltimore were free people of color who came to Troy in the early 1800s. They, like many others, came west from New England. Samuel and his wife ran a popular seafood restaurant, with oysters as their specialty. Their youngest child was Peter F. Baltimore, Garnet’s father.

(A young Peter Baltimore, 1840s. This is a rare portrait of a free black man from this period. It is now a proud possession of the Hart Cluett Museum in Troy)

The Capital Region had a small but established black population in the mid-1800s. But even though they enjoyed relative peace and success, no one could be truly free while slavery existed in America. Fighting slavery was not just a moral decision for many, it was a duty. Troy’s black Abolitionists were joined with those in Albany and the surrounding region.

The now-famed Abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet came to Troy in 1840 and was named the pastor of Troy’s Liberty St. Presbyterian Church for Colored People. From his pulpit, Garnet honed his skills as an orator, and was renowned for his inspiring speeches on freedom, equal rights and temperance. He became a mentor to Peter Baltimore, a teenager in those early years, and Peter often accompanied him to NYC and elsewhere for speaking engagements. Troy’s anti-slavery activities would grow in the years to come, especially after the Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1850, allowing slave catchers to come north to capture escapees, and making it illegal for anyone to help in their escape.

Peter became a barber and established an upscale “tonsorial resort” called the Veranda. His emporium was popular with Troy’s wealthy movers and shakers and was known as a place where they could be expertly groomed while relaxing with their peers, engaging in discussions of the day, with Peter as a knowledgeable, popular and gregarious host. What none of his customers knew was that the Veranda was a major stop on the Underground Railroad. Many of those quietly sweeping up or working in the shop or the hotel next door were escapees, bound for Canada. Baltimore was hiding them in plain sight.

Baltimore’s anti-slavery activities and his friendship with Rev. Garnet brought him into contact and friendship with Harriet Tubman, who had a cousin living in Troy, as well as with Frederick Douglass and other Abolitionists who spoke in Troy. When his youngest son was born, Peter and his wife Caroline named him for the family heroes – Garnet Douglass Baltimore.

Garnet was a child during the Civil War. He and his brother were educated at the William Rich School for Colored Children, founded by another successful black barber with a wealthy white clientele, who was also an active Abolitionist along with Garnet’s father. Troy may have been proud of its anti-slavery stance and activities, but the schools were still segregated. The Rich school was the city’s black school.

The school started out with black teachers and administrators, but by 1872, it was being run by a white minister who told his students that they shouldn’t aim too high, as they were fit only for lesser positions. Undeterred, Garnet and his brother were urged by their parents to apply to the prestigious Troy Academy, the school for the city’s rich boys. It had never had a black student. But they soon would, as both boys were admitted, becoming the first African American students in the school’s history. Garnet studied there for five years, intending to go to Harvard.

But in 1877, he decided that he was more interested in mathematics and science than classical studies, and applied for admission to RPI, located not far from his family home. He was accepted, and in 1877, joined the 44 members of his class as the first African American student at the school. He graduated in 1881 at the top of his class, excelling in math, surveying and drawing, all tools needed by a civil engineer.

(RPI in 1876, drawing from “A History of the City of Troy”)

The day after graduation, he was appointed the assistant engineer for the construction of the Albany and Greenbush Bridge, at the time, the most important engineering job in the area. He became very proficient in railroad engineering and worked on several important railroad projects. But he would have to travel far from his family and hometown for his next assignment.

In 1884 he was appointed assistant engineer for the NY State Canal system, personally hired by the State Engineer and Surveyor. Garnet’s first assignment was as engineer in charge of the construction of the Shinnecock & Peconic Canal in Suffolk County, Long Island. After the canal was completed, it was back upstate to work on the locks of the Oswego Canal, an important small canal with a direct connection to Lake Ontario, connecting it to the Erie Canal northwest of Syracuse.

The Geneva NY Gazette newspaper heard of the canal appointment and wrote, “One of the most successful young colored men in the country is Garnet D. Baltimore, a civil engineer who graduated some years ago at the Troy Polytechnic Institute. He now has charge of the enlargement of canal locks near Syracuse. His father is a barber who clips locks in Troy.”

The Oswego’s problem lock on the route was Lock 5, which was built on quicksand and mud. Over the years other engineers had tried to stabilize it and failed. So, they gave it to Baltimore in 1887. After studying the problem, Garnet figured out how to stabilize the underlaying mud. He used a system of deep pilings, a new cement mixture he concocted and a novel way of using the instability of the soil to work against itself. It was a marvel of engineering. If anyone doubted that the “colored” engineer knew what he was doing, they doubted no longer.

But Troy was calling its son home. By 1891 he was back in Troy with a new job with the city as Assistant City Engineer, and a new wife. He met and courted Mary E. Lane on Long Island, while working on the Shinnecock canal. They waited three years and were married on June 18, 1891. Papers across the state wrote about the wedding because Mary Lane was the daughter of a prominent Nassau county family. She was also white.

Since it was inconceivable to many that a prominent white family would welcome a Negro into the family, rumor had it that Mary and Garnet ran off and eloped. But the Lane family proudly announced that they and the Baltimore family approved of the union. The Albany Morning Express must have been in quite a tizzy because they got Garnet Baltimore’s name wrong, they named his father, and they got his higher education completely wrong. Take a look at the article, it’s one of the very few to ever mention his race.

Baltimore was a workaholic and throughout his municipal career also took on other jobs. He accepted a job with a group of businessmen who wanted to establish a large, new for-profit cemetery on the outskirts of Troy. Forest Park Cemetery was going be “one of the most beautiful and attractive cemetery properties in the state,” according to their sales pitch. Baltimore was named the surveyor/architect/engineer for the project. He worked on the project for three years.

There was already a cemetery on the chosen site, so Garnet incorporated it into his design, as an enormous park, with winding trails, landscaping and a large receiving tomb near an ornate entrance gate of his design. Unfortunately, the businessmen had no idea how to run a cemetery, and the operation went bankrupt several times. Baltimore’s plans were never completed, except for the tomb and gate. They are still there, on Parkwood Avenue. Most of the land is now the Troy Country Club’s golf course.

(Cleveland Ohio Gazette dated 1890)

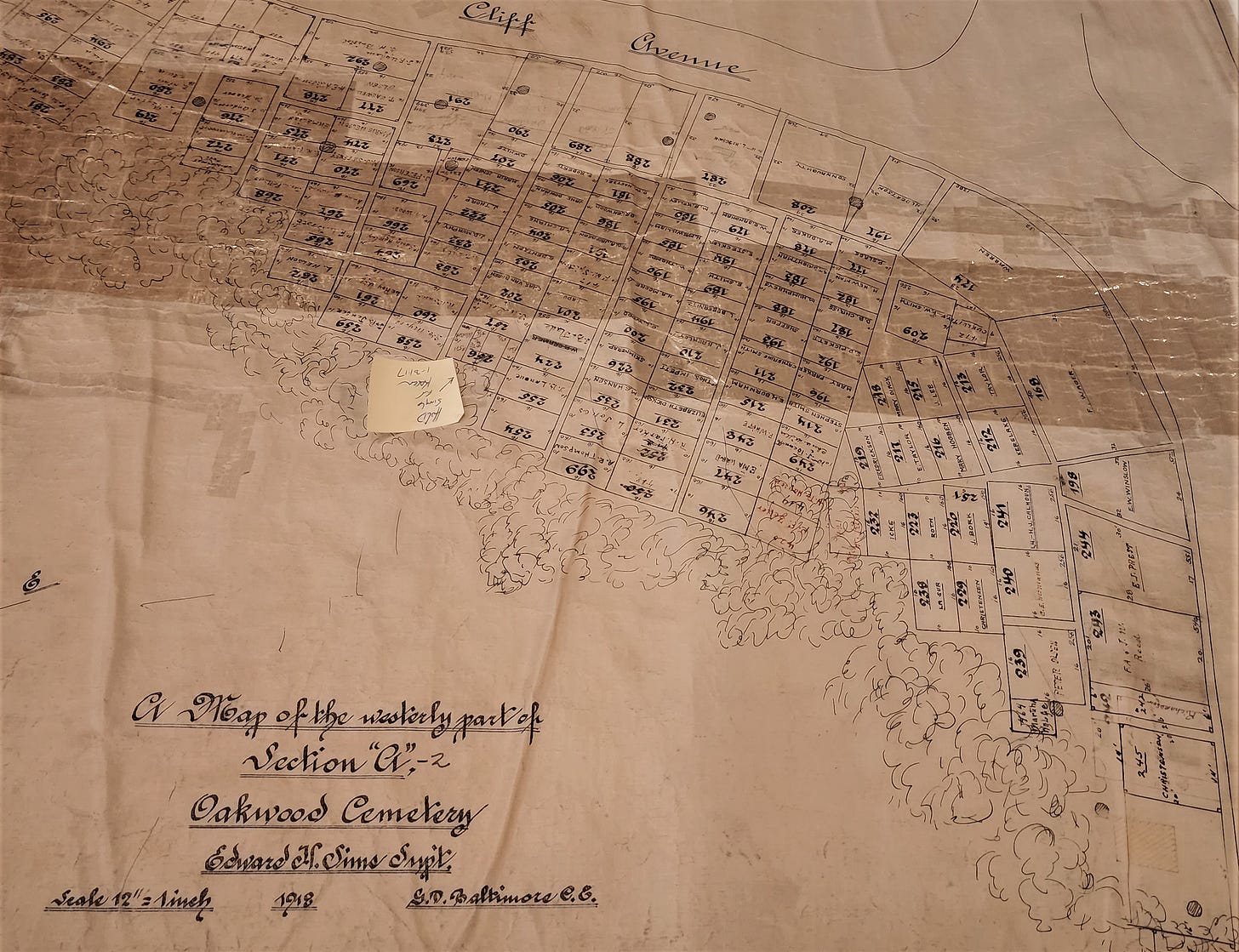

Even though Forest Park was unsuccessful, people had nothing but praise for Baltimore’s designs and ideas. He found himself in demand for other cemeteries and was appointed the architectural engineer for Troy’s Oakwood cemetery, the city’s beautiful non-sectarian park cemetery, high on a hill above the city. Like Brooklyn’s Green-Wood and other park cemeteries, Oakwood has miles of pathways, with planting beds, many species of trees and shrubs, with lakes and a waterfall, all surrounded by headstones, large monuments and mausoleums, the resting place of the city’s elite and everyone else too, regardless of race, creed, color or income.

Baltimore laid out several new sections of cemetery, his original signed drawings still a part of Oakwood’s records. Other cemetery jobs followed, including Graceland Park Cemetery in Albany, as well as cemeteries in Hoosick Falls, Glens Falls and Amsterdam, NY. While he was laying out new sections of the cemetery, he purchased a family plot for himself, where his parents, siblings he and his wife would someday rest.

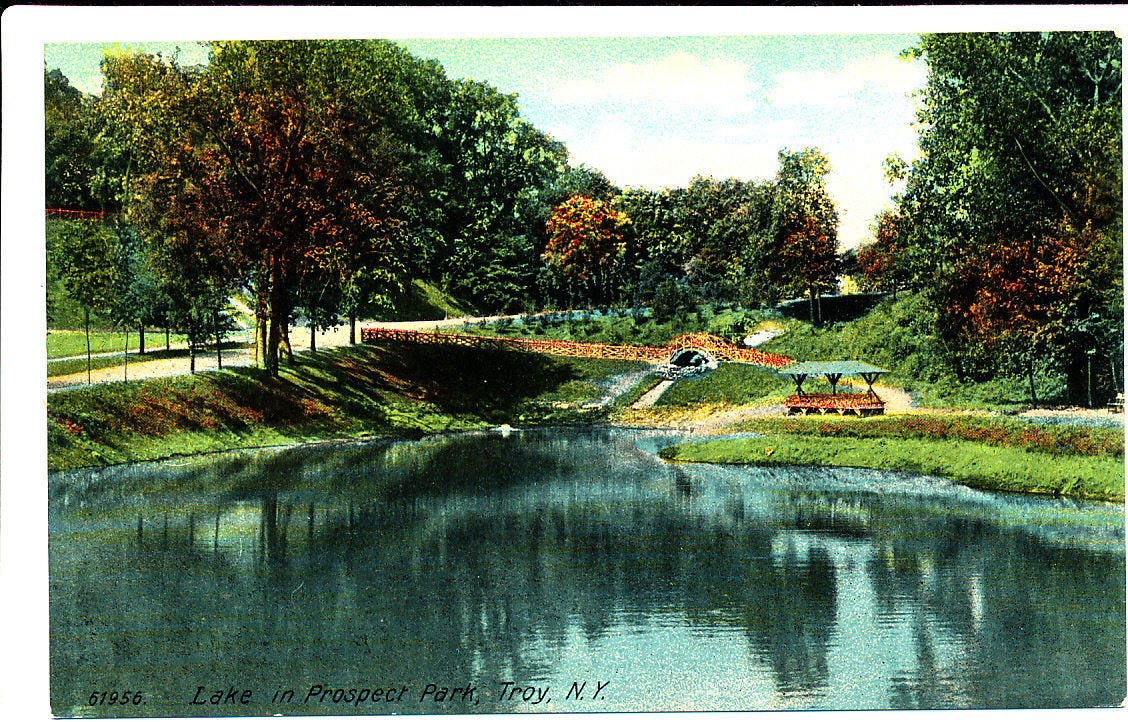

When Garnet D. Baltimore’s name is mentioned in Troy’s history, it is generally in connection with Troy’s Prospect Park. After hearing about the success of Central and Prospect Parks in Manhattan and Brooklyn, Troy wanted a large, beautiful park too. Every modern and successful city had a large municipal park. Parks were also seen as necessary to good health and a respite for Troy’s working class, which toiled in factories from sunup to sundown six days a week. But because Troy is nestled between high hills and the Hudson, there wasn’t any available land in the city proper, only on one of the hills overlooking the city.

After a long and contentious battle with the various political and moneyed committees, the location of the park was decided – the old Warren and Vail estate high on the hills of Mount Ida, overlooking the southern part of the city. Garnet Baltimore was charged with the design and implementation of plans for this very important park. He toured parks in New York, Boston and New Haven and came home with ideas for what would be named Prospect Park.

Left to his own devices, Baltimore would have meticulously planned, landscaped and constructed everything he wanted for the park, including vital infrastructure, amenities and recreational features. But the city overruled him, jumped the gun, and opened on July 4, 1902, before anything was completed. They just threw open the newly installed park gates and let the people in. Baltimore was appalled.

He wrote to the city, saying, “No effort was made to make the surroundings attractive or inviting. It is imperative that no feature be tolerated which would tend to cheapen or belittle the character of the park.” Baltimore and his crews worked on the park until 1906, when he left it in the hands of the Parks Department. He continued to write reports for years afterward, as part of his position as consulting landscape engineer. Over the years they would continue to disappoint him, especially in the last years of his life, as he watched the park deteriorate.

Despite this, he truly loved Troy, and was involved in many different improvement projects over the years. He was an eloquent spokesman for the growth and beauty of the city and gave lectures and slide shows to local clubs, civic and church groups. He designed a plan for creating a civic center in the middle of downtown, but it was never acted upon. He was always working, becoming the city’s consulting engineer, often called upon to testify in court cases, both civil and criminal. He worked for outside attorneys and was hired by other municipalities and lawyers across the state. Preparing materials for court testimony and acting as a consulting engineer for cemeteries became his bread and butter after the end of his tenure with the city.

In 1941, Garnet Baltimore placed an ad in the Troy Times Record, looking for new projects. He was 82 years old. In 1943, he celebrated his 84th birthday, an event covered by the newspapers. They wrote of his family history, his education and many achievements. He received the well-wishes and accolades of his friends and family. He was well-known for his daily walks, where he would chat with just about everyone he met.

Garnet Douglass Baltimore died on June 12, 1946, at the age of 87. He passed away in the family home, where he had grown up and lived for much of his life, still only blocks from a much-expanded RPI. At the time of his death, he was that institution’s oldest alumni. His wife Mary, who had been a tireless worker for women’s suffrage and women’s rights, had already passed on. The couple had no children and they joined his parents and siblings in the family plot in Oakwood Cemetery.

The Troy Record announced his death on the front page. They eulogized him saying, “He was born here, educated here, practiced here, served the public here, died here. He represented Troy: he helped to develop it; he bet on it from birth to death. He was architectural Engineer at Oakwood Cemetery. He laid out Prospect Park. He was probably the greatest surveyor in the city’s history.”

In 1991 RPI established the Garnet D. Baltimore Lecture Series in his honor. The series hosts lectures by prominent African American scientists, engineers and related professionals. Neil DeGrasse Tyson was one of the early guest speakers. 2005 saw Baltimore inducted to the Rensselaer Alumni Hall of Fame. RPI also established the Garnet D. Baltimore Rensselaer Award Scholarship for African American, Hispanic or Native American engineering students with the highest averages in Mathematics and Science. The street where he lived was named for him in 2005, and in 2018, the Garnet Baltimore Hiking Trail, originating in Prospect Park, had its ribbon cutting.

Somehow, Garnet Douglass Baltimore lived a non-racial life during a time of great racial discrimination, even in the North. Described as “tall, handsome and brown-skinned,” he was obviously African American. He seemed to be accepted wherever he went, from his school days, throughout his entire career. No one questioned his credentials or his talent. Even his marriage to a white woman, although noted when they married, was never an issue in his social or business circles.

His name in the newspapers was almost never mentioned in the context of his race, a feat that very few successful black professionals at that time enjoyed. They were always “the colored lawyer,” or “the Negro doctor.” Only once did I find his race mentioned that way in the press. He hobnobbed with the Troy elite, was lauded and welcomed everywhere. He had friends in the notoriously racist Irish wards of Troy, and friends among the rich movers and shakers downtown in the wealthiest parts of the city.

However, this descendant of a proud activist African American family never made racial issues or rights his cause. He must have experienced bigotry during his career. Perhaps not in Troy, where he was well known, but in other areas of the state, and in his travels. He did travel to DC, in 1932, and while there did some survey work for Howard University, perhaps the most well-known historic black college.

That year, he also welcomed John C. Nalle, the son of Charles Nalle, who was dramatically rescued in Troy in difiance of the Fugitive Slave Law. His father, Peter Baltimore, had been involved in that rescue. Other than that, I could find no record of involvement with Troy’s African American community, or with larger African American groups or causes. His descendants and people who knew him said that he only cared about the work before him and that he believed that he could be a friend and colleague to all.

Actually, that’s not a bad legacy.

(GD Baltimore’s layout of one of the sections of Oakwood Cemetery. 1918. Property of Oakwood Cemetery.)

What an interesting life he led. I am sorry he did not have children and grandchildren who could talk more about his personality and give us a glimpse of his thoughts and beliefs.

The point I was making is that we are naming these people in today’s article as “African-Americans” when they did not refer to themselves as that title/ misnomer! These people are Americans! Just like you can’t find any information that he was Indian, you also can’t find anywhere that he’s an African! Not all black people are of African origin is the point! My family roots are from the Americas and we have been miss classified as “Africans” when I talk about native roots I’m not talking about Native American from Asia I’m referring to copper colored American Indians that are black skinned people who’s origins come from the paleo Indian / ancient Mississippians from the south eastern states of America we are a different branch of the tree! Sorry to bother you! I was just making a valid point on his ancestry!