The Great Milk Wars

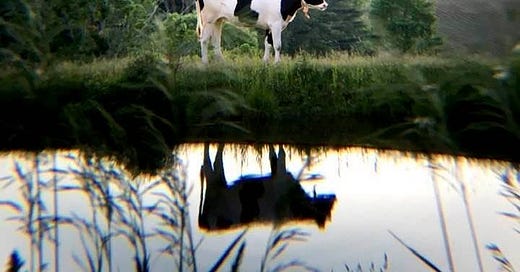

For most of us, our milk has many steps between the cows in the pasture and the milk on our supermarket shelves. Pour a glass of moo juice and grab a cookie and enjoy the story of NY milk.

The longest war fought by New Yorkers in the 19th century was not the Civil War, which lasted a mere four years. It wasn’t the Spanish American War, either, which began in 1898. It was the Milk War, an ongoing conflict pitting business against health, farmers against Big Dairy, bottlers against unions, distributors against each other, and round and round. This war would continue, off and on, for almost fifty years, and still sparks up even now.

So, you milk your cows and send the milk to the market and get paid. What’s the big deal? Would that it was that easy. Our story all begins with swill.

As Brooklyn and Manhattan expanded, it soon became apparent that farmers were not going to be able to house their livestock in our growing and bustling cities. Gone were the days when a farmer could keep his cows in the village green and then deliver fresh milk to his local customers. Pastures would have to be farther and farther out in the rural areas surrounding our cities. While the farmer had more land, he also had a big problem.

This was the age before refrigeration and rapid transportation. The further away from a farmer’s marketplace, the greater the likelihood that the milk could spoil before delivery. The best container for unspoiled milk was the cow, so a plan was devised to deliver feed to city cows, making the field unnecessary. It would inextricably join two great needs in any Western city: the need for milk, and the need for liquor.

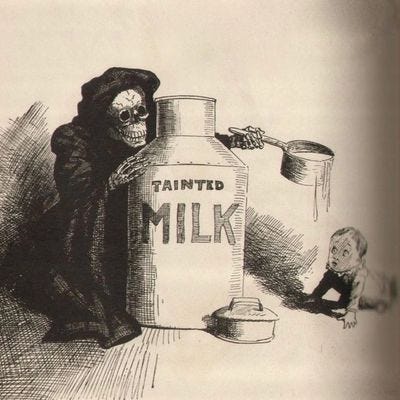

As early as the 1820s and ‘30s, farmers began buying the grain mash left over after whiskey distillers had processed liquor. Distilleries in the city went into the dairy business, and rented stalls to farmers, who would feed this mash to their cows. The mash had a higher caloric count than regular grass, and the cows produced more milk, but they got no exercise and were living in filthy conditions, which produced a thin blue milk, soon known as “swill milk”. Milk wholesalers tried to doctor the milk by adding starch, plaster, chalk, or eggs to make it look thicker and whiter. Plaster? Swill milk was produced in other cities, but nowhere was it more prevalent than in New York City.

An immediate backlash occurred leading to a pure milk movement. By the late 1840’s, scientists were producing evidence showing that this stuff was dangerous to the health of children, leading to death before the age of five for literally half the children in the city, who were dying of tuberculosis, typhoid, or diarrhea-causing bacteria in swill milk. Years later, in 1875, the city enforced a law that prohibited the sale of milk from distillery fed cows, and by the turn of the century, distillery dairies in Manhattan were supposed to be history.

But in 1904, a new health commissioner found that thousands of cows were still being fed distillery slop in NYC. The dairies set up in both Central Park in Manhattan and Prospect Park in Brooklyn were part of the movement to get fresh whole milk to city residents, and both had cows which were put to pasture in the park. The Prospect Park Dairy was torn down in the 1930’s, but Central Park’s Dairy was restored, and is now a visitor’s center.

Doctors and scientists began a movement towards “certified milk”, a term coined by Henry Coit, a scientist working in Newark, NJ, who had lost his own child due to contaminated milk. Teams of doctors would inspect the cows, their feed, their living conditions, their water, and the processes used to handle and transport the milk to market. This was a cumbersome and costly process, so the invention and implementation of pasteurization, as invented by Louis Pasteur in 1862, was a godsend to those desiring to improve the quality of milk. Pasteurization could take place in a factory setting and be both practical and economical. It involved heating milk to kill the germs and bacteria, and then cooling the milk, all without cooking or spoiling it.

Like any new thing aimed at the public, the idea and process of pasteurization needed to be sold to the public. In New York City, Dr. Henry Koplik opened the world’s first dispensary to distribute pasteurized milk and teach mothers about infant hygiene in 1889. Nathan Straus, the owner of Macy’s, “the largest department store in the world,” thought that this clinical method was not effective in reaching the tenements and masses of people throughout the city, so in June of 1893, he opened his first milk depot on the East 3rd Street Pier.

It was a combination laboratory and recreation center, with a small pasteurizing and bottling plant next to a pavilion with tables and chairs. Mothers could come with their children and attend twice weekly lectures on childcare and nutrition, refreshments were available, and doctors were on hand for free examinations. Both adults and children could see the milk being pasteurized and bottled, which was for sale at nominal prices.

The milk depot was a huge success, so much so that Straus opened six more the next year, and by 1906, had seventeen depots throughout the city. He had to have a centralized milk plant to meet the demand, but he knew he could never reach everyone who needed pasteurized milk, so he developed and sold the “Nathan Straus Home Pasteurizer” that could sit on one’s stove. Because of his efforts, many of the women in the tenements of the Lower East Side were pasteurizing milk before many of the local dairies were.

The results were dramatic. Statistics showed the mortality rate among children dropping by half, just because of pasteurization. In 1895 Straus began a nationwide campaign, asking mayors around the nation to allow him to open his milk depots wherever he was invited. By the early 1900’s, depots based on his model were established in many major cities.

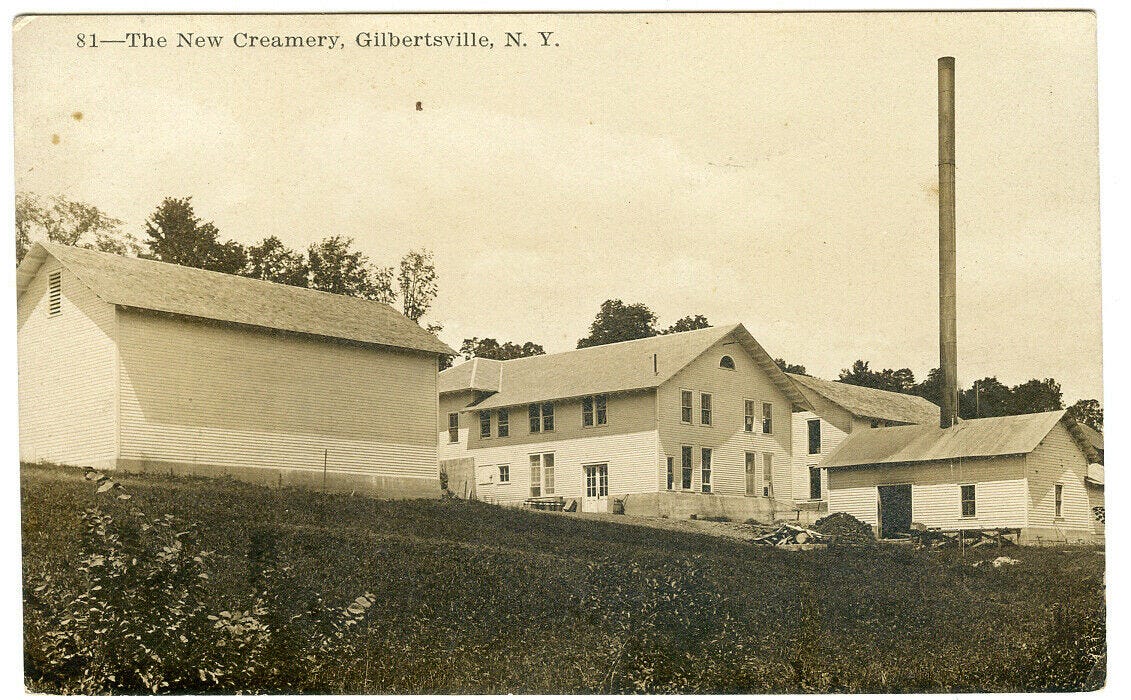

Society ladies took up the pure milk movement, establishing organizations such as the International Pure Milk League, with smaller “Mother’s Clubs”, where women learned how to store and handle food safely, and pure pasteurized milk was dispensed at their meetings. The groups also lobbied to force dairies, milk wholesalers and retailers to abide by sanitation and preparation standards developed by the Department of Health. With their help, and with the backing of city law and vigorous inspection, New York City set the standard for the safest milk supply in the nation. By 1905, all milk traders had to be licensed, and all their suppliers had to agree to inspections of their creameries and farms, no matter where those farms were.

The need for fresh milk and dairy products in this large growing city made the milk business a large and lucrative business. There would be fierce competition among rival companies to be the best, to have the largest customer base, and be the most profitable entity. One of the best ways to make more profit is to lower your costs, and by the 1930’s, the competition among the three largest milk companies was about to come to a head. The three companies were Borden’s Condensed Milk, Sheffield Farms, and U.S. Dairy Company.

We tend to think of milk as a rather genteel and benign kind of business, with happy cows, industrious hayseed farmers and laughing children, but that’s from advertising, not reality. The wholesale milk business was, and is, as cutthroat as the oil business, with the major players vying for millions of dollars.

Sheffield Farms began when a lawyer named L.B. Halsey married Ann Maria Sheffield, and began to take an interest in her family farm. The farm in Mahwah, NJ had carefully bred cows that produced a superior milk, and therefore superior butter.In 1892, he installed the first pasteurizing machine in the US, at his Bloomfield, NJ milk plant. NYC’s own large scale pasteurization programs didn’t take off until 1898, so he was well ahead of popular wisdom.

In 1892, Sheffield Farms merged with T.W. Decker & Sons, an established milk company in business since 1841. Decker had 33 delivery routes and three stores by this time. Thompson Decker was an astute businessman, as well, and is credited as being the first NYC milk dealer to use the railroad to bring his milk into the city from his huge farm in Westchester.

Another very successful milk distributor, Slawson Brothers, under the leadership of Lotus H. Horton, merged with Sheffield and Decker, creating Sheffield Farms-Slawson-Decker, which was eventually called Sheffield Farms, and by 1926 was the largest dairy products company in the world, with almost 2,000 retail routes and over 300 stores, mostly in NYC. Lotus Horton had risen to the post of president of the company, an office he held until his death. Just before he died in 1926, he sold Sheffield to the National Dairy Products Corporation, a company founded in 1923, as a merger of several other dairy firms. Sheffield was their largest holding. They would go on to acquire Breyer Ice Cream in 1926 and Kraft-Phenix Cheese Corporation in 1930. In 1976, National Dairy Products became Kraft.

The U.S. Dairy Company was based in NYC, from at least the 1840’s, and were producers of dairy products, such as butter and cheese. In 1874, after buying the patent, they were the first American company to manufacture margarine, then called oleomargarine. Margarine was invented in 1869 by a French chemist named Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès, who substituted the natural oil butterfat in butter with beef fat oil, which when mixed with milk, would produce a cheaper form of butter. By 1882, the company was producing 50,000 pounds of margarine a day, with over half of that being produced in New York State. That takes a lot of milk.

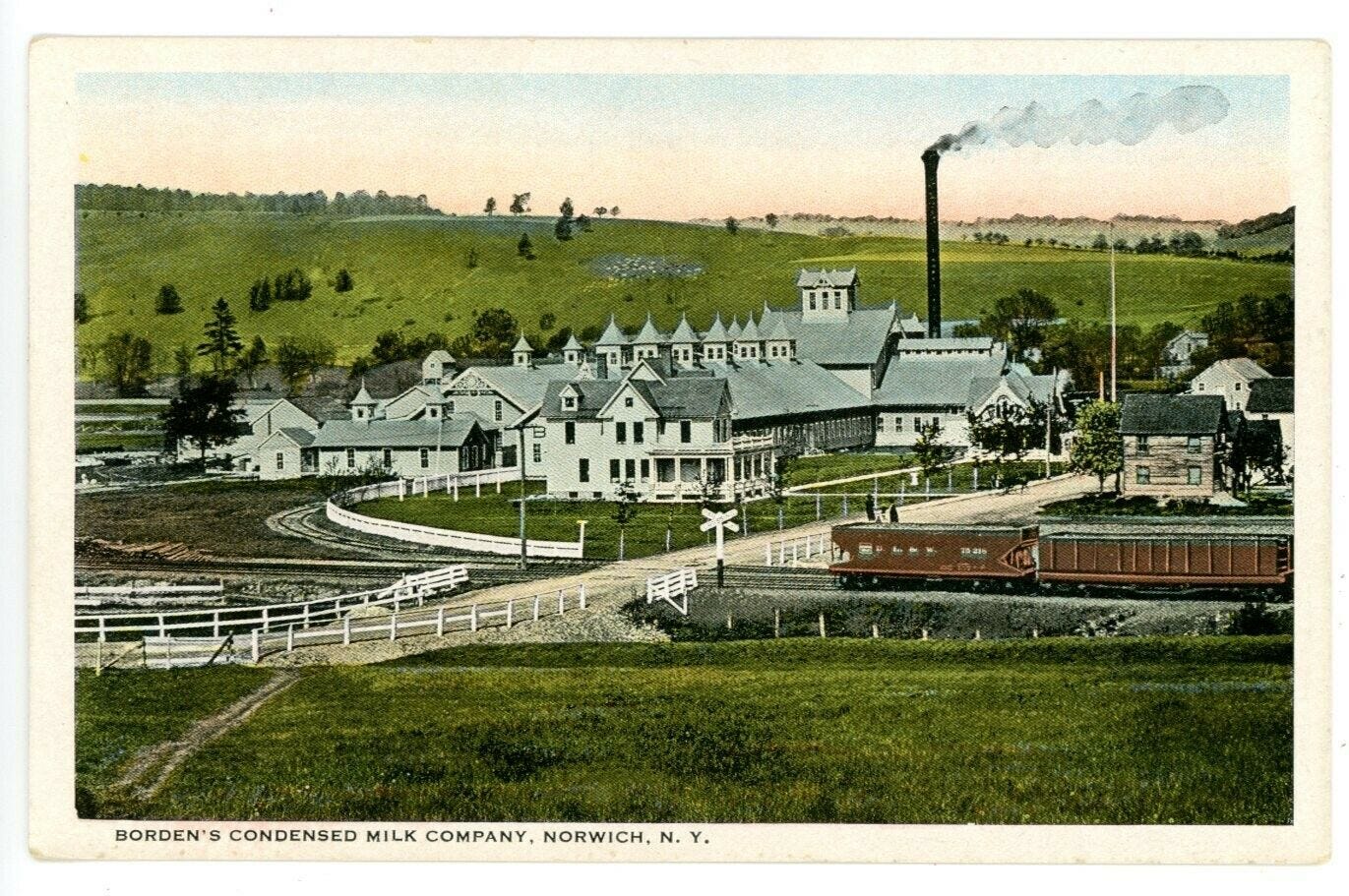

The most famous company in the Big Three was the Borden Company. Borden was founded by Gail Borden, a dairyman from upstate Norwich, NY. Borden was an odd duck who had spent much of his life travelling and holding odd jobs. He had been a newspaperman, a surveyor and a land agent at one time or another. He was also an inventor, credited with the invention of a sail powered wagon, and most famously, the lazy Susan.

He also invented a dried meat biscuit that he hoped could be a staple of long distance plains travel. The biscuit was not the greatest tasting thing, and never caught on, but was recognized as a breakthrough in food, and he was invited to receive a medal at the 1851 London World’s Fair. On his passage back home, he saw several children on board his ship die from drinking contaminated milk. It became his mission to do something about that.

He began experimenting with the vacuum pans used by the Shakers to preserve fruit. He believed the water in milk was causing the spoilage, and by removing it, and canning the milk, it was rendered safe. It was the process of heating the milk and killing the bacteria, the basics of pasteurization, that made the milk safe, but his canned milk was an idea worth pursuing. It wasn’t until he partnered with Jeremiah Milbank, a wholesale grocer, banker and railroad financier, that his business took off.

It was called the New York Condensed Milk Company, and its first ad in 1858 was in the same issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly that swill milk was roundly condemned. The company was soon delivering condensed milk across New York City and Jersey City, NJ. A contract with the U.S. Army for condensed milk assured the company’s success, and they licensed the condensing process to other manufacturers to keep up with orders. After the war, Civil War veterans gave them a new consumer base familiar with the product.

In 1874, Borden died, and his sons took over. They began delivering whole fluid milk in 1875. In 1885, they pioneered the use of glass bottles for milk distribution. In 1899, the company incorporated at the Borden Condensed Milk Corporation, and continued to grow, opening canning facilities, pasteurizing and bottling facilities across NY, NJ and Illinois. World War One gave them further enormous growth and profit, allowing them to go multinational. In 1919, the name was changed to the Borden Company, and by 1930 had acquired more than two hundred companies, becoming the nation’s largest distributor of fluid milk.

“Got Milk?” This may be a catch phrase from a recent dairy industry campaign, but it was a valid question during the 1930’s in New York. Due to factors totally within human control, milk was in short supply to the city at the height of the Great Depression. The “Big Three” dairy companies were locked in a pitched battle for control of the very lucrative NYC milk market. Milk, like most food items, is graded. The highest quality milk, designed for drinking, is called “fluid milk”. Lesser qualities of milk were used for the manufacturing of cheese and butter. Cream was produced naturally by simply skimming it from the top of the milk.

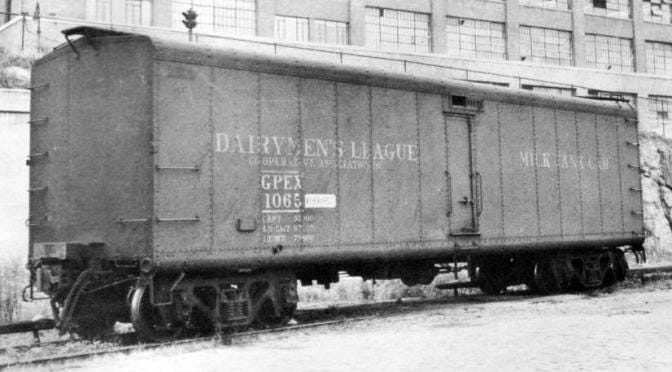

By the 1930’s, milk was the second largest perishable product coming into NYC. Special milk trains, railroad cars carrying nothing but milk, came into the city every day. The New York Central Railroad had a monopoly on Manhattan freight, and its milk trains came into Manhattanville, that part of what is now Harlem, located near 125th Street and the Hudson River. The New York and New Haven Railroad milk trains went into the Bronx and Long Island, and other railroads unloaded milk at the New Jersey waterfront, where the milk was immediately shipped on barges or ferries to bottling plants in the boroughs and the city. By 1933, there were 12 pasteurizing plants in Manhattan, 2 in the Bronx, and 15 in Brooklyn. Only a few of these buildings still stand.

The 1930’s were hard times, as the decade struggled with the Great Depression. Milk was a national commodity, and problems with pricing and fair wages were not confined to NY State. There were “milk wars” in Iowa, in Illinois, Kansas, and throughout the Farm and Corn Belt of the Midwest. The cities of Houston, St. Louis, Atlanta and Chicago all had conflicts between farmers, milk dealers and large bottlers. But New York, as usual, went the extra mile.

In the early 1930’s, in New York City, an increased demand for milk was met with a lowering of prices. More milk was needed, but dealers wanted to pay less for it. In 1933, the state legislature ordered a study of the collapse of the milk market. The study was led by Watertown state senator Perley Pitcher, and his committee soon concluded that New York City’s cutthroat milk business had far reaching implications. Competition had been one of the major factors in pricing, with the Big Three undercutting each other to dominate the lucrative milk market share. The middlemen, the milk dealers, took the brunt of the cuts, and they, in turn passed that along to the dairy farmers, resulting in the lowest prices in years. So low that the farmers were not even making costs and were losing money and losing their farms.

Both Borden and Sheffield Farms struck independent deals with their milk suppliers and had their own milk cooperatives. Borden’s had a long-standing deal with the Dairymen's League Cooperative Association (DLCA). The DLCA had its own processing plants and had 60,000 of the 80,000 dairy farmers in the upstate milkshed under contract. They promised to not compete with Borden in NYC, and Borden promised to only buy milk from them.

Sheffield Farms had a similar arrangement with their own dairymen, organized under the Sheffield Producers Cooperative Association, which had over 16,000 member farmers. These two groups guaranteed the member farmers a market for their milk, as well as a balance in the pricing of fluid milk and manufacturing, or Grade II, milk. Of course, that also tied them to any agreements or demands made by Borden and Sheffield Farms. Outside of these two groups, there were about 10,000 independent farmers who sold to smaller milk companies and cheese makers. These farmers suffered the most in the wheeling and dealing of the milk business, as they didn’t have the protection of the larger co-ops.

In 1938, in the midst of the Great Depression, the battle over milk was raging throughout the country. In New York City, the Big Three sold two-thirds of all the fluid milk in the entire city. These companies competed fiercely with each other but were united in constituting a virtual monopoly on the city’s milk supply. New York was their town. Consequently, they were able to dictate prices, and in the mid-1930’s, cut the prices they were paying their suppliers, the farmers of New York State.

At a time when farmers needed money the most, the Big Three were making it impossible for many of the farmers to break even, forget making a profit. Family farms, passed down for generations were being lost. The farmers weren’t going to take it anymore, and began organizing in earnest, to demand fair prices for their milk. It was going to get ugly, and unpleasant, and the threat of New York going without milk was real.

In February of 1939, the federal courts overturned the New Deal regulatory pricing system for milk in the New York milkshed. This system was designed to guarantee a steady price for NY milk and set in place collective bargaining agencies that negotiated prices between producers and wholesalers. With this law tossed out, the Big Three immediately slashed the prices they would pay for milk, leaving farmers in the hole, once again.

The Supreme Court would later that year reinstate the system, but the price drop, coupled with a summer drought upstate, had a devastating effect on farmers, and they were angry. Farmers in the northern counties called for a strike and were soon joined by farmers across the state. The hive had been stirred up, and this time, the 1939 milk strike promised to have lasting effects on New York’s milk industry.

An upstate dairy farmer named Archie Wright had organized his neighbors into the Dairy Farmers Union of the State of NY, known as the DFU. In 1937, they had shown the Big Three that they could organize efficiently and well, and succeeded in closing down Sheffield Farms’s largest upstate plant, in Canton, for 108 days. Because the strike was peaceful, and the milk was not spilled out onto the road, but taken to other independent plants, especially important at a time when people were starving, the strikers were beginning to win the hearts and minds of the people, as public opinion turned away from the milk companies, and towards the farmers.

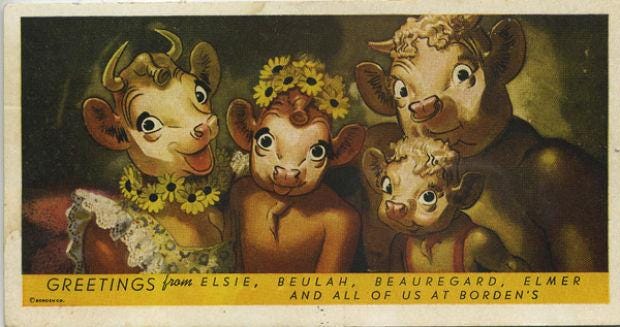

Borden was the biggest of the Big Three. They realized that they needed to win back the goodwill of the consumer, and what better way to do that than adopt a friendly and genial mascot? They came up with Elsie the cow. The entire country would soon know Elsie, a bright-eyed cartoon bovine of the Jersey variety with a curl between her horns, a chain of daisies around her neck, and a frilly apron around her, um… waist. She began appearing in Borden’s ads in 1938, designed to give the company a warm and comforting image. Elsie began to get fan mail and was soon made Borden’s official “spokescow.”

Borden’s had an exhibit in the 1939 World’s Fair, held in NYC. Part of their exhibit consisted of a herd of cows that was milked twice a day. People asked which cow was Elsie, so they picked a pretty candidate who was officially re-named Elsie, and moved her to her own private “boudoir” with pretty milkmaids to take care of her, a four-poster bed and straw mattress, curtains, and a giant telephone, so Elsie could call “the office”. The bemused cow never knew she won the lottery. They also decided she needed a family, so they brought in her “husband”, a bull named Elmer. His boudoir had a poker table so he could have a night with the boys. Soon after, Elsie and Elmer had a “daughter”, named Beulah. All this took place during the World’s Fair.

The public ate it up, and Borden’s, pardon the pun, milked it for all it was worth, even sending Elsie to Hollywood to co-star in the movie Little Men, with actress Kay Francis. After the fair closed in 1940, Elsie and Beulah went on a country-wide tour, first by train, and then by a special truck called the “Cowdillac.” Alas, it didn’t last long. In 1941, while Elsie was scheduled to do a Shubert Alley Theater appearance, someone smashed their car into the back of the Cowdillac, injuring Elsie, and she had to be put to sleep. She’s buried on Borden’s farm, in Plainsboro, NJ, which is now a housing development.

Borden’s immediately got another cow to become Elsie, and she continued to be the spokescow throughout World War II, with other Elsies carrying the torch until the early 1970’s. She and Elmer had lots of children, names that are long forgotten. Ironically, Elmer, who never contributed an ounce of milk in his life, outlasted Elsie, and is still the image, and the name of Elmer’s glue.

However, in 1939, while Elsie was baking cookies to serve with milk, the farmers of upstate NY were gearing up for the largest strike in milk history. While Elsie and Elmer were cute, they couldn’t distract from the real financial issues facing farmers and milk manufacturers. Archie Wright was a very good organizer and had learned the art of non-violent passive resistance well. The milk companies couldn’t paint him and his fellow members of the DFU as violent rabble-rousers, so they branded them the next best thing: Communist rabble-rousers.

In August of 1939, after meetings coordinating all of the state’s chapters of the DFU, a strike was called, with special attention paid to the U.S. Dairy plant in Canton, located in the St. Lawrence Valley, and the nearby Sheffield plant at Heuvelton, both plants closer to Canada than New York City. Over a third of NYC’s milk came from these two plants. Heuvelton was Archie Wright’s home town. With minimal violence, the strike was successful, stopping the flow of milk to NYC, the largest market in the country.

For the first time, women played an important role in these strikes, as they picked up the slack from striking men, some running the farms and doing all the chores in their men’s absence. Cows and other farm animals don’t care if you are on strike, and need to be milked, fed and taken to and from, pasture. Women also were on the picket line, subject to the same abuse as men, which drew the farmers even closer together, and more determined to succeed.

The DFU’s success helped change the stereotype, especially in the cities, that farmers were ignorant, clod-hopping hicks. Their sophisticated resistance tactics and their success in seriously affecting the large and powerful milk companies had its desired results. By the third day of the strike, 60% of the milk deliveries to NYC had been stopped, and the Big Three had to negotiate. New York City’s mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia, invited the DFU leadership and the Big Three to New York to broker a deal.

Nine days after the strike began a new deal was struck, with the farmers receiving a 45% increase over what they had earned before the strike. It was a tremendous victory for the Dairy Farmers Union. The farmers upstate celebrated with parades and marching bands. But they were a bit premature. Elsie’s parent company and its cohorts were about to drop some big cow patties on their victory.

No sooner had the ink dried on LaGuardia’s agreement, than the Big Three decided to ignore it. Instead, they launched a massive smear campaign on Wright and the leadership of the DFU, branding them as subversive Communists. Although he vociferously denied any Communist ties or membership, the campaign against him was so powerful that it split the DFU into factions, with many members calling for Wright’s head. Elections were held, and Wright’s opponents, who peppered the voting convention with flyers and signs reading “"Mr. Wright Denies It, But Communism Is In Dairy Farmers Union," and "Who Is the Rubber Stamp For the Communist Party Inside the Dairy Farmers Union?"

Wright lost, big time, and the leadership of the DFU went to those who were paid off by the Big Three. The Dairy Farmers Union would never again be able to organize as well, or command the attention of the milk producers, or the public, as it had done in the Milk War of ’39. New pricing structures were established, higher than before the strike, but not as high as what Wright had negotiated. Life went on, and soon, World War II changed everything.

In New York City, the Big Three were changing from horse drawn milk wagons to motorized trucks. Their huge stables in Manhattanville, near the train station, would become obsolete. In 1938, Sheffield Farms built the largest milk depot and distribution plant in the world, on W. 57th Street. Trucks could take milk to all corners of Manhattan more cheaply and faster than horse drawn wagons. The milk industry was modernizing, at the same time they were being threatened upstate. After regaining control when the Milk Wars and World War II was over, all of the Big Three’s plants moved outside of the city.

The Manhattanville stables were sold to Columbia University. CBS would eventually buy the W. 57th St. plant, and it is still the location of their broadcast studios. The plants in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens still operated for many years, but the milk business was changing from home delivery and stand-alone milk stores to supermarkets. 75% of their business had been home delivery. By the 1960’s, that number was reduced to only 25% and soon became a nostalgic memory. Other milk products, especially ice cream, began to become more important than milk. Today’s milk wars are not between farmers and monopolies but now are about the desirability of “raw” milk, plant-based milk substitutes and non-fat milk. Elsie would be heartbroken.

Source materials: “Manhattanville and NY’s milk supplies” by Mary Habstritt; “Elsie the cow’s rise to stardom” by Sam Moore, and “The 1939 Dairy Farmers Union Strike” by Thomas J. Kriger, the New York Times, and Forgotten New York.

Well researched and beautifully written! Reminds me of my hometown and family roots in upstate NY. My maternal grandmother’s family went generations back in dairy farming (Halberts), and my paternal great grandfather and my father worked for the Dairyman’s League depot in Mt Upton (Robinson).